Drones, stretchers and other surprising reasons for Cabo Verde’s turtle nesting boom

Whilst COVID-related restrictions may have benefited turtles elsewhere, the dedication of conservationists is mostly what made 2020 an exceptional Loggerhead Turtle nesting season here

By Shaun Hurrell

For an interview with tips and insight from this conservation project, see Lessons Learned below

With flailing flippers and sandy, narrowing eyes, a large turtle lies exposed on a Cabo Verdean beach in the dark. The Atlantic Ocean spray smells tantalisingly close, but this female Loggerhead is stranded on her back, helpless to her fate. Suddenly: a peculiar whirring sound, then the scuffling of approaching footsteps. Human hands flip her over and she is free to claw her way back to the safety of the sea.

This was the moment a drone saved the life of a turtle. Operated by conservationists Adilson Ramos and Albert Taxonera from Projeto Biodiversidad (a local NGO based on Sal island), their beach monitoring succeeded in scaring away a poacher, who had flipped the turtle – sadly, a common method used locally to tire and render turtles easier to carry and kill for meat later. Spotted through the drone’s thermal imaging camera, the man appears orange-red with anger as he curses at the buzzing drone, before setting the turtle right and scurrying off.

She was just one of many Loggerhead Turtles that managed to nest successfully in the western African archipelago of Cabo Verde this year in what has been a record-breaking season. In the 2000s, less than 10,000 nests were counted per year on Boa Vista, the country’s largest nesting island. Numbers grew in the last decade to over 100,000 for the whole of Cabo Verde in 2018, with the official 2020 count coming in at over 170,000 nests. “Even adjusting for the increase in data over the last few years, this year has been truly exceptional”, says Aurélien Garreau, Programme Officer for Cabo Verde, working as part of the BirdLife Regional Implementation Team for the CEPF*.

Loggerhead Turtles Caretta caretta don’t have it easy. They’re globally Vulnerable to extinction and face threats such as development and disturbance of their nesting beaches, bycatch in fisheries, illegal trade, pollution (including plastic and light), climate change, and poaching for their eggs and meat (in Cabo Verde, where the species is nationally Endangered, this is usually by poachers wanting to sell meat illegally, or consumption as a ‘treat’). Plus, with only one in a thousand turtle hatchlings known to mature to adulthood, increasing nesting success is vitally important to saving the species. But on hot Cabo Verdean beaches, patrolling and scientific monitoring work is not easy. ‘Headstarting’ is also important – involving moving vulnerable nests to simple beach hatcheries protected from dogs, predation and flooding, giving hatchlings the best possible chance of making it to the ocean.

Media attention has recently credited a lack of tourists for increased turtle nesting success elsewhere in the world. Whilst that may be a factor for some Cabo Verdean beaches, many are in more remote areas where COVID restrictions on group numbers and the usual support of international volunteer schemes actually made it harder for NGOs to patrol. Thus, the innovative use of a drone clearly had a positive impact on Projeto Biodiversidad’s work.

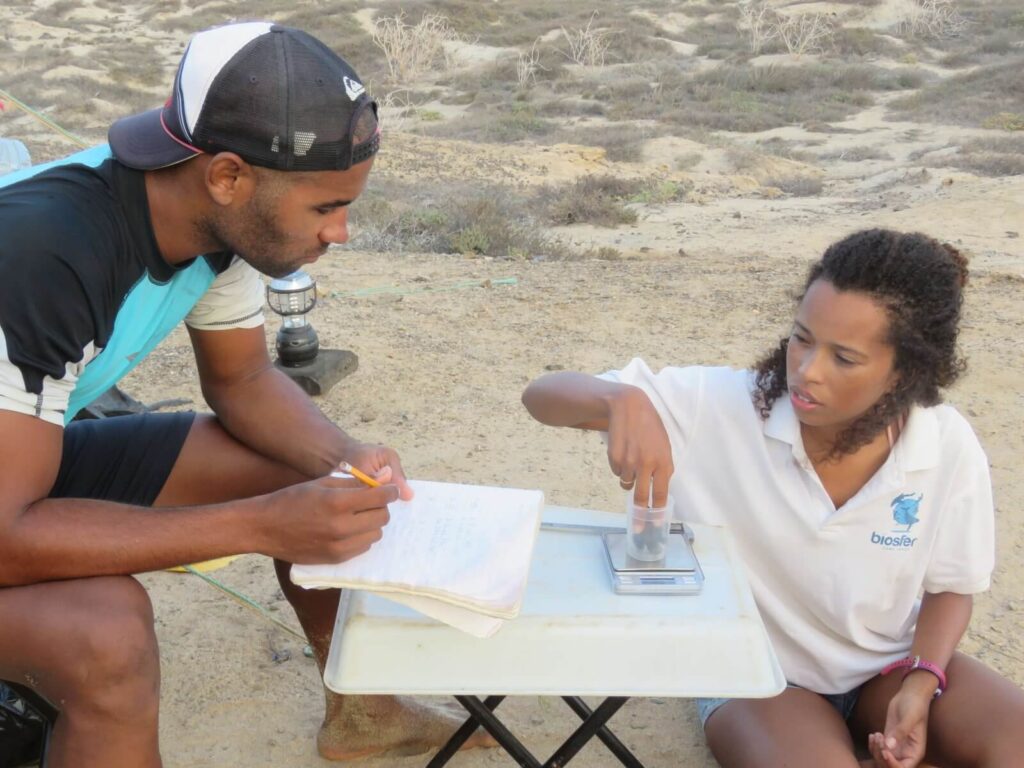

Overall, and despite COVID, it’s the consistency and dedication of the work of many local civil society organisations both on and off the beach that has made the difference for this year’s record nesting success. A total of five such Cabo Verdean NGOs (BiosCV, Biosfera, Fundaçao Tartaruga, Projeto Biodiversidad, and Projecto Vito) have been supported by CEPF, with Biosfera also supported by BirdLife directly through Hatch (for drone training, now underway, and organisational development). Year after year, they have been out on beaches, talking over tea with fishermen, raising awareness in schools and tourist complexes, being interviewed on national TV, and meeting government officials. You may be wondering why the poacher turned the turtle back over; work by these NGOs successfully persuaded the Cabo Verdean government to pass a breakthrough law against turtle poaching in 2018, with prison sentences. This has been fundamental to enforcement, with the police even counting on NGO patrols for convictions.

But don’t let this paint an ‘NGO versus local people’ picture because that’s far from the truth. Local people are much involved with beach patrols in Marine Protected Areas on Sal, Santa Luzia and Boa Vista, and the NGOs develop opportunities for fishing communities such as ecotourism (homestays, guiding) and activities on sustainable fishing. “Thanks to awareness and engagement work, there has been a change in the Cabo Verdean societal vision of turtles”, says Garreau, “to one of pride, and their relation to economic opportunities too”, says Garreau. Loggerheads take over 20 years to reach maturity and return to the same beaches to nest. The immense effort and selfless dedication put in by these NGOs to increase hatching success and community support today will hopefully continue to pay off in years to come.

The reality of a Cabo Verdean beach patrol

Conservationists patrol every day and night during the June to October nesting season

Wake up at 4 AM to begin beach patrols by moonlight (or red torchlight, so turtles aren’t disorientated). Feeling anxious about potential interactions with poachers. Five kilometres of beach and five hours of walking and nest monitoring later, you’re in the scorching sun with no shade and an empty bottle of water. Then you spot a turtle behind the sand dunes 300 m from the ocean, lost and exhausted after nesting and clambering over piles of plastic debris. It takes two of you to use a specially-made ‘turtle stretcher’ to carry the 100 kg dying animal back to the ocean. Is it worth it? Yes. A life is saved, and if the turtles feel safe, they will come back to lay 80-90 eggs 2-3 times in a season.

“A heavy ball that takes a lot of effort to start moving, but once it catches speed, it’s unstoppable!”

The use of drones to patrol against turtle poaching is just one part of Projeto Biodiversidad’s large project that aims to establish cooperative management of a Marine Protected Area on Sal to restore and protect its species. As part of our Lessons Learned series to share advice from civil society organisations, here’s some conservation.Berta Renom, Director of Projeto Biodiversidad

Your project is tackling an important conservation problem. What inspired you to find a solution?

The Marine Protected Area of Costa de Fragata is both a biologically and culturally iconic part of Sal island’s coast. Unfortunately over the last decade we have witnessed the intense and uncontrolled exploitation of its natural resources, threatening the survival of many important species in addition to jeopardising its own Protected Area status. Considering that it is a right of all Cabo Verdean citizens to enjoy a healthy environment, we saw an opportunity to share in this and provide a structured way for them to voluntarily contribute to the restoration of this habitat upon which all we depend.

Tell us one big lesson that you have learned from this project.

One of the most interesting things of this project is that it works, simultaneously, with all three sectors of the society: the public sector, the private, and civil society. We knew that it would be challenging to organise them to work cooperatively towards a common goal. However, we were surprised to realise that both the private sector and civil society were aware of the threats affecting the MPA and willing to contribute to implement the management plan, but reluctant to do it unless they saw evidence of a clear and strong engagement from the public sector. This demonstrates the important role that the authorities play in establishing clear structure and an equality of opportunity when it comes to legislation. Thus, engaging the public sector (e.g. local tourism operators, fishers) as a leader in the process has been key for the success of the project. By developing a respectful economy out of the turtles, we can reduce poaching cases.

Given your experience working on this project, what advice would you have for another conservationist in the Mediterranean who is just starting out?

There are two crucial considerations to bear in mind when implementing a project of this kind and magnitude: the first is that it is necessary to involve all spheres of the society in the project, as they all play a role at some level. The second is that mobilising them always requires much more effort and nuance than that you could ever plan. It is like a heavy ball that takes a lot of effort to start moving and moves slowly at the beginning, but once it catches speed, it’s unstoppable!

Read more in our Lessons Learned series

*The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, and the World Bank. Additional funding has been provided by the MAVA Foundation. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation.

CEPF is more than just a funding provider

A dedicated Regional Implementation Team (RIT) (expert officers on the ground) guide funding to the most important areas and to even the smallest of organisations; building civil society capacities, improving conservation outcomes, strengthening networks and sharing best practices. In the Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot, the RIT is entrusted to BirdLife International and its Partners: LPO (BirdLife France), DOPPS (BirdLife Slovenia) and BPSSS (BirdLife Serbia).

Find out more at www.birdlife.org/cepf-med