Plains and Pampas Wanderers: The Mid-continental Americas Flyway

The awe-inspiring phenomenon of migration is not just coastal – in the Mid- continental Americas Flyway, many species fly in their millions between North and South America, encountering numerous challenges along the way. The most endangered species undertaking this journey are beginning to be protected by a new set of internationally connected conservation projects, aiming to maintain the integrity of the whole flyway.

By David Callahan

Header image: Flocks of thousands of Snow Geese on migration provide one of the great spectacles of the Mid-continental Americas Flyway © Raymond Hennessy

In the Native American myth of the raven and the goose-wife, a raven spends his time sharing his bountiful habitat with thousands of geese, but becomes lonely when they depart south for the winter. He falls in love with a female goose and decides to leave with her the following autumn. However, he is too weak a flyer to keep up with the geese and can’t find enough food for the journey. The goose-wife tries to carry him on her back but he is too heavy and slows them down. When they come to the ocean, he realises he can’t make the crossing and decides to stay. This, so the story says, is why ravens are present all year, while the geese come and go as they please.

There is an element of truth to this folktale. It takes a lot of energy and effort to migrate, and all birds must have enough sustenance to cross large expanses of land and ocean, and have stop-over sites along the way with enough food and undisturbed space to rest and roost. Birds have evolved fine-tuned abilities to connect the dots between such sites over entire landscapes, but they are confined by geography, habit and instinct.

Straight down the middle

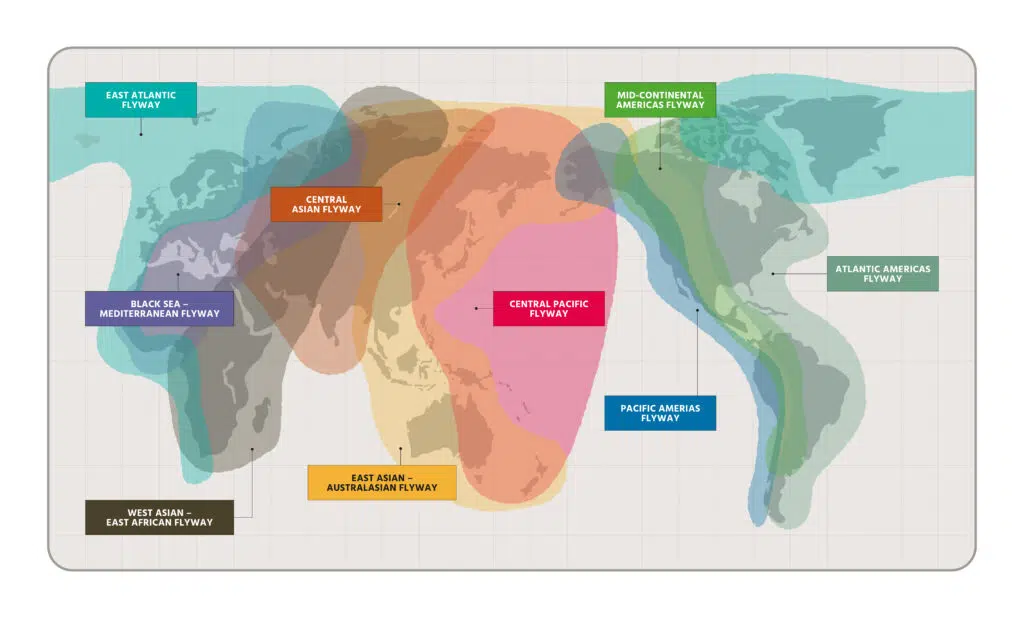

These parameters form and constrain the world’s nine major bird migration flyways, and the Mid-continental Americas (aka Central Americas) Flyway is one of three major routes found in the New World. It extends more than 14,000 km, from northernmost Arctic Canada to the southernmost tip of Tierra del Fuego, and is more than 30.4m km2 in area. This vast expanse of land across two continents contains huge tranches of the major inland North American habitats, from the northern tundra, through boreal forests and arable prairie, and down the immense Mississippi River to marshes and sea on the Gulf Coast of Texas.

There, a fork appears in the road. Some birds cross the Gulf of Mexico to the Yucatán Peninsula, but others take the long way around, funnelled through the tropical forests of Central America. These two expressways eventually lead to the South American forests and grasslands, stretching down through the pampas and cerrado to Patagonia – all rich wintering grounds.

These Neotropical habitats are essential for huge numbers of migrants, though some do not go quite that far, and wintering areas and stop-overs can be anywhere south of the tundra, depending on the species. The whole global corridor is essential for the survival of 382 species, ranging in size from the diminutive Ruby-throated Hummingbird to the huge Whooping Crane.

Wandering waterbirds

The signature migrant of the Mid-continental Americas Flyway – certainly its most dramatic in numbers, noise and spectacle – is the indigenously mythological Snow Goose. About 15 million of them breed on the high North American tundra, migrating directly south to spend winter on the Mississippi floodplain and Gulf of Mexico. Snow Goose is undergoing an expansion in numbers, despite still being hunted, due to its ability to use agricultural habitats for winter feeding and the inaccessibility of its breeding range.

This is not the case with another large and charismatic species dependent on the flyway: Whooping Crane. This large, white, 1.5-metre-high crane is the tallest bird in North America – but it’s in a precarious position. In 1941, only 21 remained, with 15 wintering at Aransas, Texas, and six sedentary birds in Louisiana. The migratory population is now known to breed at Wood Buffalo National Park, Alberta, Canada, and had expanded to 283 by 2011 – still worryingly low, but increasing at 5% annually. The total population – wild and captive – was then 599, and increasing.

Whooping Cranes depend on inland freshwater wetlands, which have historically been under intense agricultural drainage pressure. Always rare, in 1870 the species was already down from a pre-colonisation population of 10,000 to 1,500, and the return climb has been arduous. The fact that it is now fully protected in all its breeding, wintering and stop-over sites is a major achievement for the flyway. The Platte River Recovery Program in Nebraska is protecting the species at a key stop-over site. However, the remaining sedentary birds were hit hard by a hurricane in 1940, highlighting that climate change is now the major threat to the species.

Inland shorebirds

Despite being inland, the Mid-continental Americas Flyway is crucial to migrating shorebirds. Millions venture in a broad swathe across the North American interior, taking advantage of permanent and temporary wetlands to refuel and rest.

Shorebirds have to cope with several innate biological hindrances, not least a small clutch size and, for many species, habitual long-distance migration. Their nesting, resting and foraging habitats – grasslands, beaches and marshes – have been in high demand for humans over the last century, and continue to suffer from huge developmental pressures, creating massive problems for conservation.

The Midcontinent Shorebird Conservation Initiative was set up to allow joined-up collaboration between international governments, NGOs and academia to find new ways of protecting these inland shorebird habitats. It prioritises 26 ‘focal species’ using the flyway. Not all are migratory, but protection of the most threatened helps conserve others.

Many New World shorebirds have declined, though most are considered Least Concern by the IUCN. The most vulnerable are six species classified as Near Threatened. Two of them, Buff-breasted Sandpiper and Red Knot, perform long migrations from the northern to the southern hemispheres, while Mountain, Piping and Snowy Plovers migrate within North America (the last-named species also has a resident population in western South America). The sixth species is the odd one out: the entire 1,500-strong population of Magellanic Plover, a South American endemic and Austral migrant, moves north through Argentina from its southern breeding grounds at the opposite time of year.

The flyway also hosts incredible movements of more common shorebirds, including 1,295,000 Pectoral Sandpipers, 780,000 Wilson’s Phalaropes, 730,000 Upland Sandpipers and 400,000 American Golden Plovers. Numbers of transient Long-billed Curlews, Marbled Godwits and Western Sandpipers occur in low six figures. Of more conservation concern are the 11,100 Snowy, 3,500 Piping and 17,500 Mountain Plovers – all mostly short-distance North American prairie migrants and all a significant percentage of their global populations.

Buffer zone

Buff-breasted Sandpiper is the conservation priority shorebird along the flyway, owing to its steep decline since the 19th century. Almost the entire global population of 56,000 uses the flyway to switch between tundra meadow breeding habitat (notably, Banks Island, Canada, and the Prudhoe Bay/Kuparuk oil fields, Alaska), largely unprotected upland grassland staging posts on the Great Plains (including Beaverhill Lake, Alberta, and sod farms in Texas, Oklahoma and Minnesota) and the pampas grasslands of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, where it winters.

Buff-breasted Sandpiper’s decline from its former millions started with hunting – the species was famously approachable. While the Migratory Bird Treaty (1918) stopped commercial killing, post- colonial habitat loss and degradation soon compounded its decline, whether by agriculture, overgrazing, pesticides, draining, fire or flooding. Drilling for oil and gas in the Arctic is now beginning to inhibit breeding success and it is likely that climate change will transform much of its range for the worst. A conservation plan has now been developed across the flyway to address the lack of detailed knowledge about its requirements.

Passerines descending

The famously huge raptor populations that use the flyway are relatively healthy. These include Swainson’s Hawk, which breeds as far north as eastern Alaska and migrates up to 13,000 km or more to winter mainly in the pampas of central Argentina. Songbirds are another story, however, and several species are of conservation concern.

The Near Threatened Eastern Meadowlark is declining throughout its range in Canada and the US, due to disturbance and changes in agricultural practices. The reconstitution of grasslands through the US Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program promises to help turn this around. The Vulnerable Chestnut-collared Longspur is a true plains species, migrating from northern prairies to southern grasslands and the Chihuahuan Desert. Its breeding range has contracted owing to the exploitation of native prairie for agriculture. Management to expand these habitats is not undertaken specifically for this species, but where it exists, the longspur and other prairie specialists benefit.

Of particular North American conservation interest is Cerulean Warbler, one of many wood- warblers that migrate to Central and South America. Breeding in mature, broad-leaved forests, it is considered Vulnerable owing to forest clearance and subsequent fragmentation throughout its range. There is a habitat conservation plan in Tennessee, while land reclamation is being explored in its core range in the Appalachian mountains.

It winters in mature subtropical montane forest, and BirdLife partners Calidris in Colombia and Aves y Conservación in Ecuador both work on Andean habitat restoration, benefitting wintering Cerulean and Canada Warblers. Calidris in particular works with local communities, building grass-roots conservation networks and encouraging leadership in local women. There is also evidence that shade-grown coffee plantations are favoured by Cerulean Warbler in winter, enabling it to exist in some degraded habitats.

Commoner North American songbirds are parasitised by another declining species: Yellow- billed Cuckoo. Considered Least Concern, it is declining fast enough to be a Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act priority species. This grant programme is supported by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and funds projects from Canada to southern Latin America.

Although the cuckoo is still fairly common, it declined between 59-67% in the 43 years prior to 2014. It is particularly sensitive to pesticides and building collisions, while the fragmentation and degradation of its favoured breeding and wintering riverine woodland habitat also chip away at its numbers. It winters in the Gran Chaco forest region of the Rio de la Plata, and there are two major projects to conserve and restore that habitat in Argentina and Paraguay, with BirdLife partners Aves Argentinas and Guyra Paraguay working together to establish new protected areas, with the close involvement of local communities and indigenous peoples. There are also habitat restoration efforts taking place in California, where it is now rare, but once bred.

The lesser-known south

The Endangered Golden-cheeked Warbler has a shorter migration from central Texas, where it has a limited breeding range in juniper-oak woodland, to Nicaragua, where it winters in pine and oak woodland and cloud forest between 900-2,200m.

There has been a drop in its numbers, with current breeding pairs estimated at no more than 16,000, and probably less. Its favoured woodlands are fragmented and degraded, but efforts to preserve large tranches of habitat have been underway in Texas since the early 1990s, in the Balcones Canyonlands NWR and Fort Hood Military Installation (which hold 800 and 4,500 pairs respectively). Several of its known wintering sites in Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras are now protected from the surrounding rapid deforestation.

Even less is known about Central American and Austral migrants, but many use the southern hemisphere part of the flyway. The largest group there are the 76 species of tyrant flycatcher, which make up half of the passerines, and a third of all Austral migrants that use the flyway. Many move north into Amazonia for the winter, but are either of Least Concern or unknown conservation status. Even so, most are likely to benefit from more holistic, modern conservation projects.

International rescue

The US and Canada are currently not signatories of the Convention on Migratory Species, which prioritises investment between nations to build stronger conservation links – however, most South American countries are. BirdLife has instituted two Conservation Investment Strategies for Birds in the Ecuadorian Chocó-Andes (cloudforests that host numerous Austral and Nearctic passerine migrants) and the Southern Cone Grasslands (a temperate and subtropical biome in Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil) that holds huge biodiversity, including most of the migrant shorebirds that breed in North America.

While not currently threatened, Wilson’s Phalarope is one of many beneficiaries of the newly created Parque Nacional Ansenuza in Argentina, developed by Aves Argentinas. This holds the largest wetland in South America, hosting 600,000 phalaropes, as well as 66% of all migratory shorebirds that visit each winter. Conserva Aves is an initiative jointly protecting the Pacific and Mid-continental Americas Flyways from northern Mexico to southern Chile. This robust international collaboration will be protecting the most biodiverse region on Earth, with the tropical Andes hosting numerous endemic tropical forest species, as well as millions of North American breeding songbirds.

This two-continent route is fraught with dangers – and most are now anthropogenic. With continued advances in knowledge, we can try to make a difference. There are other versions of the goose-wife myth, where a man marries the goose and their children grow up to be birds – perhaps an apt metaphor for the hoped-for results of human intervention. BirdLife partners’ internationally linked conservation endeavours should help to maintain and expand the rich habitats along the flyway, and hopefully help those threatened birds within it to recover.

BirdLife is committed to safeguarding the world’s flyways and the millions of birds that migrate along them. Find out how you can help here.