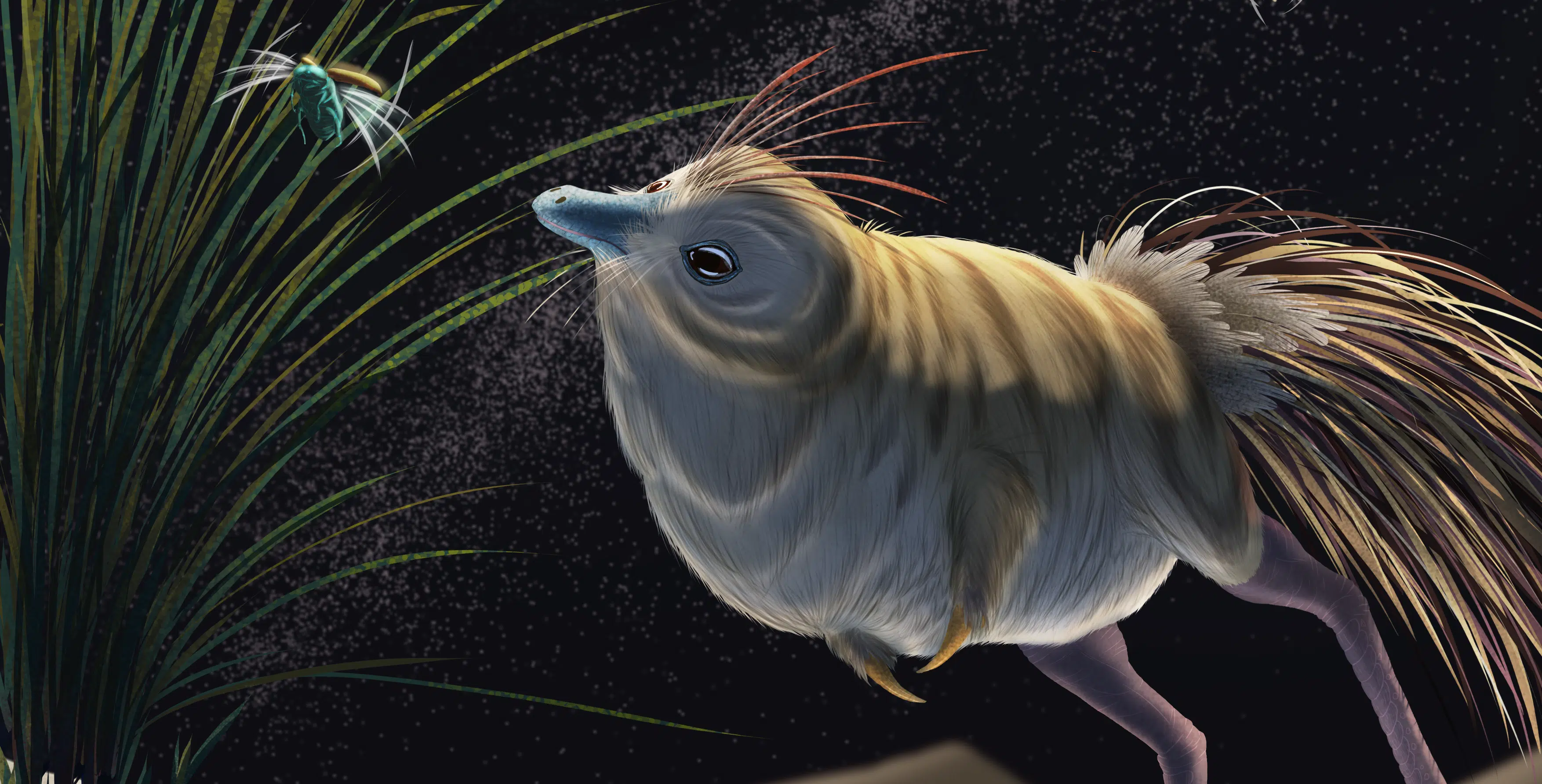

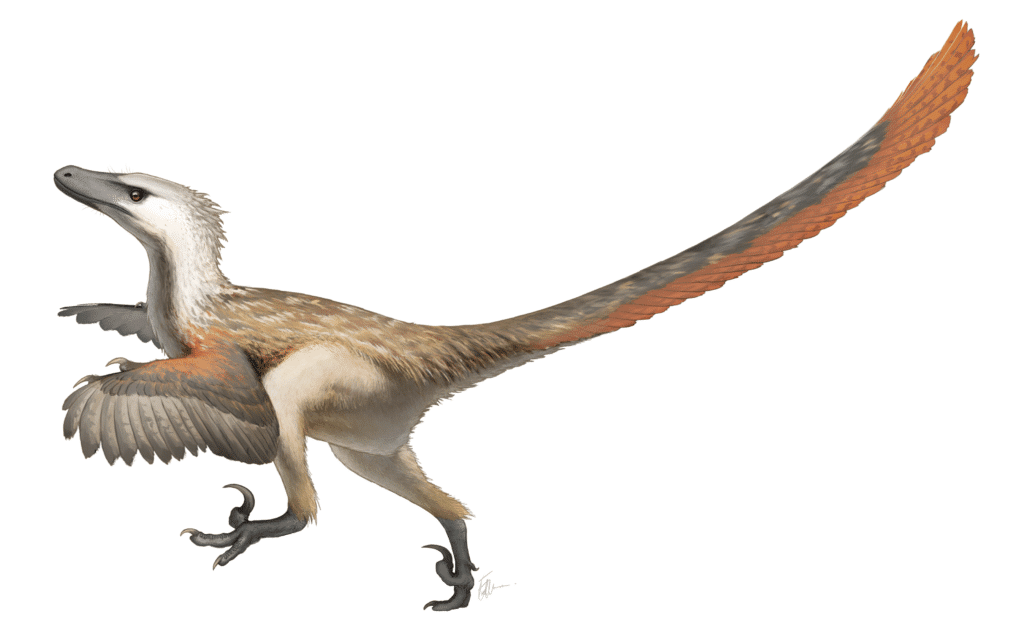

Roger Benson’s latest paper features a feathered, chicken-sized, bird-like dinosaur revealed to have the hearing ability to rival a barn owl – a specialised nocturnal predator. Combined with short, muscular arms ending in a single giant claw for digging, Shuvuuia deserti (meaning ‘desert bird’) is not what you might classically expect from a dinosaur. Such are the revelations from fossil discoveries in recent decades that are changing how we see birds today. Professor of Palaeobiology at the University of Oxford, Roger researches the evolution of dinosaurs – including bird origins – and large-scale evolutionary patterns. He explains why ‘dinosaur’ is more ‘incredible bird’ than ‘terrible lizard’…

Are birds really dinosaurs? Is it disputed?

There’s no longer really any doubt that birds are a type of dinosaur. These days, the debate is about details. The strong evidence doesn’t just come from fossilised bones and similarities found across the skeleton, but from fossilised soft tissue – especially feathers. Many dinosaurs had not just some kind of body covering, but distinctive bird-like feathers. Rare fossils also give us glimpses of the behaviour of bird-like dinosaurs, such as Mei long, a small, duck-sized bipedal dinosaur from the Cretaceous era. It was found preserved in volcanic ash falls – a bit like Pompeii – captured curled up in a sleeping position very similar to how a lot of birds roost today.

If feathers evolved in dinosaurs, what is the origin of birds?

Birds belong to the theropod group of dinosaurs that included T. rex. Theropods are all bipedal and some of them share more bird-like features than others. Archaeopteryx, discovered in 1861, was for a long time the only truly bird-like dinosaur – it’s from the Late Jurassic era (150 million years ago). Others closely related to birds, like Velociraptor, can be from the Late Cretaceous (100-66 million years ago), so they’d also had a lot of time to evolve independently. It’s the Late Jurassic where we start finding really interesting, distinctive, bird-like dinosaurs – especially with recent fossils from China preserved in fine-grain sediments from lake beds.

Such as?

Anchiornis is a Late Jurassic winged dinosaur, with large feather arrays on its legs. Fossils like this suggest the intriguing possibility that birds evolved from a gliding ancestor that had effectively four wings. That is cool. Also, Yi qi was discovered in the last couple of years. Its fossil has preserved soft tissue with a bat-like wing membrane.

Could they fly?

Not all of the dinosaurian close relatives of birds could fly. But those that could, flew in a range of different ways – suggesting early evolutionary experiments of flight, with birds being the most successful of those experiments, and persisting to the present.

Were the Velociraptors in Jurassic Park covered in feathers?

We can confidently think of Velociraptor as having a bird-like feather covering, even though its fossils only preserve the bones. The skeleton has quill knobs on the ulna (wing bone – also found on today’s birds). Close relatives are better-preserved and show a complete body covering, ranging from down to quill feathers. They couldn’t fly, so the feathers could be to do with display. Reconstructions have moved on a bit since Jurassic Park… Artists have only recently let go of scaly, reptilian-like depictions. We can think of dinosaurs as more bird-like than reptile-like.

Above: an artist’s interpretation of Shuvuuia deserti, which means ‘desert bird’

© Viktor Radermacher

Were they warm-blooded?

For dinosaurs closest to birds – or, in fact, dinosaurs in general – we have so much evidence that suggests they were warm-blooded, short of actually sticking a thermometer in one. Growth rates and insulation are the smoking gun. They grow fast – we know from cutting up bones – faster than reptiles (including those from the same period), but not quite as fast as modern birds or mammals. For theropods where we can see soft tissue, we can see insulating feathers. All dinosaurs were on the road to becoming warm-blooded, with steps towards faster metabolic rates and very high body temperatures somewhat after the origin of birds. There wouldn’t have been a sluggish T. rex waiting for prey to walk by; we should think of them as active, curious animals.

What would you say to people that would say birds aren’t dinosaurs?

If birds aren’t dinosaurs, then we have no idea what they are. Birds share so many features with theropods and there are no other candidate fossil groups. When you understand that birds are a type of dinosaur, that the evidence has stacked up, everything starts to make more sense. Birds inherit their bipedalism from theropods, explaining why they evolved flight using just their forelimbs, unlike bats or pterosaurs. If that hypothesis was wrong, we’d expect to be just as uncertain about bird origins today as 30 years ago.

But didn’t Triceratops, from a completely distant group of dinosaurs, have a beak?

Many groups have lost teeth and evolved a beak. Triceratops had a beak at the front of the mouth. Sheep also lack teeth at the front in their upper jaw. That’s for grabbing vegetation, and evolves frequently.

Is flight the key to the origin of birds, then?

Palaeontologists ask ‘what makes Archaeopteryx a fossil bird rather than another bird-like dinosaur?’, and it’s the capability of powered flight. The wing feather arrangement is much more similar to modern birds. But the more we know about bird-like dinosaurs, the more we find that specific features of birds have an older origin. Walking on two legs, having feathers, laying eggs, warm bloodedness – they’re just inherited features from dinosaurs.

How did powered flight begin in bird-like dinosaurs?

Not everyone agrees, but many think they were tree-climbing animals that glided. I think they evolved flight from the trees down. From an aerodynamic perspective it’s easier to see how that would work. To evolve flight from the ground up, evolution would need to master a number of different things about flight control and power quickly. That’s more difficult. When did they learn to climb trees? We would like to know!

“There wouldn’t have been a sluggish T. rex waiting for prey to walk by; we should think of them as active, curious animals.”Professor Roger Benson

Why were birds the only dinosaurs that survived the mass extinction at the end of Cretaceous?

We know from the fossil record that large-bodied land animals were hit hard. Only the tiny survived. The smallest dinosaurs weighed about 500 g, but to survive as a land mammal you needed to weigh less than 50 g, and even then the chances were very slim. Lots of bird groups also went extinct. All sorts of reasons have been suggested – such as being a seed-eater or fish-eater (after the 10-km diameter meteor struck, there was a lack of sunlight due to dust, and freshwater ecosystems were a refuge). Some places would have been less terrible than others – clearly proximity to the impact zone in Mexico would have been terrible – but there were global effects.

Will only small animals survive the current sixth mass extinction and the bird declines BirdLife scientists are monitoring today?

We know from the fossil record that mass extinctions happen, but each one has a different cause and pattern. So we can’t predict what will happen next based on past mass extinctions. It’s much better to look at what’s happening to birds and other animals right now. The extinction of the dinosaurs is the most abrupt – it could have happened in a single year. The current mass extinction seems a lot faster than some of the other mass extinction events, though, in terms of rate of decline of abundance and rate of species loss. It’s terrifying, but only if it continues. And we have some control of this if people take action.

The other lesson from mass extinctions is that the biosphere will recover. But not in our lifetimes – only on timescales that aren’t useful for human society. Some of our best fossil record studies monitor extinctions with data points every 100,000 years … So today, monitoring birds is one of the most important things we can do to catch species before they’re unknowingly lost.

Favourite bird?

I really like the Inaccessible Island Rail, the smallest flightless bird, living precariously on a tiny island. How can it be so small? It’s got something to tell us about evolution. No dinosaur had ever been that small. Islands are fascinating for an evolutionary biologist and we can’t risk losing this information from science, the sum of human knowledge. That’s just one reason why BirdLife’s work to protect island birds from introduced species is so important.

Given your expertise, how do you feel when you look at birds today?

I like watching them because I like animals and birds are some of the most visible. You can say that a pigeon’s foot is similar to a dinosaur’s – birds have inherited so much from dinosaurs but are also so distinctive in their own right. I respect that and see them doing something fundamentally different to what most dinosaurs would have done. They use resources in a way that ground-walking animals can’t. At any one time there were probably only about 1,000 species of dinosaur on earth, whereas birds have taken what they’ve inherited from dinosaurs and done a lot more with it, giving rise to an enormous diversity of 11,000 species. People love dinosaurs and people love birds. What could be more interesting?

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

Colombia, Paraguay, Brasil y Argentina potenciarán la protección y restauración de sus pastizales naturales gracias al aporte financiero de BirdLife Américas.

Los Pastizales naturales del América del Sur son un bioma imponente compuesto principalmente por un manto ondulado de vegetación herbácea. Conocidos también como llanuras, llanos o pampas, los pastizales proveen servicios ecosistémicos esenciales para la vida como: la purificación y recarga de fuentes de agua, provisionamiento de fibras, alimentos y combustibles, almacenamiento de carbono, y regulación del clima. Además, son el hogar de una exuberante variedad de vida silvestre y cuentan con una gran riqueza cultural, espiritual y recreativa.

Más de 600 aves autóctonas y miles de aves migratorias dependen de este frágil y amenazado ecosistema. Desafortunadamente, la intensificación y expansión de prácticas humanas mal-manejadas como: la agricultura, la ganadería, el desarrollo urbano y el uso indiscriminado del fuego han mermado drásticamente su extensión y salud.

Para afrontar esta problemática, en 2006 BirdLife lideró la conformación de la Alianza del Pastizal con el apoyo de sus socios: Aves Argentinas, SAVE Brasil, Guyra Paraguay y Aves Uruguay. Desde entonces, más de 560 mil hectáreas de pastizales del Cono Sur se encuentran manejadas con prácticas de pastoreo responsables que combinan su conservación con la producción sostenible. A la par, en Colombia, la Asociación Calidris en asociación con otras 12 organizaciones conforman la Alianza Sabana, quienes se enfocan en la implementación de soluciones innovadoras de conservación para los Llanos colombianos.

A pesar de los grandes logros alcanzados hasta el momento, todavía existen varios desafíos por afrontar. Precisamente, para potenciar las acciones de conservación y restauración de este ecosistema, BirdLife Américas lanzó a inicios de noviembre de 2021 un Programa de Pequeñas Donaciones para la Conservación de Pastizales Naturales. Se trata de fondos semilla para incentivar proyectos de conservación y/o investigación que contribuyan durante un año a la conservación de los pastizales naturales en la región y las aves terrestres, playeras y acuáticas asociadas a éstos.

El Programa de Pequeñas Donaciones para la Conservación de Pastizales Naturales es una iniciativa de BirdLife Américas que otorga fondos semilla para incentivar proyectos de conservación y/o investigación en la región que contribuyan a la preservación de estos ecosistemas y sus aves.

Conoce a los seis proyectos ganadores

La miel de la biodiversidad: identidad gastronómica para la conservación de las sabanas inundables

Con el respaldo de: Asociación Calidris

Equipo técnico: Ocampos Andrea Barrera, Nelsy Niño, Beatriz Ramírez, Marcela Vega, Natalia Roa.

Con un enfoque participativo y de género, este proyecto potenciará la conservación de las sabanas inundables de Colombia, en Reservas de la Vereda Altagracia (un Área Importante para la Conservación de las Aves – IBAs, por sus siglas en ingles). La idea es empoderar y educar a una comunidad de mujeres para que aprovechen, de forma sostenible, su entorno y biodiversidad en su gastronomía. El proyecto abarca estrategias de conservación y restauración para garantizar el alimento, los materiales y el espacio de anidación necesarios para la abeja mansita (Melipona favosa), la tecnificación para producir miel de forma eficiente y limpia, la difusión del valor agradado de este producto y la integración con la red de productores de meliponicultores de Casanare. De esta forma, se pretende contribuir la soberanía alimentaria, la resiliencia frente al cambio climático y conservación de la vida silvestre asociada a estos llanos.

Estudio de la dinámica de carbono en diferentes sitios ecológicos y tipos de manejo en establecimientos ganaderos en pastizales naturales de Paraguay

Con el respaldo de: Guyra Paraguay

Equipo técnico: Diego Ocampos

Se investigará varios aspectos relacionados con la dinámica de carbono en el suelo y las plantas. Se estimará la captación de carbono, composición botánica y caracterización de nutrientes en pastizales naturales de acuerdo con variables de conservación de biodiversidad y suelos, así como las características ecosistémicas presentes en establecimientos ganaderos y los tipos de pastoreo realizados. De esta forma, se identificarán buenas prácticas de manejo pastoril que permitan contribuir con evidencia científica a la protección y producción sustentable en pastizales como una estrategia de conservación de la biodiversidad y mitigación frente al cambio climático. Esta iniciativa se desarrollará en al menos tres establecimientos ganaderos ubicados en los departamentos de Caazapá y Paraguari; que basan su producción en pastizales naturales.

Optimización de la restauración ecológica de campos en Pampa con recolección mecanizada de semillas de especies nativas

Con el respaldo de: SAVE Brasil

Equipo técnico: Rodrigo Dutra da Silva, Sandra Cristina Müller.

A partir de una referencia existente en el mercado, se construirá una maquina recolectora de semillas maduras por contacto, práctica, liviana y accesible, que permitirá fortalecer la capacidad y conocimiento para realizar acciones de restauración ecológica en los campos nativos de la Pampa brasileña. A través de este proyecto piloto, se buscará solucionar la falta de semillas de especies herbáceas nativas para la siembra directa en territorio que existe actualmente en el mercado; lo cual constituye un gran problema en la cadena productiva entre la cosecha y la siembra. Además, gracias a la cosecha mecanizada, se pretende potenciar y optimizar las intervenciones a gran escala para recuperar extensas áreas degradadas. Cerca de 95 especies de aves silvestres dependen de la conservación de estos pastizales Sulinos.

Uso de nuevas tecnologías para el monitoreo de buenas prácticas de manejo de pastizales y conservación de aves de pastizal amenazadas en la provincia de Corrientes, Argentina

Con el respaldo de: Aves Argentinas

Equipo técnico: Adrián Di Giacomo, Melanie Browne, Florencia Pucheta, Yamila Barasch.

Este proyecto diseñará una herramienta de programación que combina sensores remotos con el conocimiento sobre la biología de aves amenazadas para evaluar si en los campos con pastizales se aplican o no buenas prácticas para la conservación de aves. Es decir, un instrumento de gestión para el monitoreo de impacto, análisis de datos y la toma de decisiones basado en la plataforma Google Earth Engine (GEE). Se prevé la capacitación de actores locales para que puedan utilizar esta herramienta en la gestión adecuada de su territorio.

Uso de Conservación y manejo de la Loica Pampeana

(LLeistes defilippii)

Con el respaldo de: Aves Argentinas

Equipo técnico: Candelaria Neyra, Igor Berkunsky, Clara Trofino, Gerónimo Peralta Martínez, Pablo Grilli, M. Gimena Pizzarello.

Consiste en la generación de un programa de conservación a largo plazo para evitar la extinción de la Loica Pampeana (Leistes defilippii); una de las dos especies más amenazadas en los pastizales de Argentina. Para ello, se realizarán monitoreos bióticos y se establecerán redes locales conformadas por productores ganaderos, académicos, gestores ambientales y naturalistas, con quienes se promoverá un sistema participativo de generación y uso de la información a través de plataformas de ciencia ciudadana.

Manejo con remoción de invasoras y pastoreo para restauración de pastizales serranos de la región Pampas de Argentina invadidos por Acacia melanoxilon: diversidad de aves y stocks de C como indicadores de la recuperación

Con el respaldo de: Aves Argentinas

Equipo técnico: Juan Pablo Isacch, Esteban González-Zugasti, Facundo Pedraz, Paulina Martinetto, Augusto Cardoni, Gastón Morán, Pamela Rivadeneira, Tomás O’Connor, Stella Román y Sofía Martin-Sirito.

A través de esta propuesta, se busca valorar cómo se recupera el pastizal natural serrano, luego de la remoción de la Acacia negra (una especie exótica e invasiva) y la implementación de un manejo agro-pastoril adecuado. Los investigadores involucrados monitorearán constantemente cómo varia la diversidad de aves, los stocks y dinámica de carbono, así como la aparición de Acacia negra y pastizal nativo, como indicadores de cambio en el sitio de estudio: la Estancia Paititi, Sistema Serrano de Tandilia. Finalmente, también se evaluará la viabilidad de diferentes opciones que otorguen una sostenibilidad económica a la remoción de la acacia.

Un agradecimiento especial para Bruce Peterjohn y Charles Duncan por su generoso apoyo en el proceso de selección de las propuestas.

Mirea Peris

In the past, naturalists thought that birds had small brains only capable of simple processes. But today, the expression ‘bird brain’ is no longer a disparaging descriptor. Author of the New York Times best-seller The Genius of Birds, Jennifer Ackerman shines a light on the nature of animal intelligence through birds in her latest book, The Bird Way. Combining modern research with personal experience, she gives us a new look at how birds play, talk, parent, work and think, showing us that they are capable of activities we once considered unique to our own kind – such as manipulation, altruism or communication among species – and proving that our avian friends are far more complex than we ever imagined. As prominent biologist E. O. Wilson said: “When you have seen one bird, you have not seen them all.”

You’ve been writing about science and nature for many years, from the human body to oceans – why did you decide to pick birds’ brains?

As a bird lover and science writer, I am an avid reader of scientific journals. Recently, I started noticing an abundance of new research on birds’ behaviour, and saw that our understanding of birds was shifting. I’ve been a birdwatching enthusiast since I was a kid – I used to think: “What is going on in their minds when they are going about their daily lives?” – so the whole idea of birds being more intelligent than we thought fascinates me. I always believed birds were very resourceful, but writing these books has been revealing! How can a tiny brain have such an extraordinary capacity?

Why use expressions like ‘the bird way’ or ‘genius’, and not just ‘intelligence’?

I like ‘genius’ because, in my understanding, the word includes not only exceptional abilities but also the ‘genius’ of evolution: how adaptation creates extraordinary skills to find solutions. A few years ago, I got intrigued by the quote “There is a mammal’s way and there is a bird’s way,” and understanding what it meant. Birds have these remarkable mental capacities because they have had to solve difficult ecological and social problems – just as we have. I hope the title of my latest book raises the question: “Do birds actually have a ‘way’ of being in the world?”, and motivates people to learn more about these feathered masterminds.

Above: Corvids are well known for their intelligence but notably lack a neocortex – found in the brains of ‘clever’ primates. However, says Ackerman: “New findings show that birds do, in fact, have a brain structure comparable to the neocortex, though it takes a different shape.” © Philip Openshaw / Shutterstock

“The way we understand other creatures is currently changing, and the unexpected capabilities and behaviours of birds have been a key part of this progress.”Jennifer Ackerman

Humans sometimes tend to anthropomorphise other creatures in an attempt to understand their behaviours. How do you overcome this instinct?

The idea of attributing to non-human species mental qualities we consider unique to humans is very controversial… My job is to be a translator of ‘hard science’ and make it both engaging and accurate. I think the way we understand other creatures is currently changing, and birds have been a key part of this progress.

Through research, scientists are observing unsuspected capabilities and behaviours we thought unique to humans. For example, members of the corvid family were documented playing in the snow for pleasure and assembling complex tools that a 3-4 year old child could not; and lyrebirds were observed learning other species’ calls to fool their own kind. Some birds, such as Japanese Tits, may even use grammatical rules to decode combinations of alarm calls, while Pied Babblers have alarm calls that appear to encode messages that go beyond the meaning of their individual parts – both interesting parallels with human language. So I would say it is not anthropomorphism, but scientific observation and research.

In your book you explain amazing behaviours from many different bird species. Which is your favourite?

This is such a difficult question! I used to answer chickadees, as I have always been amazed by their complex communication skills, but the bird I fell in love with while writing The Bird Way was the Kea. These birds are so child-like – smart and exploratory – and they even have a ‘play-call’ that elicits them to play and chase each other, which is quite an amusing thing to watch.

One of the problems with humans abusing nature is that we consider ourselves to be ‘higher’ than other species. With your perspective on avian intelligence, what do you make of this?

Birds show there are different ways to wire a smart brain. Their behaviour helps us realise we are not as unique as we thought. Rachel Carson wrote: “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders of life around us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.” More than ever, birds are threatened by habitat destruction and climate change. We must work to ensure we have the chance to learn more from them (and other species) in the future. I hope my books promote an appreciation for birds as the innovative and thoughtful creatures they are. Maybe, by better understanding the intelligence of other non-human species, we will treat nature with the respect it deserves.

Find out more at jenniferackermanauthor.com

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

By Jessica Law

Header Image: The Olm is nicknamed the ‘human fish’ due to its fleshy skin colour. Another ‘human fish’, Dušan Jelić discovered 200 Olms on one cave dive © Vedran Jalžić

Read the article in Serbo-Croatian here – Članak na srpsko-hrvatskom jeziku pročitajte ovdje

Pale and slender with fine, fringed gills, you could be forgiven for thinking that the Olm Proteus anguinus came from another world entirely. And in a way, you’d be right. This rare freshwater salamander is eyeless, devoid of pigment and possesses only the smallest, most delicate of limbs. To us humans, it can seem like there is something missing. But in reality, it is perfectly adapted for life in subterranean caves beneath the Dinarides mountains in the Balkans, Europe. In fact, the Olm is found nowhere else on earth. With a heightened sense of smell and hearing, the ability to resist long-term starvation and even a newly discovered sensory organ that detects the electric fields of other animals, it has everything it needs to survive in this secluded environment.

Like its occupants, the limestone caves of the Dinarides are truly exceptional. In some places, vast stalactites and stalagmites create stunning, cathedral-like formations, while other areas preserve fossils from former millennia. This is the location where naturalists discovered cave-dwelling animals for the first time, creating a whole new branch of biology. The Olm and its fellow cave-dwellers may be perfectly suited to life underground here, but the humans that wish to study them are not. To discover more about the unique wildlife that inhabits these limestone caverns, modern researchers need to be cavers, divers and fishers all at once. But why go to all this trouble?

The reason is an urgent one: we need to discover all we can about this remarkable ecosystem before it is lost forever. The Balkans’ last remaining wild waterways are threatened by proposals for dams, hydropower projects and many other modifications. “Building dams is disastrous for the very sensitive organisms that inhabit places with such specific conditions,” says Marijana Demajo, BPSSS (BirdLife Serbia), Balkans Small Grants Co-ordinator for Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Mediterranean*. “Underground life depends on the water level; it’s fed from the surface watercourses.”

For example, when the Trebišnjica River was enclosed in artificial concrete channels in Bosnia & Herzegovina, it cut off the natural flood water that usually reached sink holes at the edges of the Popovo Polje plains. As a result, large colonies of exclusively cave-dwelling tube worms were completely killed off within the sink holes. Fortunately, the more we know about an ecosystem, the more information we have to make positive change to policy. And so CEPF brought together experts from the Subterranean Biology Lab at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and the Center for Karst and Speleology, based in Bosnia & Herzegovina. Together they formed the SubBio Code project. Their mission: to develop new tools to identify and catalogue the rich underground biodiversity of the Dinarides region in Bosnia & Herzegovina.

“This a landscape full of life, not some lifeless place. The discovery of new species is important in order to demonstrate the true value of karst [limestone] landscapes, and to show that they are not just geomorphological formations, but a living system,” asserts Demajo. “And let us not forget the importance of educating the local community.”

This March, researchers braved freezing snow and flooded caverns (and multiple COVID tests) as they ventured back out into the field to survey this little-known network of caves. Over just a few days, they advanced the knowledge of the habitat and its wildlife further than ever before. One day, researchers were sampling springs for shrimp-like amphipod crustaceans when they met local people who, surprisingly, knew about the shrimps’ existence and had given them the name šmugarica. Later the same day, they dispelled a false rumour about the cave Ratkovića Pečina, which was thought to stretch far back into the hills but turned out to be of normal dimensions. Towards the end of their visit, a local caver showed them a cavern full of bats whose guano provides nutrients for a thriving ecosystem of invertebrates. The team used their abseiling and rock-climbing experience to survey the area vertically and visit three caves in the side of Korita hill.

Rock climbing is just one of the practical skills that team members have acquired as part of the project’s mission to train and educate scientists, students, volunteers and the local community in the research and conservation of these caves. As well as netting creatures directly from the water, the team also uses an exciting new technique using eDNA (a shortening of ‘environmental DNA’), developed by a previous CEPF-funded project as a way to detect the presence of Olms without capturing and disturbing them. eDNA is the genetic material that gets released by animals as they go about their lives – in the form of skin, mucous, faeces and many other kinds of fragments. Scientists are able to detect this material in the water and identify which species it belongs to, helping them to map its distribution and make conservation plans.

“It is an amazing experience to see something that only a few people in the world have seen before you – or occasionally, to be the first person ever to see it.”Dušan Jelić, Croatian biologist and cave diver

As fascinating as this is, no part of their research is as nail-biting as underground diving. Croatian biologist and cave-diver Dušan Jelić, who discovered the largest known population of Olms in his native country, explains what it’s like to put on full scuba gear and venture beneath the surface of the water to observe first-hand the creatures that inhabit the gloomy depths. “It is an amazing experience to see something that only a few people in the world have seen before you – or occasionally, to be the first person ever to see it. Sometimes it can be scary, just to be underwater, in a small space, isolated from the rest of the world … but mostly it is a wonderful feeling.”

It is a rare privilege to venture into the realm of the Olm, however fleetingly. And though these creatures are perfectly at home in the dark, by shining a light on them we can secure lasting safety for the unique and beautiful world that lies beneath our feet.

Ground-breaking research into rare cave-dwelling fish

In 2020, another exciting new project by the Croatian Biological Research Society set out to investigate the Southern Dalmatian Minnow Delminichths ghetaldii – a rare freshwater fish found only in southern Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia. Although the species is already known to use caves, this project could confirm its status as Europe’s first exclusively cave-dwelling fish. During September and November, researchers surveyed 19 caves through fishing and cave diving, and consulted experts from Croatia and France to set up eDNA methods. They are also laying the foundations for a conservation plan for the species, and forming a network of experts and decision-makers through which to share knowledge.

“We’re working on a rare fish, so it’s really amazing when you actually find it – especially in large numbers, or in places where you don’t expect it to be present,” says project co-ordinator Matej Vucić. “It’s a really good feeling to know there is still hope to save something you’re working on – but only if everyone acts quickly and seriously.”

“It’s a really good feeling to know there is still hope to save something you’re working on – but only if everyone acts quickly and seriously.”Matej Vucić, project coordinator

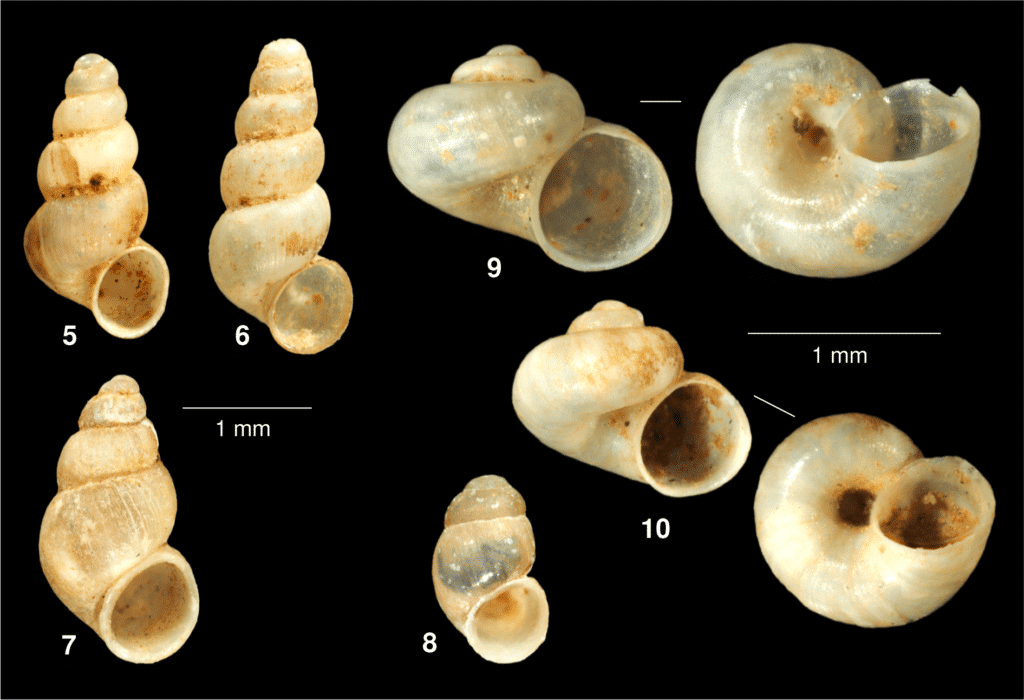

New freshwater snail species discovered

The Center for Karst and Speleology discovered five species of snail never before seen in Bosnia & Herzegovina, as part of a project to survey the country’s freshwater snail populations and the water quality of its limestone rivers and springs. In an exciting turn of events, four of the snails were completely new to science. One of the snail species was discovered during a field trip as part of a student workshop, showing that training new researchers can sometimes pay off instantly!

More worryingly, the team also found species of invasive freshwater molluscs, including the limpet Ferrissia californica, which had come all the way from North America. The next step will be to define the conservation status of the native snails on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Improving knowledge of the Subterranean Biodiversity in Bosnia and Herzegovina is just one part of University of Ljubljana’s project that aims to develop new tools to identify and inventorize the rich subterranean biodiversity of the Dinarides region in Bosnia. As part of our Lessons Learned series to share advice from civil society organisations, here’s some conservation insight from Dr. Maja Zagmajster, SubBIOCODE Project coordinator at University of Ljubljana:

“where there is a will, there is a way. Believe in your idea and do not give up even if you think nothing is working”

Your project is tackling an important conservation problem. What inspired you to find a solution?

The Dinarides in the Western Balkans is a globally significant and exceptional region regarding the richness of species that live exclusively in subterranean habitats. Within this global hotspot of subterranean biodiversity, there are two areas with the highest subterranean species richness. One in the southeast includes the Trebišnjica River catchment in southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. The region consists of a number of karst fields connected by surface and underground water flows. Although it is an area of global importance for subterranean biodiversity, this world’s natural heritage is under threat.

In the mid-1960s, construction of a series of hydroelectric power plants (HE) began on the Trebišnjica River, where a large part of Popovo polje has been severely affected by river channels, dams and tunnels built for HE. Recent socio-economic development in the region has revived plans for several hydropower plants and tunnels also in the Upper horizons of the river catchment. As a result, the natural water regimes and connectivity are altered, and this exceptional subterranean biodiversity is severely impacted.

As part of the project, we considered it extremely important to improve knowledge of the region’s subterranean species and facilitate access to all data for decision-makers to use in conservation and planning efforts. We evaluated conservation statuses as well as important sites for conservation. We have established a web interface for an online database that is a unique example of open access to such data. A critical aspect was also to educate the general public, students, cavers and natural scientists about the value of subterranean biodiversity. Protecting this natural heritage also means protecting groundwater, the vital source of drinking water.

Tell us one big lesson that you’ve learned from this project.

In general, where there is a will, there is a way. Unfortunately, our project was affected by the pandemic shortly after it started. This prevented us from travelling and conducting field research for a year. We decided to approach project implementation differently. Since we could not go into the field, we devoted our energy to analysing samples stored in our collections from previous field research expeditions in the project area.

We also found a way to reach interested individuals by organising online lectures and networking using online tools. While this was not ideal, it was the right way to move project activities forward. When we were finally able to travel and involve interested cavers and students in the fieldwork, it was a big step forward. It is important to involve the people who live in the areas because they are the ones who have a direct interest and benefit from a protected environment.

Given your experience working on this project, what advice would you have for another conservationist in the Mediterranean who is just starting out?

Believe in your idea and do not give up even when you may think it will not work. Do not be afraid to tackle even the most complicated conservation issues; even a tiny difference you can make to improve conservation is worth it. Involve local communities and all interested stakeholders to show them that change and a different perspective are possible.

*The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, and the World Bank. Additional funding has been provided by the MAVA Foundation. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation.

CEPF is more than just a funding provider. A dedicated Regional Implementation Team (RIT) (expert officers on the ground) guide funding to the most important areas and to even the smallest of organisations; building civil society capacities, improving conservation outcomes, strengthening networks and sharing best practices. In the Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot, the RIT is entrusted to BirdLife International and its Partners: LPO (BirdLife France), DOPPS (BirdLife Slovenia) and BPSSS (BirdLife Serbia).Find out more at www.birdlife.org/cepf-med

Related news

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

By Sofia Capellan

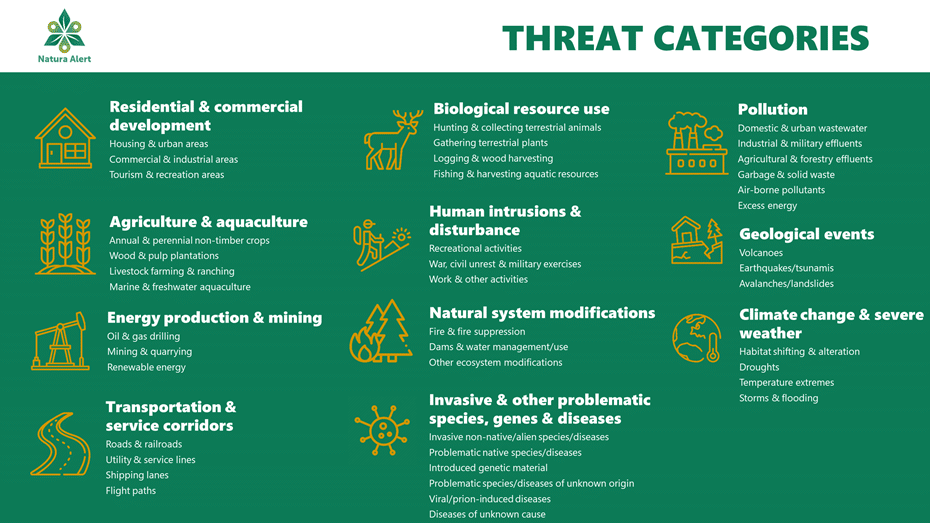

As part of our Horizon 2020-funded LandSense project, BirdLife developed Natura Alert: a mobile and web platform which enables anyone to sound the alarm when they discover nature at risk, in any corner of the world. Natura Alert allows you to report the location of the threat you discover, upload photos and videos of the sites and submit reports.

Once you have submitted this information, it will be verified nationally by IBA and Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) coordinators, as well as by BirdLife International.

Natura Alert is already being used by the volunteer networks of our BirdLife Partners SEO/BirdLife in Spain and Burung in Indonesia. In Spain, volunteers are using it to report threats to birds and habitats within IBAs and Natura 2000 sites, while Indonesian communities are validating alerts from satellite-image analysis of forest change on the Flores island.