Common Cause

Range-restricted, rare and threatened species understandably attract much conservation attention, but more familiar, numerous and widespread birds are no less crucial to biodiversity. The concept of ‘keeping common birds common’ has therefore long been an important part of BirdLife’s work.

By John Fanshawe

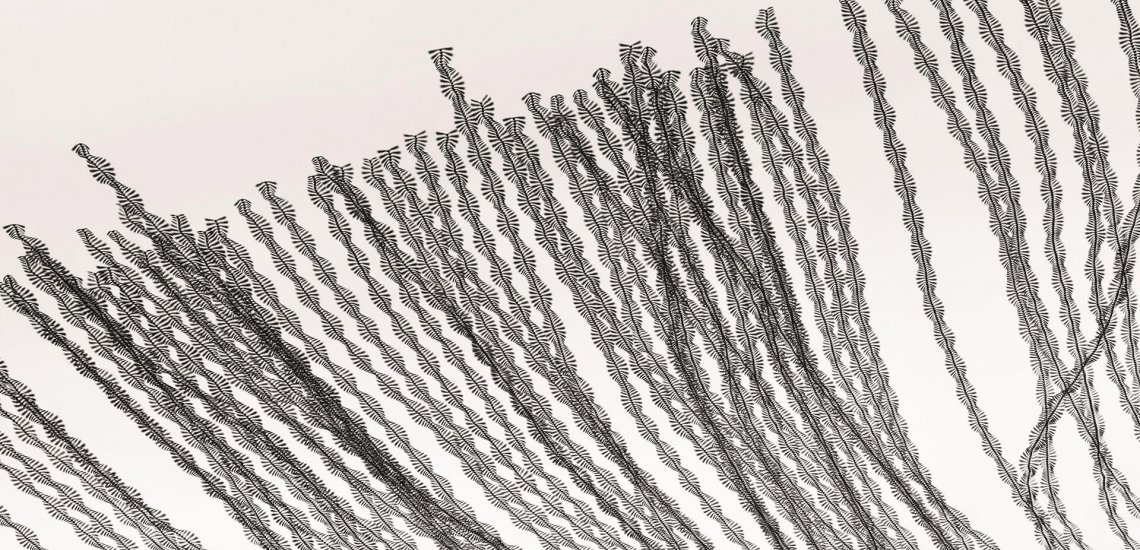

Header Images: Common Starlings may look abundant during a murmuration, but this species is declining across Eurasia © Eleanor Hamilton

Inevitably, as custodians of the IUCN Red List, BirdLife’s work is often dominated by questions of scarcity and loss, and the success of our Preventing Extinctions Programme is rightly celebrated.

Many species have been brought back from the edge of extinction, and some have become celebrated success stories. Take Seychelles Warbler, for example, with numbers recovering from 29 individuals on Cousin Island in 1969 to more than 3,000 birds spread across five islands today, and with birds now translocated and breeding on Cousine, Aride, Denis and Frégate.

For a highly restricted island endemic, this cousin of the widespread Common Reed- warbler is edging towards safety, and it is now treated as Near Threatened. This is just one step away from Least Concern, the IUCN threat category that, in many respects, is closest in equivalence to ‘commonplace’.

Everyday birds

But what does ‘common’ mean to us? Sitting with friends in a café in Pittsburgh, USA – city of steel and of Andy Warhol – I am surrounded by Common Starlings, a mix of adults and younger birds, the brown plumage of the latter pockmarked with the first signs of the iridescence that sets them ablaze in any setting sun.

In 1758, when the great Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus first described the species to science, he coined the binomial Sturnus vulgaris, with a specific name derived from the Latin word vulgus, meaning a multitude, uncountable, a throng. Implicit in his naming was a sense of how widespread and familiar starlings were to people across their Eurasian range.

This was not the case in the USA, however, where the bird is an alien invader and now an abundant pest. Its presence is the result of an ill-judged introduction by the American Acclimatization Society, associated with Eugene Schiefflin’s reputed plan in the 1890s to introduce all the species mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare to the Americas. BirdLife’s distribution map of Common Starling reveals that the species has spread across most of the continent, a range for which the Cornell Lab of Ornithology estimates a population of more than 200 million birds.

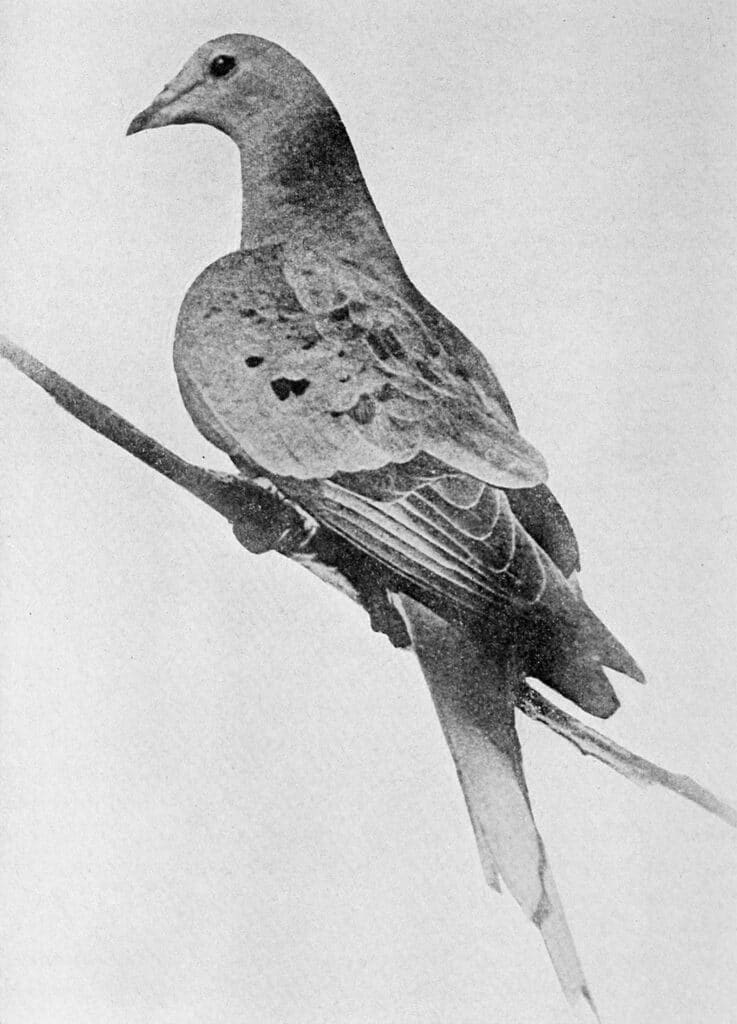

More than half a century before, John James Audubon had started to publish his revolutionary Birds of America (1827-1838), printing the 435 plates in Edinburgh and London. Of the birds Audubon illustrated, one of the most lauded is the now extinct Passenger Pigeon. Writing in 1947, Aldo Leopold argued it was “a biological storm … the lightning that played between two biotic poles of intolerable intensity, the fat of the land and his own zest for living. Yearly the feathered tempest roared up, down, and across the continent, sucking up the laden fruits of forest and prairie, burning them in a travelling blast of life. Like any other chain reaction, the pigeon could survive no diminution of his own furious intensity. Once the pigeoners had subtracted from his numbers, and once the settlers had chopped gaps in the continuity of his fuel, his flame guttered out with hardly a sputter or even a wisp of smoke.”

With its vivid mix of awe and wonder, and its undercurrent of the precarity of tipping points, this account seems to foreshadow much of our contemporary conservation crisis.

In the language of an IUCN Red List Assessment, Passenger Pigeon would have moved in the course of a little over 50 years from Least Concern (LC) to Near Threatened (NT) through Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN) and Critically Endangered (CR) to Extinct in the Wild (EW) and finally Extinct (EX). The last captive bird, Martha, died in Cincinnati Zoo, Ohio, in 1914 – a grim escalator of disappearance that would have seemed impossible to those who saw the immense, seemingly endless pigeon flocks at their most numerous.

Even in 1878, when the last communal nesting occurred in Michigan, 50,000 birds were being killed a day. It is still, perhaps, the most extreme example of a species shifting from common to lost, and it seems inconceivable that birds could – in today’s conservation climate – suffer a similar fate.

Grim Reality

Or is it? Even in the last 30 years, the collapse of some Asian vulture populations has provided grim statistics. Slender-billed, White-rumped and Indian Vulture numbers crashed as a result of poisoning by the veterinary drug, diclofenac, and these species accelerated from LC in the 1980s to CR in 2000 as populations fell by more than 99 per cent.

For older Indian citizens, memories of these species as commonplace are still extant, but for anyone born after the millennium, they are gone. It is an acute example of the so-called ‘Shifting Baseline Syndrome’, when young people in each generation simply accept the nature around them as normal, and cannot – for obvious reasons – remember times of species abundance.

People’s understanding of a depauperate nature declines year after year after year. These declines can be insidious, and risk being unseen. Leopold wrote that “one of the penalties of ecological education is that it lives alone in a world of wounds,” arguing that “much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen”. Across BirdLife, we see these changes as familiar, common birds bleed from the landscapes and seascapes that surround us.

Returning to Common Starling, the British Trust for Ornithology notes that the species has been on the UK Red List since 2009, and that numbers visiting gardens across the country declined by 27 per cent between 1995 and 2021. For me, such declines in our garden birds are epitomised by Spotted Flycatcher, which has declined by 86 per cent in Britain and Ireland since 1970. With huge fondness, I recall my father lifting me up to see into a ‘Spot Fly’ nest as a child, and I always marvelled at their annual returns to create a few weeks of balletic mayhem as they dashed, hawked and endlessly harried the flying insects around our house.

Despite the massive declines that Common Starling and Spotted Flycatcher have undergone, they are, by reason of large ranges, treated as LC.

Growing Concern

Buried in these crashes are many of the reasons common birds matter so much, and why, as a community of conservationists, we cannot ignore them. Catastrophic examples of loss, like the Asian vulture crisis (or the Passenger Pigeon) can, and will, happen again. But all around us familiar species are at risk. Indeed, the Red List empathises that “LC simply means that, in terms of extinction risk, these species are of lesser concern than species in other categories. It does not imply that these species are of no conservation concern.”

So, species broadly considered common, commoner or LC, which represent just over three-quarters (76.1 per cent) of all 11,162 recognised species worldwide, are, at the very least, candidate threatened species. But they are also essentially the birds that are most familiar to people, the birds of daily encounter. We see and hear them, consciously and unconsciously, and evidence mounts that they are central to our sanity and well-being.

Deeply entrenched in human cultures worldwide, birds suffuse our language and literature, our dance and music, and flood across popular culture like a feathered tide. The word ‘auspicious’ has its origins in the Latin aupicium, divination from watching birds, and the growing popularity of citizen science, with digital platforms like eBird, BirdLasser and BirdTrack, is enabling bird monitoring or contemporary ‘divination’ on a colossal scale worldwide.

On 14 May 2022, eBird’s Global Big Day saw 51,455 birders submit 132,350 checklists and record 7,673 bird species – a world record, but also a demonstration of what common birds really mean to us, wherever they are found.

Threats and pressures

Common birds invariably face similar problems to rarer and localised species, although larger ranges and numbers mean declines can be harder to spot. Long-term monitoring methods, including key common bird indices, patch birding, constant-effort ringing and citizen science, are vital in identifying local trends and analysing them at national and international levels. An objective in BirdLife’s new strategy reflects this: “To promote and deliver species and site monitoring systems through effective local citizen science and develop indices for key species groups.” This will help the Partnership flag up common birds at risk. People care for these birds and about losing them and the soundscapes they create.

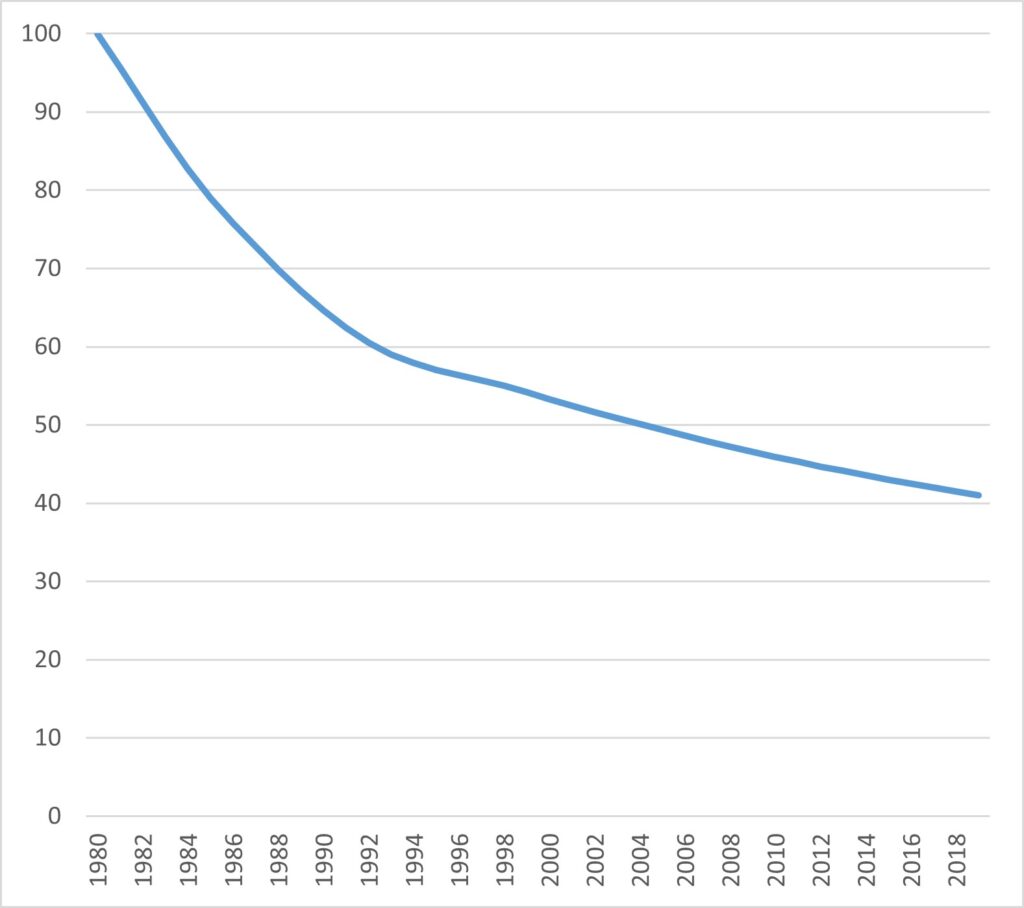

The EU common farmland birds indicator for 1980-2019 combines the population trends of 39 species, some of which are increasing but most of which are in decline, to produce an overall indicator for the 40-year period.

Birds and Human Culture

In 2009, BirdLife published Birds and People: Bonds in a Timeless Journey, with a text by Nigel Collar that explored the rich interplay between nature and culture, a trend that has continued to gain momentum. A second Birds and People appeared in 2013, this time written by Mark Cocker and illustrated by photographer David Tipling. As well as the author’s deep scholarship, this tome included 650 contributors from 81 countries, many of them friends and collaborators from within BirdLife.

Flight from Grace by Richard Pope, Avian Illuminations by Boria Sax and Birds and Us by Tim Birkhead have all been published in 2022, and again demonstrate our appetite for understanding the complex interwoven lives of birds and people, not least as they invade our imaginations. We lark about, speak of our leaders as hawks and doves, choose birds as national symbols, for our stamps and coins, and embed them in our place names.

Across the world, sports teams bear their names – the Toronto Blue Jays, the Pittsburgh Penguins, the Norwich Canaries – and, of course, we adopt them across an array of commercial logos, including Twitter’s singing blue bird.

This article originally featured in the July-September 2022 edition of the BirdLife magazine. Find out how you can subscribe here.