It worked! Rare birds recovering thanks to ambitious island restoration

It was the most ambitious and logistically challenging island restoration project to date. The aim in 2015: to turn some of the world’s rarest birds back from a path to extinction by removing introduced predators from remote French Polynesian islands. Now the birds are truly bouncing back, giving hope for future restorations.

Marcela Bellettini, BirdLife Pacific

Out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, there is a group of islands that host some of the most beautiful and unique birds in the world. The Acteon and Gambier Archipelago, part of French Polynesia, lies approximately 1,600 km from Tahiti, the nation’s political centre. Boasting some of the highest numbers of endemic birds in the tropical Pacific, this far-off piece of paradise is a nature-lover’s dream.

Sadly, even these remote islands have not escaped human interference. Like numerous islands in the Pacific, for many years they were under severe threat from introduced species. From predators including rats to aggressive tangles of non-native vegetation, havoc was wrought on these delicately balanced coral atoll and volcanic ecosystems.

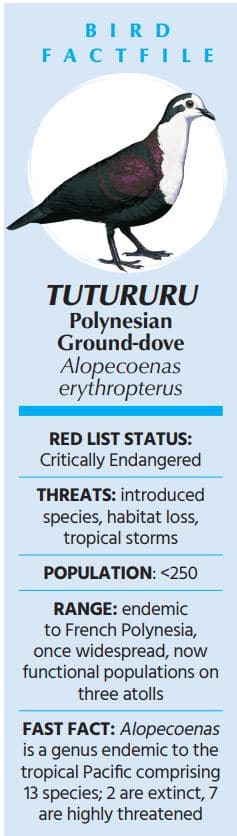

For the islands’ birds, it is a life or death situation. In the Pacific, up to two thirds of all bird extinctions are directly linked to the introduction of alien species. For some of the rarest birds in the world – like Tutururu, or Polynesian Ground-dove Alopecoenas erythropterus (Critically Endangered), and Titi, or Tuamotu Sandpiper Prosobonia parvirostris (Endangered), that evolved in the absence of mammalian predators – time was running out.

In 2015, BirdLife, SOP Manu (BirdLife in French Polynesia) and Island Conservation took on their most ambitious conservation project ever: the challenge of restoring the habitat and removing introduced species from six islands (Vahanga, Tenania, Temoe, Kamaka, Makaroa and Manui), thereby securing a future for four threatened bird species and many others.

‘Operation Restoration,’ as it was dubbed, was not without its difficulties. Getting 200 tonnes of equipment shipped to these remote islands required diligent logistics, 165 helicopter hours, more than two years of planning and a team of 31 people across three continents to deliver the operation. If that doesn’t sound hard enough, the prospect of adverse weather conditions, sleep deprivation, sharks, seasickness, tropical sores, clouds of flies and a castaway’s diet would make any sane person turn their boat around and sail straight back to the idyllic island of Tahiti.

Despite all of this, the team were not fazed and, if anything, it just added to the adventure. Over the following two months, the operation was rolled out over the six islands, working alongside local communities throughout. An immense amount of human power was needed in particular to remove the invasive tangles of the Lantana plant, but blood and sweat was well spent in the knowledge that many native plant species would recover and allow the fruit- and seed-eating birds to thrive again.

Despite the operation having gone to plan, proof of success would not be known for another few years, and so they left the island chain tired but with immense hope for the recovery to come. A follow-up survey in 2017 revealed that the team was successful in eliminating invasive species from five out of the six islands – a ground-breaking 1,200 hectares in total – and there were early promising signs of the recovery. Five years on, in November 2020, SOP Manu and BirdLife were able to return and capture a snapshot of the islands and their species’ recovery.

Saved from extinction

Prior to the operation, the once-widespread Polynesian Ground-dove persisted as a single functional population on their only remaining predator-free island, Tenararo. As of 2020, there are now three flourishing populations all on restored islands. The few that previously remained on Vahanga have since doubled, and on the neighbouring Tenania atoll they have re-established a secure and permanent presence for the first time in hundreds of years.

Tuamotu Sandpiper, another endemic, and an ancient cohort of migratory sandpipers that have lost their migratory ability, is making a slower but steady comeback. The population in Vahanga has not increased significantly and is also yet to establish on Tenania. Nonetheless, with over a thousand Tuamotu Sandpipers on Tenararo, they remain the most numerous species there.

Then there’s the Koko, or Atoll Fruit-dove Ptilinopus coralensis (Near Threatened). Needing no search, their soft coos clearly audible and a constant flash of yellow and red hues visible to everyone, these now abundant birds dart through the lush foliage.

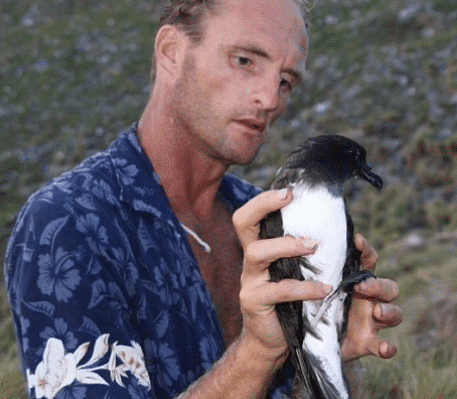

In addition to land birds, the islands provide critical habitat for nineteen species of seabird, and the changes being witnessed here are no less than inspiring. Since 2015, five new seabird populations have established on three of the islands, including Christmas Shearwater Puffinus nativitatis on two islands, whilst Tropical Shearwater Puffinus bailloni, Red-tailed Tropicbird Phaethon rubricauda and Black Noddy Anous minutus all inhabit one each.

In a further affirmation of the recovery, nesting Polynesian Storm-petrels Nesofregetta fuliginosa (Endangered) have increased year on year and by more than 100% of their estimated 2015 population. Murphy’s Petrel Pterodroma ultima is another species signalling its intent to reclaim these islands from its stronghold of a thousand pairs on Temoe, to gradually increasing numbers on Vahanga and prospecting a return to Tenania.

The isolation and expense of accessing these islands means the monitoring is limited, but “The changes taking place are apparent, particularly the avian comeback”, says Tehani Withers (SOP Manu’s Restoration Manager). “Given that five years of recovery is barely a ripple in the prior hundreds of years of harm, it’s deeply satisfying to see such a vibrant transformation.”

“This restoration success has demonstrated that carefully planned and well-executed operations across multiple remote islands can provide significant benefits for the biodiversity and local community simultaneously,” says Steve Cranwell, BirdLife’s invasive species expert, who headed up the operation.

“The five restored islands of the Acteon and Gambier group are allowing wildlife to expand and establish new secure populations, as witnessed for Tutururu and several species of seabird and other animals. For highly mobile species, like seabirds, this expansion is expected to continue and we may see the return of some long lost extirpated species, like the threatened Phoenix and Henderson Petrels. To progress the recovery of Titi and Tutururu, we will translocate them to one of the more distant restored atolls [Temoe, over 300 km away from their current populations], helping secure them a more stable future.”

“Given that five years of recovery is barely a ripple in the prior hundreds of years of harm, it’s deeply satisfying to see such a vibrant transformation.”Tehani Withers, Island Restoration Manager, SOP Manu

Other benefits

But it has not all just been for the birds. Coconut farming, alongside fishing, is the main source of income for these Island communities. In the Tenania atoll, coconut plantations were being damaged by Black Rats, impacting the community’s ability to generate a continuous source of income. Following the successful eradication of the rodents, no one was more grateful than the Mayor of Tureia, who has reported that the harvest has increased by 50% since the operation, helping families with their children’s education and living expenses.

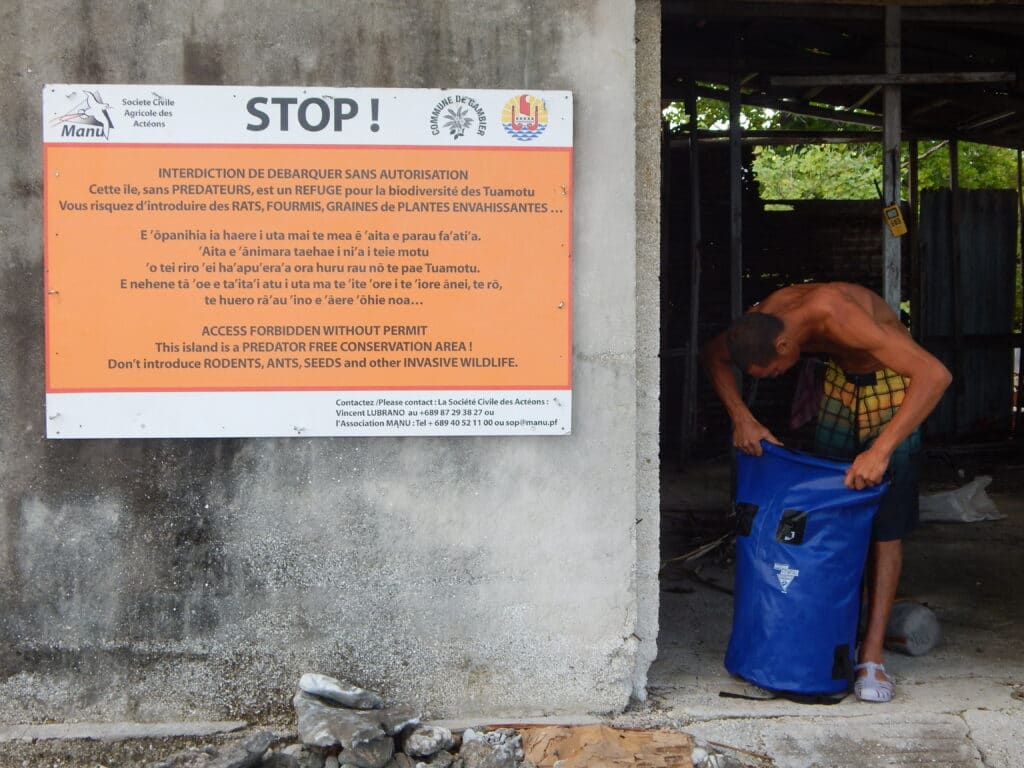

Critical to the ongoing recovery of the islands and their species is biosecurity: to prevent the return of removed species and other harmful introductions. Here, the leadership from local people is crucial. Local communities, the Catholic Church and the French Polynesian government are partners who not only helped make the restoration possible, but also ensure it continues as they remain vigilant in applying biosecurity and educating others in doing the same.

The Polynesian people are deeply connected with nature, playing a crucial role in their traditions, history and way of life (this is also why we use the species’ original names in this article). So when nature is degraded, cultures are too.

Unfortunately, many Pacific islands, including those in French Polynesia, continue to face threats from invasive species and climate change, severely impacting both biodiversity and the Pacific people’s way of life. This form of restoration and capacity building offers a clear solution. It resets the natural balance to a time probably not known on these islands since Polynesian ancestors colonised the thriving ecosystems.

Lessons for future island restorations

So what’s next? SOP Manu is following up with further habitat restoration – clearing more Lantana and removing coconuts that have spread outside plantations. Of course, lessons have been learned from the one island where the eradication of rats failed, Kamaka, and a renewed operation is planned for later this year.

“The use of drone technology is an exciting new innovation to make rodent eradications more accessible on remote islands like Kamaka”, says Tom Ghestemme, Director of SOP Manu. The emotional drive to succeed is now extra strong for this island: “The landowner, the late Johnny Reasin, committed his life to restoring Kamaka and his family are equally committed to continuing the work. SOP Manu will honour his life-long wish and realise his legacy of protecting French Polynesia’s birds and biodiversity.” Situated among three of the other predator-free islands, the potential for seabird recovery on Kamaka is huge.

And it doesn’t end with these islands. BirdLife and BirdLife Partners are currently supporting invasive species operations across at least 16 sites in seven Pacific Island countries, safeguarding 15 threatened bird species and many others, such as the Marquesas and Rapa Iti. “While there is still much to do, the learnings from the Acteon and Gambier operation have been instrumental in making a difference,” says Cranwell. “With your continued support we will turn back the tide of extinction and continue to protect, secure, and restore the unique biodiversity of the Pacific.”

The results of Operation Restoration are a remarkable testament to the rate at which native wildlife can recover given the right opportunity, a heroic effort and with strong local support. While the Tutururu and Titi are not completely safe yet, we can say they have certainly been pulled back from the brink of extinction, and as they continue to increase and expand their ranges across these restored islands, so will the certainty of their future.

This extensive island restoration operation was led by BirdLife International, with SOP Manu (BirdLife Partner in French Polynesia) and Island Conservation.

Since its inception the restoration has been supported by many international and national organisations with significant funding from the European Union, the British Birdwatching Fair, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Government of French Polynesia, The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, the T-Gear Foundation, and National Geographic Society; sponsorships from Bell Laboratories and; assistance from the Gambier Islands Council, Pacific Invasives Initiative, the New Zealand Department of Conservation and many individual people around the world.

“With your continued support we will turn back the tide of extinction and continue to protect, secure, and restore the unique biodiversity of the Pacific.”Steve Cranwell, BirdLife invasive species programme manager

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.