Alive as a kestrel: An emblem for preventing extinctions

To celebrate endangered species day, we’re introducing the anti-Dodo: Mauritius Kestrel. The official national bird of Mauritius, it is one of the world’s greatest conservation success stories, making the island nation and its BirdLife Partner iconic for preventing extinctions, rather than extinction.

By Shaun Hurrell

Header image taken by MWF / Jacques de Spéville

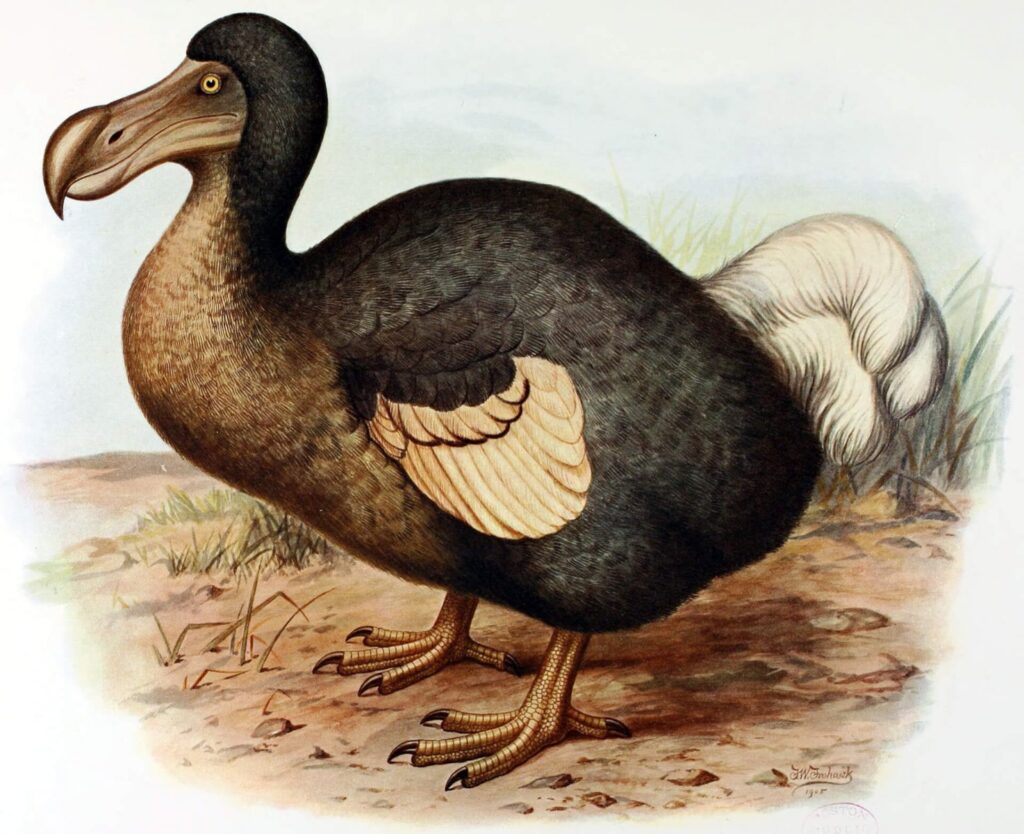

“Dodos are everywhere! On our coins and banknotes, the Mauritian coat of arms. There are fluffy Dodo mascots, Dodo cafés, even Dodo flip-flops,” exclaims Jean Hugues Gardenne, Communications Manager for the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF, BirdLife Partner). “They’ve become our de facto national bird. But there’s a real irony to Mauritians reiterating such a sad story of extinction.”

It’s not hard to see why the Mauritian people could have attached themselves to a disheartening environmental narrative, though. Dutch sailors first started decimating the Mauritian island habitats in the 1600s when they colonised the unique archipelago in the Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar, and now only 1.3% of good-quality native forest remains. The poor old flightless, ground-nesting Dodo epitomises this hapless human plundering of the innocent, having not evolved defences to the flurry of introduced mammalian predators that ensued – Homo sapiens included. The last Dodo was reported dead in the 1680s, and many other species followed, but the legend of the Dodo has lived on worldwide.

However, there’s another side to the Mauritian environmental story: one of hope, dedication and conservation success. A story that’s now captivating the hearts of the Mauritian people, including their government. This story is centred on another bird – just as emblematic, but living.

Most threatened in the world

A rush of air. A flash of russet. An agile falcon with pointed wings and a long tail darts through the leaves. She then soars above the trees and comes properly into focus, perching daintily on a familiar vantage point. Introducing the Republic of Mauritius’ official National Bird: Mauritius Kestrel. Once the most threatened bird in the world, the species can now be seen quite easily on an ecotourism excursion.

“It was amateur ornithologists – the ‘early guardians’ – who first noticed the disappearance of Mauritius Kestrel in the 1960s,” says Vikash Tatayah, MWF’s Conservation Director, “including Mauritians such as dentist and painter France Staub, entomologist Jean Vinson and Yousouf Mungroo.” But despite initial attempts to save it in the 1970s, by 1974 it was down to only four confirmed individuals (including just one breeding pair). Mauritius Kestrel seemed doomed to extinction, just like other Mauritian birds of prey (the country’s endemic owl species went extinct in the 1800s).

“We might abandon the Mauritius Kestrel to its all-but inevitable fate,” wrote environmentalist Dr Norman Myers in The Sinking Ark (1979), “and utilize the funds to proffer stronger support for any of the hundreds of threatened bird species that are more likely to survive.” But a small team in Mauritius refused to sit by and watch the kestrel disappear.

Threats to the species were, in part, similar to the Dodo’s: the clearing and degradation of the kestrel’s forest habitat – along with its prey of geckos and small birds – was devastating to its population. So was the impact of introduced mammals: rats and monkeys that crept into the birds’ cliff-top crevices and tree-cavity nests, or cats and mongooses that killed fledglings on the ground. But unlike with the Dodo, the widespread use of the pesticide DDT after the Second World War added to the kestrel population’s collapse (in the case of its eggs, quite literally – in 1967 DDT was found to cause eggshell thinning).

Drastic action was needed. Despite the doubts and the desperate odds, a renewed and concerted effort was launched to save the kestrel in the 1980s, driven passionately by a nascent MWF, working with the Mauritian government and international conservation organisations. Now, dubbed ‘a conservation marvel’ and well known in the conservation sector, the kestrel’s population has swelled to the hundreds and has inspired the successful recovery of other Mauritian species including Pink Pigeon, Echo Parakeet, Mauritius Fody [see below] and several reptiles.

Egg harvesting and wild camping

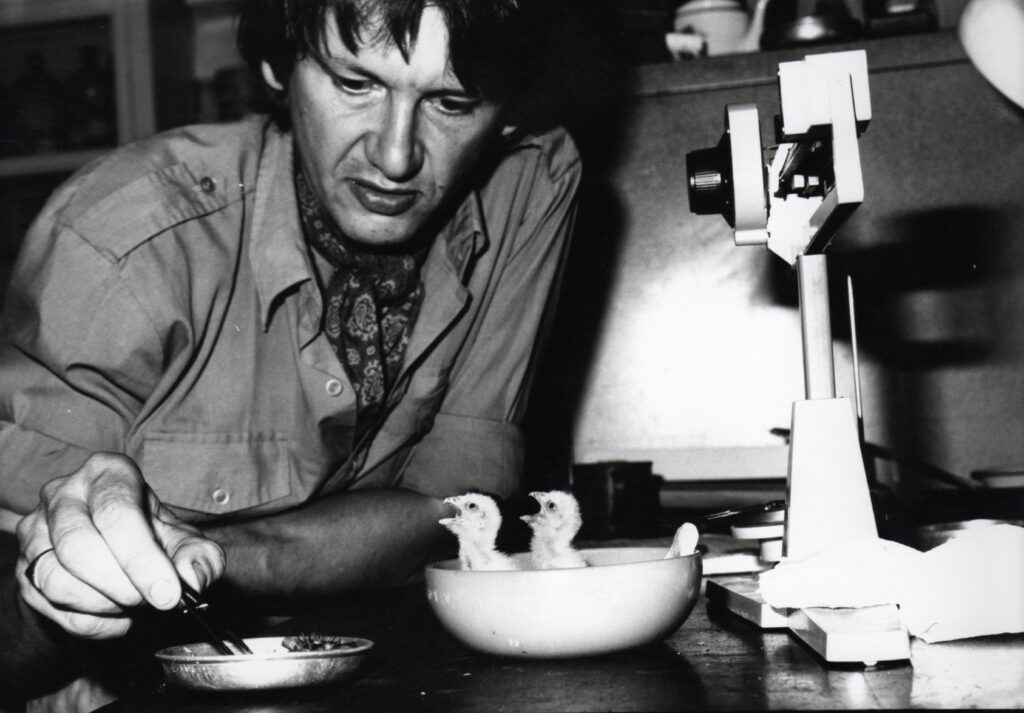

But it wasn’t easy. It took a novel, ‘cavalier’ approach led by 2016 Indianapolis Prize-winner Professor Carl Jones (who arrived in 1979), based on captive breeding and supplementary feeding, together with management of nests in the wild.

Eggs were harvested from the last wild pairs, then artificially incubated and the young hand-reared using techniques adapted from falconry (including hand puppets). With enough food, females will lay a second clutch of eggs when the first is taken (so-called ‘double-clutching’), helping to boost numbers.

Captive-bred and reared birds were introduced to the wild, protected and nurtured. Kestrels were even habituated to a whistle and would swoop down at feeding time: “That split second when it grabs food from your hand is beyond words,” says Tatayah. Over 300 birds were reintroduced over a decade into the Black River Gorges in the west and the Bambou Mountains in the east of Mauritius.

But there’s little point in reintroducing a species to a degraded and dangerous environment. Intensive monitoring and protection was needed to fully understand the species, its needs and immediate threats. Jones, Lewis and other researchers would ‘become a kestrel’ to find solutions, wild camping under nests for days on end. “Adults often attacked our heads during nest inspections – bald men must take extra care,” laughs Tatayah.

It was nights like that when the team realised the threat of introduced monkeys, cats and mongooses, and the solution: predator-proof artificial nest boxes that kept chicks out of reach of Long-tailed Macaques in particular. Wild kestrels have also been proven to lay more eggs and rear chicks more successfully in these boxes.

MWF also began the immense task of restoring lost and degraded forest to increase the habitat for the kestrel and other species. “We are fighting against the odds,” says Tatayah, “overcoming four centuries of human presence and disturbance on the environment, which in itself is a big challenge.” To make matters worse, introduced plant species – such as Strawberry Guava – were also spreading into native forest, killing off seedlings of native plants and reducing the food supplies and hunting efficiency of the kestrel.

Turning point

The declaration of Black River Gorges as Mauritius’ first National Park in 1994 was a turning point in both kestrel conservation and the environmental consciousness of the nation. MWF had previously invited the late Prime Minister of Mauritius, Sir Anerood Jugnauth, to visit the area and feed a few wild birds. He was inspired and drew reference to the kestrel and the wonderful work that had been done in its conservation when debating the need for the national park. The kestrel is therefore also a high-flying example of how the conservation of one ‘umbrella species’ (and also top predator) can lead to the protection of an entire ecosystem. Moreover, the spraying of DDT for agriculture and to repel mosquitoes was drastically reduced from the 1980s, though it continued to be used in some localised outbreaks of malaria and chikungunya virus.

By the early 2000s, the kestrel’s population had increased to a high of 500-600 and was reclassified by BirdLife as Vulnerable on the Red List of threatened species. However, while the kestrels on the east coast continued to thrive, reports came of a population decline in the Black River Gorges in the west. This was, ironically, just after MWF and collaborators had stopped actively monitoring and providing nest boxes in the west sub-population because the kestrels seemed to be doing so well on their own (and to some extent due to funding constraints – which goes to show what happens when conservation funding is taken away).

As a result, the kestrel was ‘uplisted’ to Endangered again in 2014 because of its small and declining population (currently around 350 wild birds). A recent research paper looking at the long-term trends of four introduced populations of Mauritius Kestrel confirms the importance of post-release monitoring, which MWF did manage to rectify hastily.

National pride

“We want Mauritians to be proud of saving species,” says Hugues Gardenne. “Go back 10 years and the average Mauritian was not concerned about protecting nature. But now, with the impacts of climate change visible and more awareness of our iconic species, people are becoming more and more environmentally aware.”

In total, Mauritius has prevented the possible or probable extinction of nine animal species: five birds, three reptiles and a fruit bat. It is now recognised as saving more species from extinction than any other country. With Mauritius Kestrel the driver of this work and the bird proudly displayed on its logo, MWF is showing the way forward with its innovative conservation approaches. The organisation has also saved over 100 endemic plants on Mauritius and neighbouring Rodrigues Island and on offshore islets, and countless endemic insects along with them. “We want all Mauritians to know this,” says Hugues Gardenne, who has been hastily disseminating thousands of leaflets on the kestrel and wider conservation efforts to the Mauritian public following the announcement of their new National Bird.

Jones put forward the idea of Mauritius Kestrel as a national bird a decade ago, and Tatayah was applauded and cheered when he presented the idea to Members of Parliament, including Senior Ministers in late 2021. The ratification was carried out quickly so that the announcement could be made on 12 March last year, the 30th anniversary of the accession of Mauritius to the status of Republic (which followed independence from the British Empire). Raptors feature as the national birds of many countries, aptly representing beauty, proud independence, strength, majesty, survivorship and determination.

Not ‘as dead as a Dodo’

“The restoration of the Mauritius Kestrel has been an international effort and demonstrates what can be achieved if we co-operate,” says Jones. Since its creation and then status as a BirdLife Partner in 1984, MWF has grown stronger and stronger as an independent NGO, with support from around the world, including BirdLife*. “The greatest joy has been to see the development of local expertise – work that was once largely done by expatriate ornithologists is now being conducted by a growing group of young Mauritians,” he adds.

The work on the kestrel will have to be carefully managed for the foreseeable future. “The National Bird is not just a name,” says Tatayah. “We want it to drive conservation here. Mauritius cannot look back on the kestrel, its forests, plants and geckos on which it depends.” MWF staff continue their work to restore and protect kestrel habitat from destruction and degradation, and are confident the species can recover well in the west with the help of more nest boxes and additional releases. MWF also maintains a productive working relationship with its main partner, the National Parks and Conservation Service, especially in captive rearing and releases into the Black River Gorges National Park. “By declaring the National Bird,” says Jones, “the Government of Mauritius is recognising its value and making a commitment.”

“Any species can be saved,” says Roger Safford, BirdLife’s Preventing Extinctions Programme Manager, ex-MWF employee and co-author of Birds of Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands. “We just have to try harder. There are no lost causes.” Tatayah, Jones and Hugues Gardenne couldn’t agree more, seeing a future where Mauritius is famous worldwide not for the Dodo’s extinction, but for preventing extinctions.

“The success story of the

Mauritian Kestrel restoration is

proof of the power of

collaboration and of BirdLife

International’s approach to

delivering meaningful impact by

bringing together scientists,

partners and national champions.

These outcomes are often hard

fought, they require patience,

skill and teamwork but that is

what BirdLife is all about. I

consider it a privilege to sit on the

International Advisory Group and,

as a Mauritian, I am delighted

along with many others to have

supported the kestrel project.”Nathalie Boulle, member of BirdLife’s International Advisory Group

Three other bird species saved from extinction in Mauritius

Pink Pigeon (Vulnerable)

From just nine birds up to 473 by 2019, Pink Pigeon could well have gone the way of its extinct endemic pigeon cousins, the Dodo and Reunion Pigeon, were it not for the devotion of MWF.

Echo Parakeet (Vulnerable)

From 12 birds in the 1970s to over 750 in 2020 when it was reclassified as Vulnerable, the recovery of Echo Parakeet is testament to MWF’s conservation techniques.

Mauritius Fody (Endangered)

After a similar story of drastic declines and MWF’s response, the population of Mauritius Fody stabilised in the 1990s, then increased following reintroduction to a predator-free islet.

Mauritian Wildlife Foundation

would especially like to thank:

National Parks and Conservation

Service and Forestry Service

(Government of Mauritius),

Standard Bank, Adna Global,

Ferney Ltd, Zoological Society of

London (UK), Natural History

Museum (UK), University of

Reading (UK) and The Peregrine

Fund (US).