100 Years and Counting

A century ago, visionary conservationists concerned about the plight of the world’s birds and the wider environment came together to form an international movement. Rooted in the foundations of a handful of campaigning national organisations, it steadily gathered momentum, spread its wings and eventually evolved into a powerful global voice for nature. This is how the BirdLife story began.

By Christopher Sands

Header image: T. Gilbert Pearson, ICBP President 1922-1938

Imagine a sky made dark by an avian eclipse. The Passenger Pigeon, once the most abundant bird in North America, could literally block out daylight when its unimaginably huge flocks passed overhead. Thought to have numbered around three billion individuals, and possibly as many as five billion, this was a gregarious species like no other – a single flock seen in 1866 was estimated to have been 300 miles long. The arrival of European settlers, however, soon changed all that. In just a few decades, under pressure from indiscriminate hunting on a vast scale and extensive deforestation, this most populous of species was rendered extinct, despite having lived in harmony with indigenous peoples for tens of thousands of years. The Passenger Pigeon had been eliminated from the planet in perhaps as little as half a century, with the last confirmed wild bird thought to have been shot in 1901.

‘Natural’ extinction occurs over many hundreds or thousands of years, but human activity has accelerated this rate dangerously.

Other threats to birds in the late 19th century took more novel forms. In both Europe and the United States, the increasing wealth of large numbers of people led to ever more showy wardrobes. For women, the obligatory hat had to be adorned with feathers, both exotic and not, if one was to make one’s mark on the boulevard.

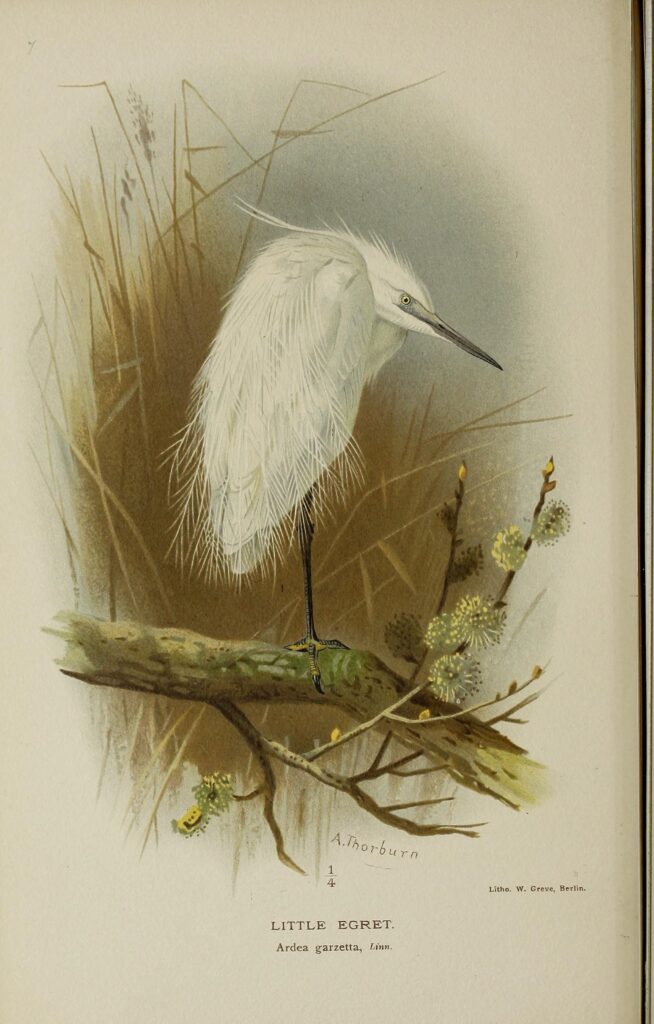

Both our original American Partner, the National Audubon Society, and our UK Partner, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, had their roots in tackling what was called “murderous millinery”. In the words of the RSPB, “In 1889, Emily Williamson created the society with one core aim – to fight a fashion for feathers and exotic plumes that was driving birds including Little Egrets, Great Crested Grebes and birds-of-paradise towards extinction”.

Her all-women movement was born out of frustration that the male-only British Ornithologists’ Union was not acting on the issue. Likewise, in Massachusetts, USA, in 1896, Harriet Hemenway and Minna B Hall organised a series of afternoon teas to convince Boston society ladies to eschew hats with bird feathers. These meetings culminated in the founding of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Our Dutch Partner, Vogelbescherming Nederland (VBN), also had its early roots in successfully campaigning against feathers in hats.

Others joined the battle. According to Cassidy Zachary, a fashion historian, “During a six-month period in 1911, four feather-trading firms sold approximately 223,490 bird corpses in London alone”.

“The blood of uncounted millions of slaughtered birds is upon the heads of the women,” prominent wildlife activist William H Hornaday told the New York Times in 1913. “They have shown themselves a scourge to bird life all over the world.”

NEW AGE, NEW PROBLEMS

After the devastation of the Great War, the world’s industrial economies began to explode – as did their detrimental impact on nature and the environmental quality of life. In parallel, human awareness of these costs was also increasing, with the new phenomenon of radio and motion pictures connecting people in ways seemingly as accelerated as the digital advances of the present generation.

But even in the decades before 1922, the conservation consciousness enmeshed within BirdLife’s DNA was growing by leaps and bounds.

Our oldest Partner, the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), had been working for nature conservation since 1883. Then, as now, birds were an early warning system about the devastating consequences of human activity. Knowledge about how we were destroying nature began to grow in the late 19th century, whether in India, Europe or the Americas.

In addition to BNHS, RSPB and Audubon, many other Partners have been fighting on the front lines for birds and nature for more than a century. Two more founder members, German BirdLife Partner NABU and VBN in the Netherlands, both began life under other names in 1899. The Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union was hatched in 1901, and from it eventually came Birds Australia, which also became a BirdLife Partner.

Dansk Ornitologisk Forening (BirdLife in Denmark) was founded in 1906. The East Africa Natural History Society, which later evolved into BirdLife Partners Nature Kenya and Nature Uganda, first met in 1909, and our founding French Partner, Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO), was established in 1912.

Aves Argentinas started life in 1916 as the Sociedad Ornitológica del Plata. Lëtzebuerger Natura Vulleschutzliga (BirdLife in Luxembourg) was formed in 1920, the Estonian Ornithological Society in 1921, and SVS/BirdLife Switzerland shares BirdLife’s birth year of 1922.

GREAT MINDS

This growing consciousness about how the practices and behaviour of the day were destroying birds and nature brought an eclectic range of concerned people together.

In the UK, an illustrious group gathered in the home of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Robert Horne, the MP for Glasgow. The group included Viscount Grey of Falloden (Sir Edward Grey), who had been Foreign Secretary from 1905-1916, and who later famously wrote The Charm of Birds. He was joined by The Earl Buxton, who had been Postmaster-General and also Governor-General of South Africa.

Frank E Lemon, the Honorary Secretary of the RSPB, Dr Percy Lowe, Curator of Birds at the Natural History Museum, William L Sclater, Editor of the British Ornithologists’ Union’s journal Ibis from 1913-30 and BOU President from 1928-33, and well-known nature writer H J Massingham rounded out the UK group.

Across the North Sea, Dutch conservationists P G Van Tienhoven and Dr A Burdet had managed to protect all wild bird species in the Netherlands in 1912, making it the first country in Europe to do so. Other prominent conservationists of the time included noted ornithologist Jean Delacour of France, who was President of the LPO, and Dr T Gilbert Pearson, founder of the National Association of Audubon Societies, which later became the National Audubon Society.

Out of this noble assemblage, the International Committee (later Council) for Bird Preservation (ICBP) was founded in 1922. In record time, it established Partner organisations in France, the USA, the Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, Hungary, Australia, the UK, Germany, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Norway, Czechoslovakia, Luxembourg, Austria, South Africa and New Zealand.

WOMEN AT THE HELM

At its sixth meeting in 1935, Phyllis Barclay-Smith of the RSPB was appointed as the London-based sub-Secretary to the Secretariat (it was perhaps no coincidence that her aunt, Margaretta Lemon, had been one of the RSPB’s early founders). In 1946 she replaced Count Leon Lippens as Secretary of ICBP. She led the organisation through the 1960s, a pivotal decade in which it started making substantial progress with practical conservation measures, becoming its Secretary-General from 1974-78, assisted in later years by Robin Chancellor.

In 1958 Phyllis Barclay-Smith became the first woman to receive an MBE for work in conservation, and in 1970 she was made CBE. Hers was an impressive period of service, both for its duration and the fact that, unlike the great majority of organisational leaders at the time, she was a woman – echoing the role of Emily Williamson in the genesis of the RSPB, and part of a long-running theme continued by current BirdLife Chief Executive Patricia Zurita.

At the time Phyllis Barclay-Smith retired in 1978, all ICBP posts had been voluntary and unpaid, but the organisation’s membership took the decision to employ a full-time director. On his appointment in 1980, the Swiss conservation biologist Dr Christoph Imboden began to appoint a professional staff to form a Secretariat, whose role would be to develop strategies, programmes and policies.

One of the first five employees was Dr Nigel Collar, who joined as Red Book compiler and is still with BirdLife today. In the same year, the Secretariat moved to Cambridge to share the newly established headquarters of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Species Conservation Monitoring Unit.

In 1985, Cristoph Imboden opened discussion about a new direction for ICBP, as “a network of strong allied national organisations”, and relaunched it as BirdLife International. Its new name and logo was established in March 1993.

The plan worked, and today the BirdLife family is at its strongest, with 117 Partners around the globe working to protect birds and habitats in every continent. The underlying principles which guide BirdLife today were the same as those which led to our creation back in 1922.

Click here to learn more about BirdLife’s history and our 100th anniversary celebrations.

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.