Exodus: The Pacific Americas Flyway

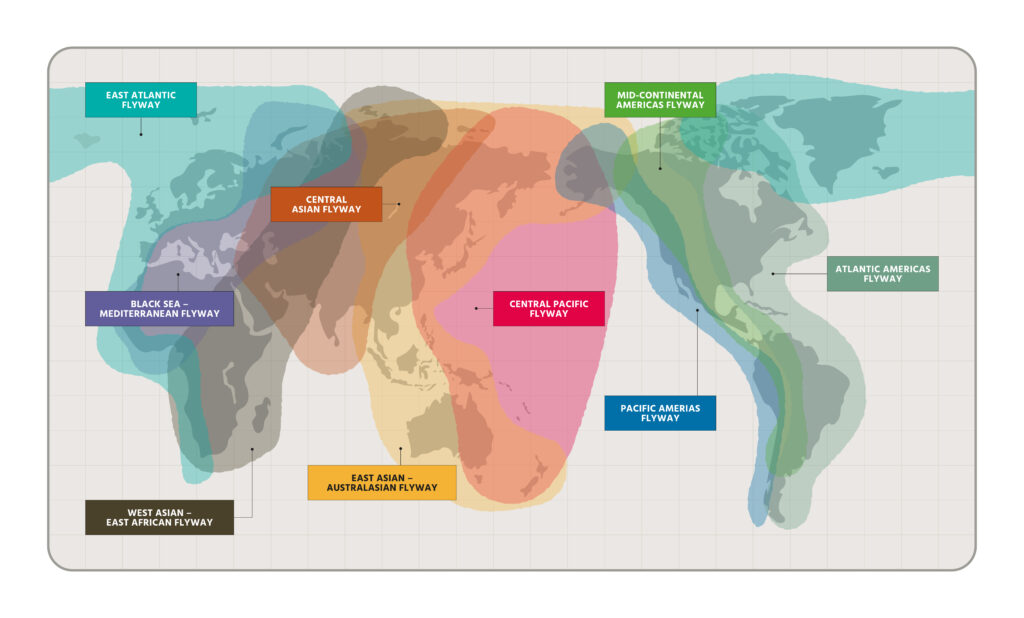

Migration is one of the most compelling aspects of the avian world, with billions of birds travelling vast distances across the globe twice each year. Many do so along well-established routes known as flyways, and there are nine such major flight paths around the world. We take a look at the Pacific Flyway in the Americas, its special species, sites and habitats, the threats facing birds migrating along the route and the vital work underway to protect them.

Western Sandpipers migrate along the Pacific Flyway in spectacularly large flocks © Certhian Photography/Shutterstock

By Eliana Montenegro and Barend van Gemerden

The spectacular journeys of migratory birds have held a special fascination throughout human history. With the advance of science and technology we now understand much about bird migration, but many mysteries still remain. The predictable unpredictability of this wonder of nature is one of the undeniable attractions of birdwatching.

Many species migrate along broadly similar, long-established ‘corridors’ from their breeding grounds to non-breeding areas, often over distances of thousands of miles. The Pacific Flyway is one of three such routes in the Americas, stretching from the permafrost tundra of the high arctic, south along the Pacific seaboard to the Neotropics, and ultimately on to Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the South American continent.

Many of the millions of migratory waterbirds that nest on Alaska’s expansive tundra embark on remarkable southward journeys along this flyway. They are joined by travellers from other remote breeding grounds, including Long-billed Dowitchers from across the Bering Sea in Arctic Russia.

Most birds follow the Alaskan coast south via traditional staging sites such as the Copper River Delta in south-central Alaska. Others, notably sea ducks and Cackling Geese, cross the Gulf of Alaska directly from their breeding grounds on the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands, joining the Pacific coast near the Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia, Canada. From there, they continue to their wintering grounds further south.

Globetrotting Shorebirds

Whimbrels are the true champions of the Pacific Flyway. A bird that was satellite-tagged on its breeding grounds on the Collville River in far northern Alaska embarked on a seven-stop journey to the mouth of the Río Maipo in Chile. After five months the bird, named T6 by researchers, started its northward journey. With only two stops on the way, T6 was clearly in a hurry to get back to its Alaskan breeding grounds. In one year, T6 flew almost 18,500 miles from Alaska to Chile and back again.

Apart from being able to travel such huge distances, Whimbrels are also remarkable at switching their diets. On their breeding grounds, birds feed principally on berries, lichens and mosses, but once they start travelling and move to muddy coastal wetlands, they become expert hunters of crabs and other crustaceans, especially in coastal habitats in Panama.

Surfbird is another great traveller, one of several waders that inhabit rocky shorelines along the Pacific coast of the Americas. The species’ remote mountain breeding grounds were only discovered in 1926, and its breeding ecology remains poorly understood. More than 75% of the population breeds in Alaska, with smaller numbers in the western Yukon Territory, Canada. The species has perhaps the longest wintering range of any bird in the world, extending along the Pacific coast of the Americas from south-eastern Alaska to southern Chile.

The most significant sites for migrating Surfbirds are Alaska’s Homer Spit and Northern Montague Island. These Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) have hosted as many as 40,000 and 10,000 birds respectively during spring migration. The global population was estimated at 70,000 individuals in 2000, and Christmas Bird Count data from the North American Pacific coast reveal that it declined by an average of 1.2% per year from 1959 to 1988.

The species is inherently vulnerable because the majority of the population becomes concentrated in the region of Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska during migration. There is therefore considerable risk from a catastrophic oil spill – the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil disaster in Prince William Sound occurred within just a few kilometres of the Northern Montague Island IBA but, fortunately, on that occasion the species was largely unaffected.

OTHER MOVEMENTS

Elegant Tern is another long-distance migrant of the Pacific Flyway. This species has a restricted breeding range, with the bulk of the population nesting at Isla Rasa IBA in Mexico’s Gulf of California. The population there was estimated at 45,000 individuals in the early 1990s, representing no less than 90-95 per cent of the global breeding population. A smaller colony of about 550 birds exists to the north on Isla Montague, within the Delta del Río Colorado IBA.

The species is a relatively recent addition to the breeding avifauna of southern California, with a colony first discovered at San Diego Bay in 1959. In 1996, this colony was estimated to number 3,740 birds, but the population has since declined considerably. A second Californian colony, originally at Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve, has since shifted north to the Terminal Island Tern Colony IBA in Los Angeles harbour.

Elegant Terns start their post-breeding dispersal in late May. Birds initially move northwards along the coast to central and northern California, and the species can occur as far north as southern British Columbia. Numbers peak between July and September, after which birds head towards South America for the winter. Most have departed the US by October. Their wintering range extends from Nayarit in western Mexico south to Chile and the highest wintering densities occur south of Ecuador, with especially large numbers present at the Reserva Nacional de Paracas IBA in Peru.

Most birds using the Pacific Flyway have their breeding grounds in the north and migrate south for the non-breeding season. However, there are also so-called ‘austral migrants’ – birds that breed in the south and move north after breeding. For example, Rufous-chested Plover is found on inland short grasslands in Chile and Argentina from the coast up to altitudes of 2,000 m above sea level. It favours windy inland foothills, but is also found in boggy lowlands or dry stony areas around upland lakes. After the breeding season, birds move north as far as Peru, visiting flooded grasslands, eroded inland grasslands, marshes, streams, mudflats, beaches and rocky shores.

Against the odds

As well as waterbirds, huge numbers of migratory landbirds travel along the Pacific Flyway. Few are as remarkable as Rufous Hummingbird, often described as North America’s ‘extremist’ hummingbird. It breeds as far north as 61° N in Alaska and migrates to winter in central Mexico. This annual 12,000-mile round trip is the longest of any bird when compared to body length.

Timing is everything for Rufous Hummingbirds, especially those travelling to Alaska. As breeding and raising young takes 38 days, there is only a small window when the conditions are right for the flowers and small flying insects on which they rely. During migration, the birds cleverly choose their route to correspond with areas with the highest abundance of flowers; in spring they fly north, following the lowlands along the coast, and in summer and autumn they go south through alpine meadows in the highlands.

For a number of other landbird migrants, including Vaux’s Swift, Hammond’s Flycatcher and Townsend’s Warbler, Mexico and Central America also represent the terminus of their journeys.

Others, however, continue on into South America. One of the most notable is Olive-sided Flycatcher, which has the longest migration of any North American tyrannid flycatcher: it migrates all the way from the boreal forests of Alaska to winter in the Chocó eco-region that stretches from Ecuador and Colombia as far south as Bolivia.

Although very little is known about landbird migration systems within South America, it appears that several species of ground-tyrant migrate north from breeding grounds in Patagonia. These include Cinnamon-bellied Ground-tyrant, which migrates from breeding grounds in Tierra del Fuego to spend the austral winter (from April to October) in Peru.

Countering Threats

Unfortunately, many of the world’s migratory birds are in decline, and their lifestyles and ecology render them particularly vulnerable to a range of threats. Species using the Pacific Flyway are no exception, and some, such as Peruvian Pelican, Elegant Tern and Olive-sided Flycatcher, are now classified as Near Threatened.

Undertaking such dramatic long-distance movements requires energy and determination, pushing birds to the limits of their endurance. They are reliant on favourable weather conditions and must find sufficient food sources and safe places to roost at multiple sites during their journeys. Yet vital habitats en route to wintering grounds are under significant threat from infrastructure and housing developments, energy projects such as mining and drilling for fossil fuels, tropical deforestation and the spread and intensification of agriculture.

Birds are also at risk through collisions with man-made structures such as powerlines, wind turbines, brightly lit buildings at night an telecommunications masts. Conservative estimates suggest that at least four million birds are killed in the USA each year by collisions with mobile phone towers alone.

Population growth and economic development is increasing the human footprint in many parts of the Pacific Flyway. Coastal wetlands are particularly targeted for fish and shrimp farming, and land reclamation is expanding urban areas. It is heartening that the plans to build new housing estates in large parts of Panama Bay IBA were stopped in 2013 following a national and international outcry led by Audubon Panama (BirdLife partner). Disturbance from recreational activities and feral cats, dogs and other introduced predators further limits the possibilities for migratory birds to breed, feed and rest. Introduced mammals, for example, are a main obstacle preventing Elegant Terns from establishing new colonies.

Climate change is also affecting the migration of birds in different ways. Changes in vegetation and timing of seasonal peaks of insects are currently most pronounced in the arctic. Rapid changes in weather patterns, including the frequency and severity of storms, will increasingly jeopardise the slowly evolved travel routines of migratory birds. Low-lying coastal wetlands, especially those enclosed by hard dykes, are at risk of disappearing completely as a result of sea level rise.

Taking Action for Birds

In the face of such a diverse array of threats, the conservation of migratory birds depends on international collaboration and a co-ordinated response along entire flyways. This includes the management of a network of critical sites and landscapes for migrants, as well as reducing human-induced mortality. BirdLife International’s Flyways Programme unites BirdLife partners along the Pacific Flyway to address the main threats to migratory birds.

Birds Canada and Nature Canada (BirdLife partners) are campaigning against port development plans that will put Fraser River Estuary IBA, home to an incredible 95% of all Western Sandpipers on migration, at risk. Audubon Panama is working to improve climate change resilience and adaptation of the coastal wetland IBAs of Bahia Parita and Panama Bay. Meanwhile, Aves y Conservación (BirdLife in Ecuador) is working with local producers and communities in Jambelí, Ecuasal and La Segua to integrate bird conservation into the management of salt and shrimp ponds, and the collection of crabs.

Shorebirds in coastal wetlands are monitored throughout the Pacific Flyway, with Calidris (BirdLife in Colombia) leading on regular counts in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Colombia and Ecuador. Calidris is also restoring and protecting wintering habitat for Canada Warbler at the Paraguas Munchique Conservation Corridor in Colombia. In addition, BirdLife is leading the development of a conservation strategy for the Ecuadorian Chocó. This forest region is extremely important for resident and migratory species, including the Near Threatened Cerulean Warbler.

Audubon, BirdLife International, American Bird Conservancy and the Network of Latin American and Caribbean Environmental Funds (RedLAC) recently launched the Conserva Aves initiative, which aims to catalyse the establishment of over 80 new protected areas covering 2 million hectares, and improving the management of an additional 2 million hectares.

Stretching from Mexico to Chile, this program aims to establish new protected sites for every bird species classified as Endangered and Critically Endangered. While site work is mostly triggered by endemic birds, the Conserva Aves initiative will also mean a step change for the conservation of migratory landbirds in the Pacific Flyways.

Sites along the Pacific Americas Flyway

Birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway rely on a huge number of sites for feeding and roosting during their journeys. Many of these are classed as IBAs, and they include a diverse range of habitats from marshes and estuaries to tropical forests. The following IBAs are examples of the key sites on which migrants depend:

Copper River Delta, USA: more than 4 million Western Sandpipers and 950,000 Dunlin have been counted at this 399,000-ha stop-over site, which has also supported 11,000 Glaucous-winged Gulls and over 1,150 Trumpeter Swans.

Fraser River Estuary, Canada: classified as an IBA in Danger, its 76,000ha are home to an estimated 1.7 million birds. Over 500,000 Western Sandpipers have been estimated to use the area on a single day during spring migration.

Delta del Río Colorado, Mexico: staging and wintering area of 107,702ha for migratory waterbirds, including more than 55,000 Western Sandpipers, 10,900 Marbled Godwits, 3,000 Elegant Terns and 680 Yellow-footed Gulls.

Upper Panama Bay, Panama: an estimated 1.3 million shorebirds pass through on autumn migration, including 280,000 Western Sandpipers, 47,000 Semipalmated Sandpipers and 30,000 Semipalmated Plovers.

Munchique Natural National Park, Colombia: 80,465 ha of forest in the Chocó eco-region, with over 520 bird species recorded. This is a staging and wintering site for a range of forest-dependent migratory passerines, including Canada Warbler, and is also important for globally threatened non-migratory species such as Colorful Puffleg, Banded Ground-cuckoo and Black-and-chestnut Eagle.

Lagunas de Ecuasal-Salinas, Ecuador: a bird-friendly managed salt pond complex of 500 ha, regularly home to over 44,000 Wilson’s Phalaropes, 2,000 Semipalmated Plovers, 600 Elegant Terns and almost 1,000 Chilean Flamingos.

Manglares Churute and Jambeli Strait, Ecuador: 74,242 ha of mudflats and mangroves home to 10% of the flyway population of Semipalmated Sandpiper and Wilson’s Plover, along with hosting resident Endangered Grey-backed Hawks and Vulnerable Grey-cheeked Parakeets.

Paracas National Reserve, Peru: a coastline reserve of 335,000 ha that hosts 216 species, Paracas is globally important for Chilean Flamingo, Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Peruvian Tern and Elegant Tern.

Río Mataquito, Chile: another IBA in Danger, its 1,200 ha of coastal wetlands host important numbers of Chilean Flamingo and Grey Gull but are threatened by recreational activities and pollution.

This article is the first installment of a new series in the BirdLife magazine profiling each of the world’s nine major flyways. Find out how you can subscribe here.