Why it’s important to love birds for more than just their beauty

We all know what our favourite bird looks like – but do you know why it’s evolved to look that way? Discover the amazing new project striving to build a stronger connection between people and nature – through the fascination of bird anatomy.

By Jessica Law

Have you ever looked at a spoonbill and pondered the reason behind its beak’s unique shape, when other waders seem to be doing just fine without one? Birds’ physical features are constantly photographed, recorded and commented on across the ornithology world – but it’s usually just to identify the bird or distinguish it from another, similar species. Information on why birds actually evolved these physical traits in the first place is limited to tiny snippets scattered across the world’s scientific literature.

That’s a real shame – not just because birds’ physical adaptations are fascinating, but also because the more we understand nature, the more we respect and connect with it. As eminent explorer and conservationist Jacques Cousteau once said: “People protect what they love, love what they understand and understand what they are taught.” In today’s era of catastrophic nature loss, such education is fundamental in changing public attitudes.

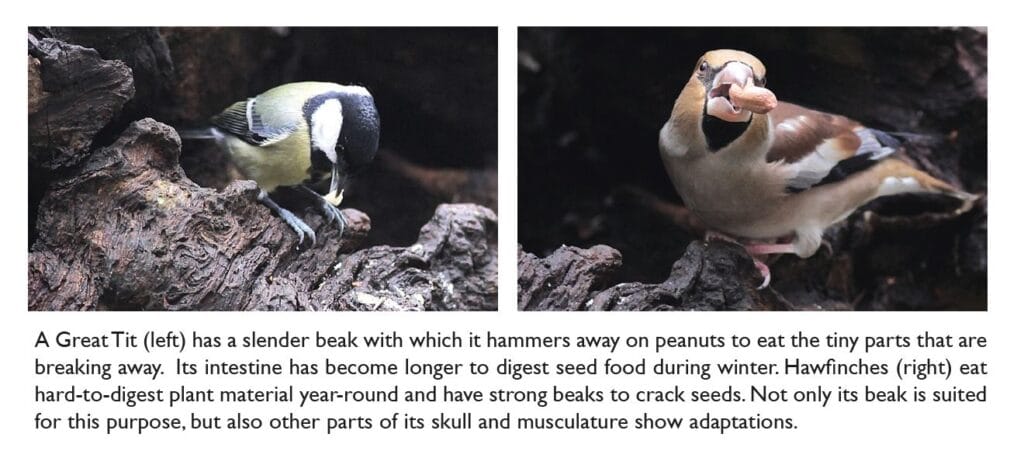

Consider the humble Great Tit Parus major. It’s round and fluffy with cute beady eyes – but did you know that every winter it also adjusts the length of its intestine to accommodate the peanuts we humans feed it, before shrinking it back to digest insects in summer? Next time you see this common bird, you may have more respect for how it copes with the survival challenges it faces.

Knowledge like this also helps the public to understand why it’s so serious when a bird species declines or goes extinct. It’s not just a pretty bird disappearing thousands of miles away – it’s the loss of a vital component in a complex web of interactions. Without it, the whole ecosystem may fall. If you didn’t know this, you might think that losing the Great Tit from a forest wouldn’t matter – after all, there are plenty of similar-looking small songbirds that will perform the same role. But look closer at their beaks, and you’ll see they’re all different. The Great Tit, with its thin, needle-like bill, eats insects – whereas a species like the Hawfinch Coccothraustes coccothraustes, with its thick, strong beak, prefers to crack tough seeds. Lose the Great Tit, and you could face a swarm of insect pests. Lose the Hawfinch, and you could halt seed dispersal across the entire landscape.

Image credit: © Ondrej Prosicky / Shutterstock

Understanding birds’ bodies can also explain why certain threats affect birds differently, even if they eat exactly the same food. Because of the different ways they digest food, owls can get all the nutrients they need even in polluted habitats, whereas diurnal raptors such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus cannot. This could be one of the reasons raptor populations have plummeted in degraded forests.

By now, you’re probably eager to find out more about the amazing inner lives of the birds you see. Fortunately, the Avian Ecomorphological Project can do just that. Organised by the Biosphere Science Foundation, this global initiative aims to show birds to the public as they’ve never seen them before, discovering and communicating the fascinating explanations behind bird’s unique anatomies. Workshops and lectures across Europe have already proven hugely popular. Now, they want to spread the fascination to an even larger audience.

One of their key visions is to create an Avian Ecomorphological Atlas, which will illustrate and explain physical traits found throughout the avian kingdom. Rather than categorising birds into groups of closely-related species, like most bird books do, this visual feast will compare fascinating cases of convergent evolution, whereby very different birds have evolved similar adaptations to tackle similar problems. For example, hummingbirds and woodpeckers both possess grooves in their skulls to accommodate their extremely long tongues, which they use to drink nectar or extract insects. Such a comprehensive round-up of birds’ anatomical features has never been done before.

Prepare to discover the answers to many mysteries of the bird world – why do owls’ feathers glow pink under UV light? Why do cranes and other waterbirds have extra-long windpipes that bend around in loops? The team plans to demonstrate not only what they have discovered, but also how they discovered it – which is often just as fascinating. They will work with museums, zoos and bird rescue centres to study anatomical samples. Photos and videos that were taken to capture birds’ beauty will be scrutinised for important information about their physiology or behaviour.

These discoveries will not only engage the public, but also directly support conservation action. By bringing together hard, visual evidence of physical threats like plastics or pollution, they can attract the attention of conservationists and authorities.

The project is seeking collaboration with funders and partners who can help them to disseminate their message through social media, TV and radio, building on the success of similar documentaries such as BBC’s “The Life of Birds” with David Attenborough. Perhaps one day, everyone will be able to see beyond the beautiful plumage to the incredible evolutionary masterpiece that birds truly are.

Related news

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.