Taking action for albatrosses

Two-thirds of the world's albatross species are globally threatened because of human action, with up to 100,000 birds killed annually as bycatch. Fortunately, BirdLife and partners are turning the tide on albatross extinction.

By James Lowen

Imagine savouring a sumptuous fish dish in a classy restaurant. Mmm! It tastes lip-smackingly good. Suddenly – unexpectedly, traumatically – one bite changes everything. Swallowing the next mouthful lodges a bone in your gullet. You splutter, choke and turn crimson. Fortunately, a quick-thinking companion performs the Heimlich manoeuvre. Ejecting the bone from your throat, she saves you from an untimely demise.

Now replay the scene, with one difference. Replace the bone with a 5-cm-long steel hook. The barb wedges so firmly in your oesophagus that no friend can save you. Death is inevitable.

Now imagine you are an albatross, riding the waves, seeking fish. You chance upon a longline- fishing vessel; from experience, this means food. You spy a tempting morsel flying into the water. For the fisherman: bait. For you: an easy meal. Eager to eat, you fail to discern the barb piercing the bait. You become impaled. As the fisherman releases the weighted, hook-tipped line, it sinks, taking you with it. You drown.

As an isolated occurrence, this would be tragic. For years, however, albatrosses have died through interactions with fisheries every five minutes.

Thankfully, though, through the Albatross Task Force (ATF) and its wider Marine Programme, BirdLife is turning the tide on albatross bycatch.

Header Image: Wandering Albatrosses have a 3.5 metre wingspan, the longest of any bird species © fveronesi1

RECORD-BREAKERS

US conservationist Robert Cushman Murphy once wrote: “I now belong to a higher cult of mortals for I have seen the albatross.” His message was clear: albatrosses are special. We revere them for being record-breakers. Wandering Albatross has longer wings than any living bird. Wisdom, a Laysan Albatross, is the oldest-ever wild bird. We also admire their fidelity and unstinting parental devotion. Above all, their free-ranging lifestyle resonates. Satellite telemetry has tracked one ‘Wanderer’ covering 25,000 km in nine weeks. A Grey-headed Albatross circumnavigated the globe in just 46 days.

As seafaring nomads for nine-tenths of their life, albatrosses symbolise unfettered freedom. Yet it is precisely this liberated lifestyle, combined with ecological traits including slow sexual maturation and reproduction, that has engendered their precipitous downfall – and makes their conservation so challenging.

It is barely 30 years since unequivocal, large-scale evidence emerged of an albatross crisis: around 40,000 Shy Albatrosses were being killed accidentally in Japanese fisheries operating off Tasmania. Although the diverse, remote nature of many fisheries made quantification difficult, research deepened our understanding of the problem’s intensity and geographical reach. It became clear that bycatch was unsustainable for many seabirds. Together with other pressures they faced, from ingestion of plastic debris to rodents eating chicks, this was a recipe for disaster.

In 2005, the year the ATF was established, 19 of the world’s then 21 albatross species were considered globally threatened. The figure is now 15 species (of 22, following taxonomic change), plus six Near Threatened, with two Critically Endangered and seven Endangered. As a group, only parrots may be more threatened than albatrosses.

The reason boils down to a juxtaposition of birds and people. Some of the ocean’s richest industrial fishing grounds are also key foraging areas for seabirds. Albatrosses naturally feed opportunistically on squid and fish on the surface, smelling their quarry from great distances. They come into conflict with fisheries when foraging similarly behind vessels, “attracted” – says BirdLife South Africa’s Andrea Angel – “by bait put out by some vessels and by discards of unwanted fish”. Many become snared on baited longline hooks and drown, or fatally strike trawl cables towing nets.

Such ongoing, ostensibly avoidable mortality in rapidly declining avian icons was always going to galvanise BirdLife. Its Marine Programme is now approaching its 25th anniversary. It instigated the ATF which, says Rory Crawford, BirdLife International Bycatch Programme Manager, “has been the beating heart of our work to turn around albatross declines”.

MISSION POSSIBLE

The ATF’s mission involves slashing seabird bycatch by 80 per cent in target fisheries off South America and southern Africa. Because albatrosses roam widely – those occurring off South Africa, for example, include birds breeding as far apart as the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and New Zealand – the ATF is a truly international team. The first group of bycatch-prevention experts was established in South Africa, followed by Brazil and Chile, with coverage subsequently expanded to cover Namibia, Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador and Peru.

ATF instructors work alongside governments, communities and fishing crews onshore and aboard commercial vessels. Their fundamental responsibility is to demonstrate simple, effective ways to spare the lives of albatrosses and other seabirds. The idea is that fishing crews adopt best-practice techniques and, ideally, that governments mandate suitable solutions and monitor their roll-out.

Measures are tailored to each fishery, but none are expensive or complicated. Longlines can be set at night, when seabirds are less active and thus less likely to be snared. Adding weights to lines sinks hooks more rapidly out of seabirds’ reach. Colourful bird-scaring lines frighten birds from the danger zone, reducing collisions with cables and attacks on baited hooks. “This simple measure,” Andrea says, “reduced bycatch off South Africa from an estimated 10,000 birds every single year to less than 200.”

“Our main goal,” says Andrea’s colleague Reason Nyengera, “is to try and win fishermen’s hearts,” converting them to albatross-friendly practices.

And the ATF wins minds too, because minimising bycatch makes financial sense. Removing dead birds from hooks and nets is a poor use of crew time, while bait loss may reduce the number of fish caught. One study of a small Argentine fishery suggested that bird-scaring lines could save $1-2 million over 10 years. In Chile, the ATF trialled a new kind of purse-seine net that not only reduced bycatch by 98 per cent, but – using 800 kg less mesh – saved $3,000 per vessel.

Alongside the ATF’s work with national fisheries, BirdLife’s Marine Programme has long strived to reduce bycatch on the high seas, where its research recently revealed that albatrosses and large petrels spend 39 per cent of their time.

These waters are governed internationally, including by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations. “In 2021,” Rory Crawford says, “former ATF Brazil instructor Dimas Gianuca became our very first High Seas Bycatch Specialist, supporting mitigation trials on Asian distant-water tuna vessels.”

Meanwhile, a new venture with Global Fishing Watch involves testing advanced technology that may identify illegal or unregulated fishing activity. “Electronic monitoring of bycatch is very much the future,” Rory explains, “and we’re supporting or leading trials in Argentina, Chile and South Africa.”

Advocacy is also key to saving albatrosses far from shores. Alongside partners in the High Sea Alliance, BirdLife is pressing the world’s governments to conclude agreement on a strong United Nations treaty to protect high seas areas such as the Emperor Seamounts in the Pacific, where Laysan Albatross and Black-footed Albatross gather to feed. A suitable convention is the missing link for effective conservation of marine biodiversity.

WINNING AGAINST THE ODDS

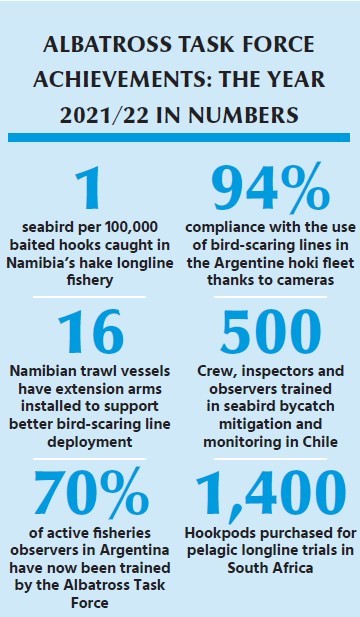

This hive of activity is all very well, but does it work? The short answer is: yes, and spectacularly so. “Hard-won successes over the previous decade have led to fleet-wide changes in fishing practices,” Rory judges, “so our efforts have transitioned to strengthening compliance with highly effective mitigation measures.”

Various compelling sets of numbers underpin this assertion. Most notably, South Africa’s demersal trawl fishery has seen a remarkable 99 per cent drop in albatross deaths since the ATF started work in 2006. “It’s a tiny team here,” Andrea says, “and I’m very proud that we’ve achieved a lot.”

In adjacent Namibian longline fisheries, ATF endeavours and consequent government regulation mean that 20,000 fewer seabirds (notably the Endangered Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross) now die annually – a 98 per cent reduction in bycatch. With appropriate government investment and support, the Namibia Nature Foundation (which is part of the ATF) hopes that low levels of bycatch can be sustained long into the future.

The ATF is now targeting 90 per cent reductions in fisheries in Argentina and Chile. Early signs are positive. In Argentine trawl fisheries, introducing bird-scaring lines has reduced the number of Black-browed Albatross collisions from almost 17 birds per hour to under three. The introduction of monitoring cameras has also tripled ship compliance in just two years.

Cultural change is also underway. Roberto Galarza, a fisherman for Estremar SA, told Aves Argentinas (BirdLife Partner) that “it is important to use bird-scaring lines so that there are fewer dead albatrosses. If education continues, their use will become habitual.”

There are wider Marine Programme successes too. Following BirdLife influencing, all five ‘tuna commissions’ now require seabird-bycatch mitigation measures for vessels. Nine out of the top 10 ATF hotspot fisheries for seabird bycatch have set regulations to protect seabirds.

This all bodes well. Whether by working at the sharp end of conservation aboard fishing vessels, lobbying national governments or tracking seabirds over the waves, BirdLife “has saved thousands of albatrosses from an untimely death and shown that seabird bycatch is a solvable problem,” Rory says.

Even so, albatrosses are still being killed. To respond, “the ATF needs to double down at what we do best, extending work to new fisheries, providing practical knowledge, capacity building and research to keep seabirds off hooks, away from cables and out of nets,” Rory concludes. “Without continued support, we wouldn’t be able to keep up the fight to save albatrosses.”