Restoring nature puts food on the table

Give someone a fish, they’ll eat for a day. Restore someone’s bay, they’ll eat for the rest of their life.

By Zafer Kizilkaya, President of the Mediterranean Conservation Society

My name is Zafer Kizilkaya. I am a marine conservationist and underwater photographer. I would like to tell you about a project I worked on that is particularly close to my heart: the restoration of Gökova bay.

Thirteen years ago, this large bay, a traditional fishing spot in southwestern Turkey, was in horrific condition. The bay had been so overfished, it had the lowest amount of fish per square meter in the entire Mediterranean basin. When I went diving there, I saw an underwater desert. On top of that, the place was littered with discarded fishing gear, and schools of invasive Rabbitfish (Siganus) were destroying the endemic aquatic vegetation. Nature was so degraded, it was affecting the fishing community’s income, thereby hurting the local economy.

I couldn’t take it. I needed to act. In 2009, I launched a project to establish ‘No Take Zones’ in the area – places where you’re not allowed to fish or engage in any other extractive activity. After long negotiations with the fishing community and other stakeholders, in 2010, the government officially designated No Take Zones in the bay!

Alas, that was just the beginning. Claiming a temporary fishing ban is one thing, enforcing the ban is quite another. I invested a lot of effort into this by establishing a marine ranger system with speed boats and local rangers. In the meantime, there was a massive underwater clean-up to remove hundreds of kilometres of abandoned nets and fishing lines.

Our work soon paid off: today, the amount of fish per square meter is ten times what it was before. The clean-up (which still has to take place every year), also enables sponge species to flourish, creating another micro ecosystem, supporting many species as shelter.

As the local apex predator species, such as Dusky groupers (Epinepheus marginatus) and Common dentex (Dentex dentex), increased in number and occupied the bay, the numbers of invasive species decreased under the preying pressure. This, in turn, helped certain macroalgae species reappear.

One animal that particularly benefitted from Gokova Bay’s restoration is the critically endangered Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus). There were only a couple left as recently as 2013. Now, there are eleven, a great achievement considering there are only around 100 in the whole country!

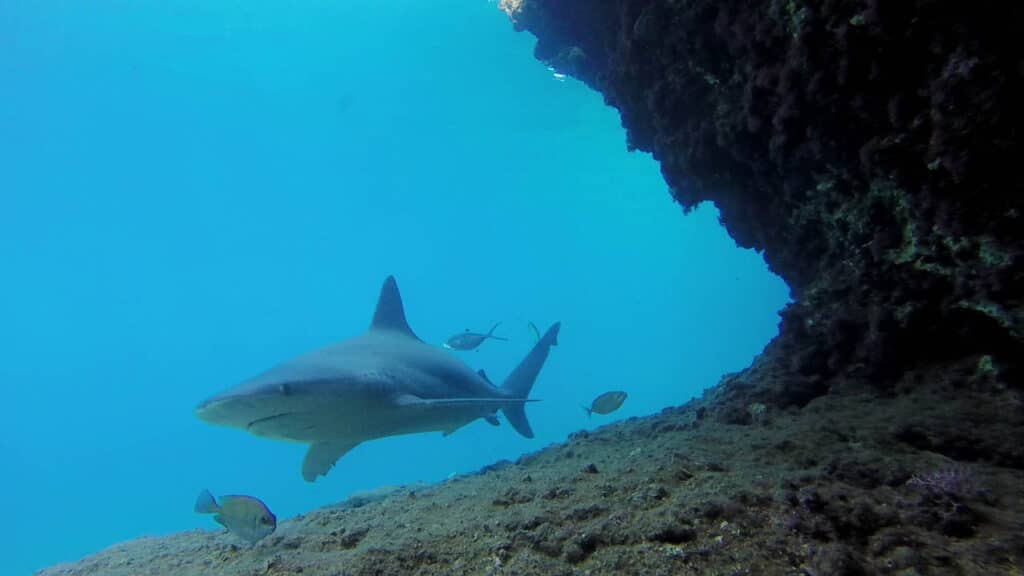

Butterfly ray (Gymnura), amberjack (Seriola) and endangered Sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus) populations have significantly increased, too. Gökova Bay is the only Marine Protected Area in the Mediterranean with sharks.

At the very beginning of this initiative, as you might imagine, the fishing community was strongly opposed to No Take Zones, as they thought they would lose their source of income. But the truth is, overfishing, and the subsequent destruction of marine life, was driving down their income. Today, commercial species at Gökova Bay are plentiful, and fishing there is both sustainable and profitable: the fishing community’s income has increased by 400%! We created employment for fishers, rangers and divers, as well as conservation biologists. The restoration of the bay has been good news for the local economy as a whole.

One great thing about this project is that it could easily be replicated elsewhere. In fact, other Mediterranean countries come for exchange visits and training programs. Even within Turkey, we are now trying to replicate our success in other parts of the country. For many, changing our ways of managing resources are doubted and losses are feared, but we hope to work with everyone to convince people of the great benefits restoration can bring.

If I had one message for policymakers, it would be this: we don’t just need new targets, we need action. Real No Take Zones with proper enforcement. Protection on paper is not enough. In an extremely overfished and warming world, we must invest in restoration. Otherwise, the natural and economic bill will be too high.

I would like to thank everyone involved in the restoration of Gökova Bay. All the staff from the Mediterranean Conservation Society including, but not limited to, the rangers, the monk seal conservation group, the sandbar shark conservation group, the clean-up group, the marine ecosystem restoration groups, and the fisheries management group. Thank you to the coast guard, the Ministry for the Environment, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and the visitors who made anonymous donations after snorkelling in the bay and witnessing the restored marine ecosystems.

According to the latest research, for every dollar spent in marine conservation, you get eight dollars back. Nature is the foundation on which all else stands, so profitability really shouldn’t be the decisive factor when thinking about restoration. Nonetheless, the fact remains that there are economic benefits to protecting the planet – so what are we waiting for?

Beyond Gokova bay

The story of the restoration of Gökova Bay is magnificent, and it’s not unique. Large-scale nature restoration has been proven to also provide economic benefits in other places, too. Here are just a few examples.

The LIFE Herbages project in Belgium, run by BirdLife Partner Natagora, was a seven-year endeavour to improve the biodiversity and connectivity of over 400 hectares of meadows, grasslands, marshes and humid forests. This project provided a great stimulus to the local economy: it mobilised 125 local companies to work on construction, agriculture, forestry and more. The ecosystem services generated by the restoration are estimated to be worth over one million euros per year: €40,000 in pollination, €50,000 in water purification, €100,000 in flood protection, €180,000 in carbon storage, €260,000 in better quality food for livestock, and €400,000 in educational and recreational value.

The Eco Astillero XXI project in Spain, run by SEO/BirdLife Spain and the city of El Astillero, transformed a heavily degraded and inaccessible landscape into a lush green and blue space for all the city to enjoy. Every year, unemployed people are hired to work on the site: removing invasive plants, digging ponds, planting trees, setting up nest boxes, and more. The project has employed 560 people so far! Moreover, thanks in part to the new trails and bike lanes, El Astillero is now an eco-tourist destination.

Oroklini Lake, a Cypriot wetland home to the Spur-winged Lapwing (Vanellus spinosus) and the Black-winged Stilt (Himantopus Himantopus), was severely degraded. Now, thanks to nature restoration, wildlife is coming back! And wildlife isn’t the only beneficiary, thanks to the construction of nature-watching hides, footpaths, information points and more: Oroklini lake is now a key eco-tourist destination of Cyprus’s Larnaca district. The LIFE Oroklini project was launched in 2012 and coordinated by BirdLife Cyprus.

Episode 1 – Bringing nature back to the Berlengas archipelago

Episode 2 – How restoring peatlands can help us beat climate change

Episode 3 – How restoring nature keeps the floods at bay

Episode 4 – Restoring nature puts food on the table

Episode 5 – Restoring nature, restoring joy

This story is part 5 of a series called The rewards of nature restoration, a joint project run by BirdLife Europe & Central Asia, UNEP-WCMC and supported by the Endangered Landscapes Programme – with funding from Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |