How Cabo Verde is becoming a safe haven for seabirds

A new network for seabird research and conservation in Cabo Verde is already making an impact on bird species and the local communities that live alongside them Seabirds are fascinating not only for their beauty

By Elena Serra Sánchez

but also for their biology. They are top predators in the food chain, and many of them spend several years at sea, only venturing into the mainland to breed. As marine predators connected to the whole ecosystem, their eggshells, feathers, and droppings allow scientists to learn about the diversity of our oceans, as well as detecting the presence of chemical pollutants in the sea. Hence, they are trustworthy indicators of marine and coastal ecosystems’ health.

In addition, seabirds are vital to terrestrial ecosystems, especially in remote oceanic islands where nutrient inputs may be scarce. Seabird faeces (known as guano), eggs, and traces of food they drag from the sea, are essential nutrients for the soil, vegetation, and other animals. Those nutrients will eventually be washed into coastal waters by the rain, in turn fertilising the areas where schools of fish develop. Some of those fishes will feed seabirds, thus closing the circle of life. Seabirds, therefore, play a key role in keeping fish stocks healthy. Besides, fishers have historically sought the guidance of these birds to find places with an abundance of fish – the second reason why this group of birds is so important to fishing communities.

Unfortunately, seabirds are among the most devastated and threatened species of wild animals in the world due to the intensifying series of threats they face, both at sea and on land.

Located about 600 kilometres off the Senegalese coast in the central Atlantic Ocean, thousands of seabirds find in the volcanic archipelago of Cabo Verde the mosaic of habitats they need to rest, feed, meet their partners and nest. Although the number of seabirds has significantly reduced over the years, the archipelago is still considered a seabird hotspot, with eight species breeding there.

Cabo Verde is of further importance as it is located on the migratory route of several species, such as the Red-footed Booby Sula sula − which remains for long periods on the islands, possibly to moult. The country is also home to three species and two subspecies of endemic seabirds, meaning that they do not breed anywhere else in the world, such as the Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii and Cape Verde Petrel Pterodroma feae (both Near Threatened), and the Cape Verde Storm-petrel Hydrobates jabejabe.

Despite their value, seabirds are not an obvious part of Cabo Verde’s national fauna due to their secretive breeding behaviour, with many nesting in inaccessible steep cliffs and deserted islands, and venturing on long forays out at sea. Consequently, limited attention had been paid to their study and management in the country.

Shedding light on seabirds and their threats

Building on recent initiatives such as the baseline data on seabirds and their threats drawn by the Seabird Ecology lab of the University of Barcelona since 2009, in 2017 BirdLife International began the largest seabird conservation initiative ever undertaken in Cabo Verde. The initiative, funded by the MAVA Foundation, combined the efforts of thirteen local and international organisations coordinated by BirdLife International, to improve knowledge on populations and threats, and create sustainable management to enable the long-term seabird conservation in the archipelago.

To date, this project has enabled collaboration between different stakeholders from civil society, academia, and government, building a national network between NGOs that used to solely focus on conservation action on their own island. On top of all this, it has also achieved great successes in terms of research, threat mitigation, and awareness-raising. “It was a milestone putting together for the first time all the relevant stakeholders in a partnership for seabird conservation across the country,” said Ana Veiga, coordinator of the Cabo Verde seabirds project at BirdLife.

Nationwide surveys found over 30 new seabird colonies of seven different species and many new nests of endemic or threatened species. In addition, some of the largest colonies in the country were discovered for some species, for example the Red-billed Tropicbirds on Sal Island found by the Associação Projeto Biodiversidade (APB) in partnership with the University of Barcelona (UB). According to Albert Taxonera, APB Co-Director, the story of the discovery is “very special” for this Cape Verdean organisation, which used to see tropicbirds in their morning census at Serra Negra turtle nesting beach. “We had no idea how big the colony was and it was only after talking with the UB that we started counting nests. So far, we recorded over 1,200 tropicbirds − adults and chicks − in different colonies: an off-shore islet, a steep cliff and an inland soft slope”, explains Taxonera.

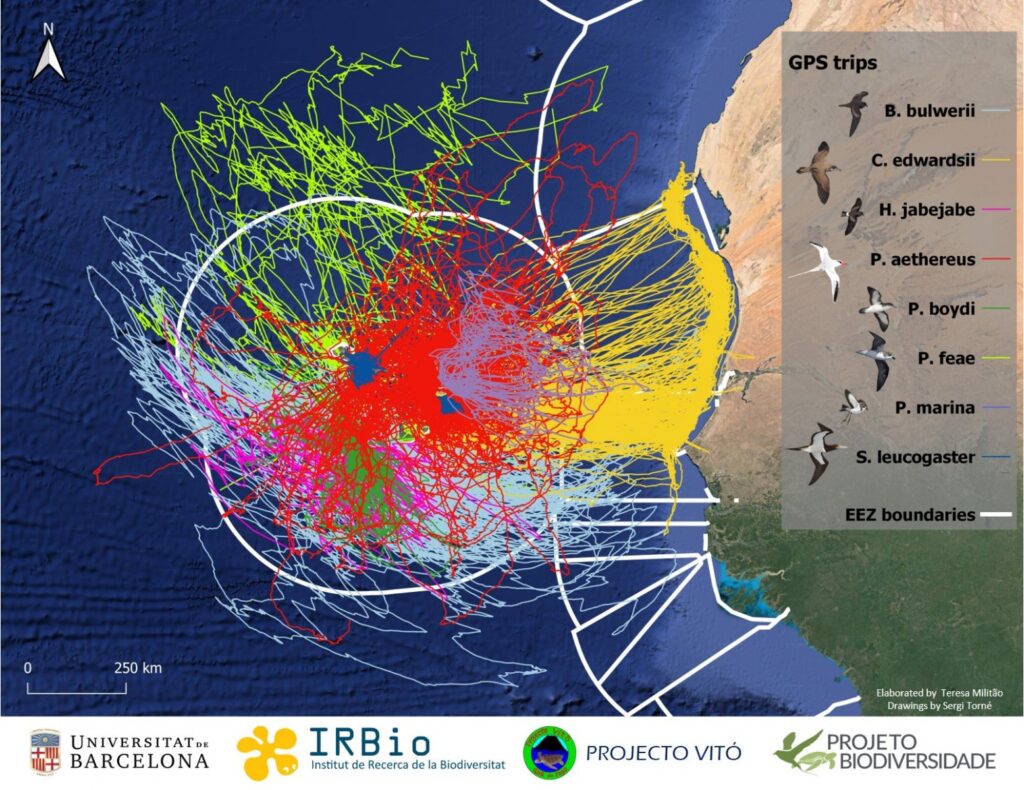

Nearly 7,000 individuals from all breeding species were ringed, and using state-of-the-art tracking technology (comprising 2,016 GPS and 418 Geolocator devices), it was possible to discover the movements of all seabird species breeding in Cabo Verde throughout the year. “This means that, for the first time, we know where these birds are going to find their food and thus, plot where birds interact with fishing vessels”, explains Herculano de Andrade Dinis, the Executive Director of Projecto Vitó, a local NGOs who has been key in the research. “Globally it is estimated that 700,000 seabirds are killed each year by accidentally getting caught in fishing gear, so building this kind of knowledge is a first step to mitigate the negative impact of fishing activities”, adds Ahmed Diame, Bycatch Project Manager at BirdLife Africa.

Unfortunately, the dangers to seabirds are not limited to bycatch. A key aspect of this project is to identify threats and mortality factors affecting seabirds in Cabo Verde. “We identified that invasive alien species and illegal, regular and widespread landing landing on protected islets where the main seabird colonies are located, are the main threats. The disturbance caused has already a severe impact on the seabird breeding success and it is know that alien invasive predators − specifically fire ants, rats, mice and even feral cats or dogs − can even cause local extinctions. Moreover, biodiversity loss also occurs through light and noise pollution, littering, and even direct poaching of eggs, adults and chicks,” explains Pedro Geraldes, Senior Conservation Officer at SPEA.

Fostering stewardship among Cabo Verdeans over their rich natural heritage

The research laid the foundations for addressing these threats, and mitigation action has begun in many cases, for example, controlling populations of invasive alien species. In fact, first successes can already be celebrated: no killing of seabirds has been recorded on key islets such as Raso, Branco, and Rombo over the last two and a half years.

However, conservation efforts to effectively protect breeding zones were hampered by reduced community engagement. To address this challenge, the partnership undertook extensive work to raise awareness among schoolchildren, local communities, and the wider public, and to promote sustainable practices among fishing communities. Some tangible results include the new seabird interpretation centre: the centrepiece of a far-reaching communication campaign which included a seabird exhibition attracting 5,000 visitors, over 100 radio shows, a website dedicated to the Cabo Verde seabirds, and the ECOSTAR television series.

For the ECOSTAR documentaries, six Cape Verdean personalities lent their image to the seabirds’ cause accompanying the local NGO Biosfera in monitoring and observation activities in Raso and Fogo islets. “Cape Verde Television (TCV) broadcast the six episodes of the ECOSTAR in prime time, which was a great opportunity to make the general public aware of the beauty of seabirds and their threats,” explains Blandine Mélis, director of Biosfera.

Reduced staff and enforcement capacity also hindered the protection of critical sites. To tackle this issue, the Direção Nacional do Ambiente (the National government environmental agency and one of the project partners) stepped in to continuously train judges, bailiffs and enforcement agents on seabird conservation and Protected Areas legislation. Furthermore, a new policy to address the impact of invasive alien species was drafted throughout the project and is now under Federal Government review.

Even though the project has achieved great successes in Cabo Verde, there is still a lot of work to be done. “Our future priorities will focus on conservation actions such as the management of invasive alien species, mitigating seabird bycatch, better management of Marine Protected Areas, addressing impacts from the energy industry, strengthening the national seabird conservation network, and fostering new environmental policies collaboratively developed by local partners,” explains Alfonso Hernández Ríos, Marine Programme Coordinator at BirdLife Africa.

BirdLife International also seeks to engage directly with communities living around protected areas. “We believe that empowering local communities in conservation action and [helping them to] become stewards of their natural heritage is part of what drives long-term behavioural change,” states Thandiwe Chikomo, Head of Capacity Development at BirdLife Africa.

Indeed, local NGOs like Projecto Vitó and Biosfera have already benefited from the project, increasing their technical skills, conservation actions, and engagement with fishing communities. In the same way, young Cape Verdean scientists, field technicians, and conservationists are now trained to study, manage and care for Cabo Verde’s rich seabird heritage into the future.

The Cape Verde seabird project financed by the Mava Foundation and coordinated by BirdLife International has brought together a partnership of thirteen local and international organisations for the long-term conservation of seabirds. Five funded partners: Direção Nacional do Ambiente (DNA), Associação Projecto Vitó (Vitó), Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves (SPEA), University of Barcelona (UB) and Biosfera 1 (Biosfera). Other indirect partners that collaborate with the project: Instituto Nacional de Investigação e Desenvolvimento (INIDA), Universidade de Cabo Verde (Uni-CV), & University of Coimbra (UC), BIOS.CV (Bios), Associação Lantuna (Lantuna), Fundação Maio Biodiversidade (FMB), Associação Projeto Biodiversidade (APB) &, Associação Amigos do Calhau (AC).