How are seabirds doing in the EU and UK?

Despite the hellish outcome from the Ancient Mariner’s slaying of the albatross in Coleridge’s epic poem, the delirium the sailor suffers conveys a vibrant vision of healthy bird populations tragically absent in our latest research on seabirds.

By Antonio Vulcano, Claire Rutherford, Anna Staneva & Daniel Mitchell

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

Globally, seabirds have declined by 70% in the last 50 years and are currently the most threatened group of birds in the world according to a study led by the University of Aberdeen (2018).

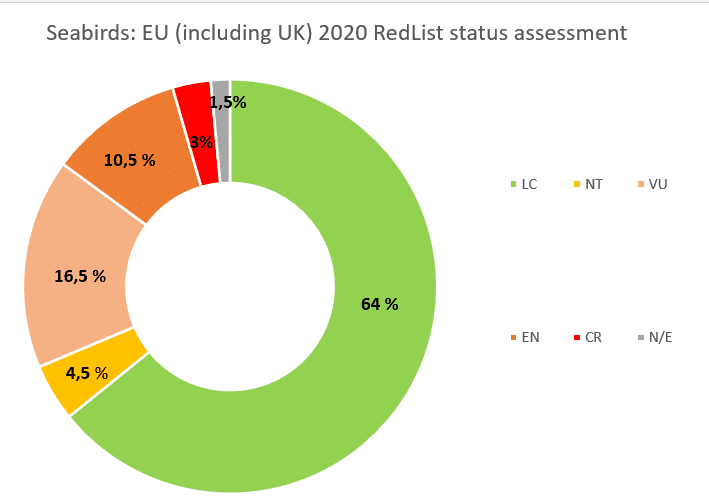

Our own seminal work in 2020 assessing and updating the EU Red List bird population status and trends of 463 bird species breeding and/or wintering in all EU countries and the UK, between 2013-2018, showed similarly distressing results. For seabirds, overall, the picture looks grim.

Led by Birdlife International, the latest worldwide review of threats to seabirds in 2019 found that the main global perils to seabirds are Invasive Alien Species (mainly introduced mammals, reptiles, plants or bird species), bycatch in fishing gear, and climate change, & severe weather About 70% of seabirds, especially globally threatened species, face multiple threats.

Across the EU, we see that the top current threats for seabirds identified by Member states (under article 12 of the birds Directive) are in line with global patterns: Invasive Alien Species, bycatch and recreational activities (sport, tourism and leisure) during the breeding season, whereas wintering birds are most threatened by bycatch, prey depletion, and wind, wave & tidal power. This combination of on-land and at-sea hazards can make seabirds particularly sensitive to rapid declines in the region, even species with stable or increasing trends and common ones.

But is it all doom and gloom for our old-world voyagers? Let’s look closer.

Still endangered: The case of the Black-legged Kittiwake

This small, northern gull is listed as Endangered, with its population declining over its entire breeding range, and is, in some places, nosediving. It is one of 13 species which remain threatened with no change to their Red List status since the last EU assessment in 2015.

Human driven activities are impacting Kittiwakes breeding: parents are unable to find sufficient fish to feed their chicks as overfishing and climate change drive their main prey (sandeels and capelins) further North from their nesting cliffs. These birds are stuck between a rock and a hard place. In a bid to survive, they can either switch to different prey or try to follow their preferred food further North. Both options will negatively impact their breeding success as parents must exert more effort for the same level of nutrition, until they cannot sustain their chicks’ needs anymore, which will ultimately starve to death. In order to protect these seabirds, it is crucial that we do more monitoring of the other threats these seabirds face in their wintering grounds, such as overfishing, marine pollution and bycatch to guarantee Kittiwakes have good quality wintering areas. This is essential to allow them to breed successfully and stop them from heading towards extinction.

In decline: The case of the Northern Fulmar

The once common Northern Fulmar is one of seven species which has been moved to a higher threatened category in Europe in our latest assessment.

Their populations expanded through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thanks to discards from fisheries and natural changes in food availability, coinciding with a period of warming in the temperate North-Atlantic waters. But Fulmar populations are now declining, even in places where they were once abundant. Bycatch in some areas could be driving the unsustainable trends seen in local populations, with a deadly impact on adult survival.

Improved statuses: The case of the European Shag

It’s not all doom and gloom though, as eight species have had their threat status downlisted, including the European Shag. The European Shag, which was classed as Threatened in 2015, is now re-classified as Least Concern.

With their characteristic silhouette perching on shoreside rocks and wooden poles to dry their wings after fishing, the coastal and webbed feet European Shag is a bird many people are familiar with. Although Europe is one of this species’ geographical stronghold, Shag chicks suffer from a very low survival rate. The adult population is also threatened by pollution and human activity changing their environment. On top of falling victim to climate change and extreme weather conditions, Shags are also shot and poisoned by fishers and fish-farmers, who see them as competitors for resources. So, although it may seem that the fate of the European Shag is safe for now, as with all seabirds, it is always hanging by a thread. By monitoring this and other ‘least concern’-classified species, we can help prevent future declines.

Keep common species common

The Common Gull is a Least Concern species who despite its status, shows both short and long-term decreasing trends and a declining EU population status. This is in line with the warnings of scientists who have said that many seabird species may diminish rapidly in the next decades and some of them are already following this decreasing pattern. If we do not tackle the threats these birds are facing, including climate change, bycatch, and overfishing, the survival of these Least Concern birds will once again become highly concerning.

Conservation works

Thanks to concrete conservation actions, seabirds on the brink of extinction have recently recovered. Today, we know that targeted conservation actions, such as the eradication of invasive plants and mammals, and the construction of artificial nests, contributed to the improvement of the short-term population trends of the two still threatened petrel species of the Pterodroma family in the Portuguese island of Madeira. The eradication of rats from some Italian islets in Sardinia, Latium and Tuscany also contributed to the recovery of local populations of the Yelkouan Shearwater (Vulnerable).

Seabirds are the link between land, sea and sky. Like all birds, they know no borders. That is why it is crucial for different countries, communities and stakeholders to share responsibility to protect seabirds. By combining the technical knowledge, political will and financial sustainability, seabirds can get the transformative change they need in order to survive, and flourish once again.

Image credits: European Shag © lisalouise

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |