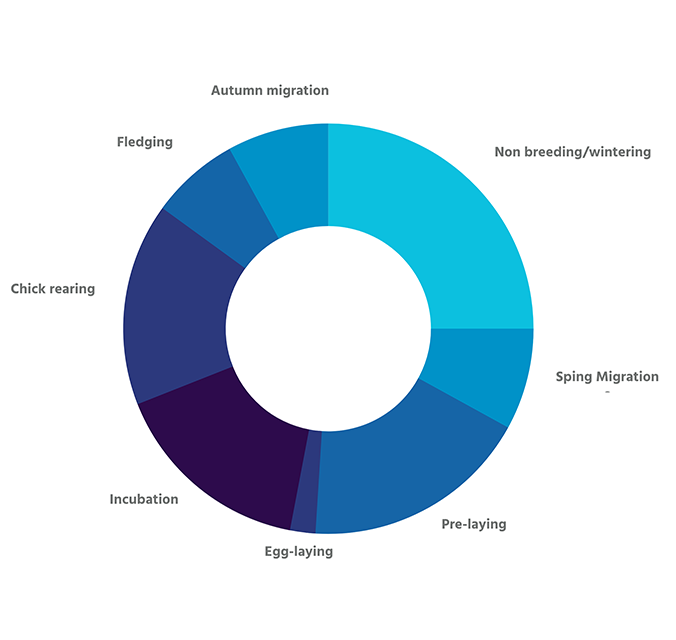

Annual Lifecycle of a Seabird – A winter break: life on the open sea

This is the first in a series of articles exploring the different stages of a seabird’s annual lifecycle.

Written by Daniel Mitchell & Antonio Vulcano

When winter arrives, where do seabirds go, and what do they do?

Although once a mystery, thanks to miniaturized tracking technologies, we have never known as much about the whereabouts and behaviours of wintering seabirds as we do today.

Outside of their breeding season, seabirds no longer need to shuttle between their colonies on land and their feeding areas at sea. This allows them to disperse further offshore to live a more solitary existence, a stark contrast to their crowded, bustling lives in their colonies.

That’s not all. During the non-breeding season, seabirds moult. This energetically demanding process of shedding and renewing their feathers typically occurs at sea. For example, the Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica), with its vivid beak and sharply defined black and white tuxedo feathers during breeding season, morphs to a drab grey, the colours on its beak fade, and its crisp white feathers darken. The makeover is so dramatic that up until the late 1800s wintering puffins were believed to be a different species.

Seabirds in the northern hemisphere winter south of their breeding colonies where the weather is more hospitable and there is a greater availability of food. During the entire non-breeding period, the individuals of some species pass many months without returning to land, braving the often demanding conditions of life on the open sea. The winter period is spent foraging for food and building reserves for the demands of the next breeding season. In some species, such as the Atlantic Puffin, individual birds can use very different wintering locations from one another1, despite even being from the same breeding colony. In contrast, Black-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) from different colonies use the same wintering areas, with individuals from colonies located closer to each other showing a greater overlap.

In some species such as the Common Guillemot (Uria aalge), birds have been recorded returning to some colony sites during the non-breeding season, with these visits regularly increasing as the next breeding season approaches. These colony visits help individuals to secure and defend the highest quality nesting spots within the colony, increasing their chances of successfully raising a chick during the next breeding season.

Seabirds can occur in impressive congregations during the winter. 2.9 to 5 million birds from 21 species winter at the North Atlantic Current and Evlanov Sea-basin (NACES) Marine Protected Area (MPA) – making it one of the most important sites for seabirds across the Atlantic.

Threats

The main threats to seabirds are all well known. Interactions with fishing vessels causes seabirds to get caught in fishing gear (bycatch) and die. Across Europe, it is estimated that over 200 000 seabirds die as bycatch annually.

The designation and proper protection of marine protected areas can help reduce these threats in the most important sites for wintering seabirds, while the improvement of fisheries management and the use of mitigation measures by fishing vessels can reduce the impact across their winter range if applied and enforced at a larger scale.

Overfishing is reducing for seabirds and is likely to be exacerbated in many places due to climate change and rising sea temperatures. Increasingly frequent and severe weather conditions, such as midlatitude cyclones in the North Atlantic, can cause increased mortality due to starvation as rough seas prevent seabirds from accessing their prey or result in changes in prey distribution. Extreme winter events, such as severe storms, can cause seabird wrecks, with large numbers of dead or nearly dead birds being washed ashore. The impact of adverse conditions during the winter has consequences for the following breeding season, with seabirds in poorer conditions having decreased breeding success. Other human activities at sea, such as shipping and offshore wind farms, can also impact wintering seabirds, highlighting the need for sea bassin-level management of all marine activities.

This is why the BirdLife Partnership relentlessly works to tackle these threats and make the ocean a safe and healthy place that allows seabirds to keep doing what they need to do in order to thrive: migrate over the vastity of world’s waters and keep us amazed while doing so.

Image credits: Common Murre (Uria aalge) by Nick Pecker

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |