5 ways we’ve helped vultures in the past 5 years

When our first campaign to save African vultures started in 2015, global awareness and political recognition of these majestic raptors were in their infancy. Discover just a few examples of the fantastic achievements that BirdLife supporters helped to kick-start, and find out how you can help us step up our action to the next level.

By Jessica Law

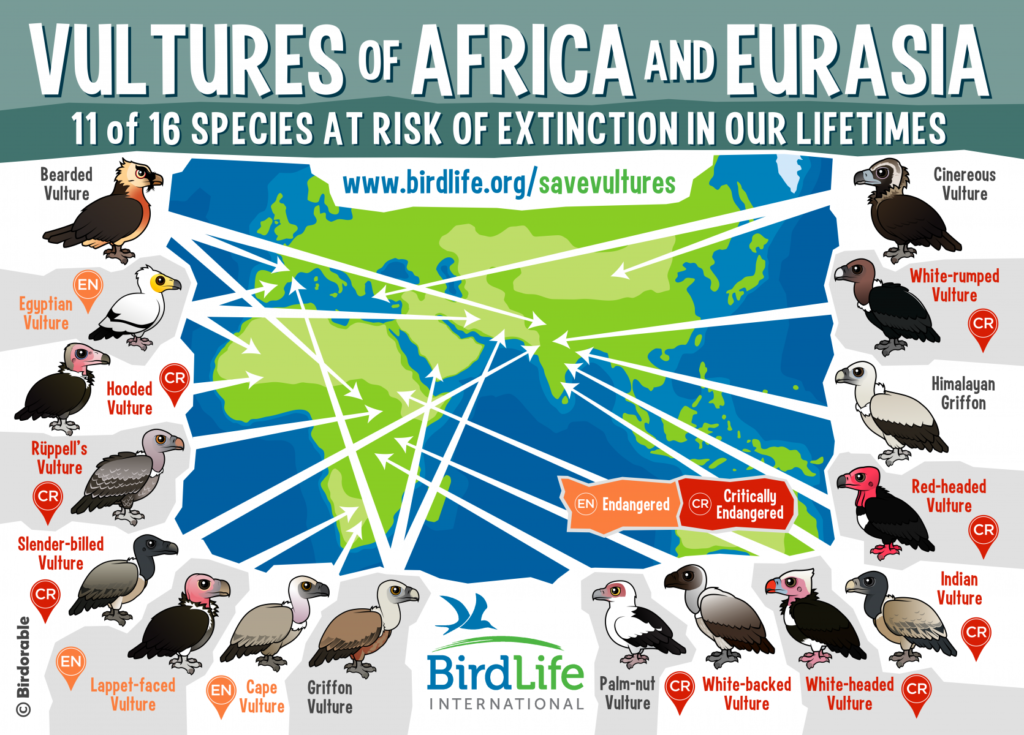

Five years have passed since BirdLife International made an announcement that sent shockwaves through the conservation community: Africa’s vultures are on a steep slide towards extinction. In all, six of Africa’s 11 vulture species were placed in a higher extinction risk category – reflecting sharp populations declines that brought to mind the catastrophic collapse of Asia’s vultures in the 1990s.

Although the reasons behind the population collapses were different from continent to continent, the end result, if action was not taken, would be the same; the disappearance of one of the world’s most charismatic and recognisable bird groups from our skies, and the loss of the valuable ecological benefits these efficient scavengers provide.

While the situation is still stark, important gains have been made, both on the ground and in terms of raising awareness of the plight of vultures. When our first campaign to save African vultures started in 2015, global awareness and political recognition of these majestic raptors were in their infancy. Discover just a few examples of the fantastic achievements that BirdLife supporters helped to kick-start, and find out how, with your help, we can step up our action to the next level.

1. Vulture-safe Zones established in Nepal and beyond

Everyone needs a safe space, and vultures are no exception. One of the biggest causes of Asia’s catastrophic vulture decline is veterinary diclofenac – a painkiller often used on livestock, but which is deadly to vultures that scavenge on their carcasses. In the 1990s, 99% of the Indian subcontinent’s vultures were wiped out by the drug. To prevent further tragedy, our Partner Bird Conservation Nepal, working under the Saving Asia’s Vultures from Extinction (SAVE) consortium, set up a network of “Vulture Safe Zones”, using community engagement and advocacy to end the sale of veterinary diclofenac, which had been banned in 2006 but was still stocked by many outlets.

This strategy was accompanied by a community programme called the Jatayu Restaurant, involving the purchase of elderly cattle at the end of their working lives, saving local people from feeding or abandoning an animal that is otherwise a burden – especially since Nepal’s large Hindu population respects cattle and have strong cultural appreciation for cows. The cattle are allowed to live out their natural lives in comfort, and afterwards provide much-needed nontoxic food for vultures. As many as 150 vultures at a time have been spotted feasting at Nepal’s “vulture restaurants”.

The results soon became apparent. A study released this year found that Slender-billed Vulture Gyps tenuirostris numbers had started to increase in 2012, with White-rumped Vultures Gyps bengalensis following suit in 2013. Undercover investigations in pharmacies reported that sales of diclofenac had also been successfully phased out around this time. Then, in a landmark moment for conservation history in 2017, six captive-reared White-rumped Vultures were released into a wild that, for the first time in decades, could be truly vulture-safe. Today, the number has risen to thirty vultures, which have since travelled far and wide.

Vultures are long-distance foragers that don’t just stay in one country, and the Vulture Safe Zone model has been rolled out across Asia. This month, BNHS (BirdLife in India) released eight captive-reared White-rumped Vultures in Haryana, India. Like their Nepalese counterparts, they were fitted with satellite tags to monitor their movements, health and survival. The concept is also being adapted for Africa, where the first Vulture Safe Zones have already been declared. BirdWatch Zambia (BirdLife Partner) has been leading the charge with a growing number across the country and more in the pipeline. The model has also spread to Zimbabwe, South Africa and more. Participating landowners have agreed to stop baiting carcasses with poison and to address belief-based use, with a focus on awareness-raising and positive messaging.

2. Rapid-response vulture rescue protocols in Kenya

The problems African vultures face are more diverse. In Kenya, where human populations often come into contact with wild animals, farmers may put out poisoned bait to kill predators such as lions that may have taken their livestock. The vultures that scavenge on these carcasses are poisoned in turn. But if people act fast, hundreds of vultures can be saved.

In 2016, Nature Kenya (BirdLife Partner), working with the Kenya Wildlife Service and The Peregrine Fund, introduced a rapid response protocol whereby a poisoned carcass could be spotted and disposed of before it could cause any more deaths. They trained 89 rangers across the Masai Mara to deal with the source of poisoning, get veterinary help for sick animals, and even gather evidence to find and prosecute perpetrators. The rangers went on to train 117 more colleagues, sharing their knowledge far and wide.

To spread the word further, Nature Kenya embarked on a large-scale publicity campaign. In villages across the Mara, rangers attended regular barazas (village meetings) to talk to local people. Performance groups such as the Buffalo Dancers raised awareness at markets, and a “Vanishing Vultures” documentary was aired on national television. At every opportunity, residents were told who to contact and what to do if they witnessed a poisoning.

Almost instantly, the campaign began to prove invaluable: researchers, rangers and local community members called the rapid response unit into action on numerous occasions, saving hundreds of vultures every time. Furthermore, poisoning itself became less common. From 2017-2019, the planned poisoning of two lion prides was averted, and the overall poisoning of vultures in the Masai Mara dropped by more than 50%.

3. Landmark policy resolution on vulture-toxic drugs

For several years, BirdLife has been pushing for a strong intergovernmental policy on the veterinary use of diclofenac and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that could also be deadly to vultures. Finally, in February this year, a resolution adopted by the UN Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS) covered their use and regulation as never before, offering new hope.

The resolution, which was adopted at the thirteenth CMS Conference of Parties, outlined four key actions that perfectly reflect what we have been calling for: tests on all existing veterinary NSAIDs to determine which are harmful to vultures and which are safe; withdrawing licencing from those that are vulture-toxic; safety-testing new veterinary NSAIDs before they are licenced; and identifying and promoting safe alternative drugs.

According to Roger Safford, Senior Programme Manager in BirdLife’s Preventing Extinctions Programme, the safety-testing of both new and existing NSAIDs is particularly vital: “We need to look at all the veterinary anti-inflammatories and withdraw from veterinary use the ones that are toxic to vultures. If we replace diclofenac with another drug that is just as toxic to vultures, then we just perpetuate the problem.”

Once we know which drugs are harmful, governments of vulture range states can ban their use on livestock and suggest safe alternatives. Our next step is to ensure that governments follow up on this commitment, against the powerful pharmaceutical lobby. This could be difficult – despite knowing the risks, several European countries approved diclofenac for use on livestock in 2014. Such a precedent increases the chances of similar licensing in Africa. However, we know we are up to the task. In 2017, in the face of intense lobbying from pharmaceutical companies, BNHS and SAVE persuaded the Indian government to uphold the ban on large vials of diclofenac which were being misused for veterinary purposes.

4. Vastly improved public and political awareness

Be honest – what used to be your first impressions of vultures? Sinister harbingers of death? Tough, common scavengers that can look after themselves? Over the past five years, vultures have undergone a huge image transformation in a wide range of sectors. In science, new research resulted in 15 vultures being classed as globally threatened on the IUCN Red List. Most of them have also been added to Appendix I of the CMS, placing additional obligations on Governments to protect them. Numerous studies have advanced our understanding of these fascinating creatures and how best to help them.

On a political level, speaking out for vultures at high-profile meetings has led to some promising breakthroughs. In 2017, the CMS Parties adopted a Multi-species Action Plan for African-Eurasian Vultures which BirdLife helped to develop. This action plan provides a roadmap for businesses, landowners, NGOs and governments in all 128 African and Eurasian vulture range states, outlining the steps needed to protect all 15 threatened species.

In 2019, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) added West African vultures to their highest-priority list due to the trade in vulture parts. They mandated the formation of a working group to research this pressing concern and put forward policies to combat it. Many of these policies are based on the aforementioned Multi-species Action Plan.

But sometimes, awareness-raising can boil down to something as simple as social media. Our global #LoveVultures campaign showcased the intelligence and beauty of these raptors, as well as the vital clean-up services they perform for us. Every positive image we put out there helps increase the public’s sympathy and concern for these creatures.

5. The next step: tackling illegal trade

It was only when we expanded our work into West Africa that we became aware of the true impact of illegal trade on vulture populations. Here, vulture body parts are often sold for ‘belief-based use’, in sadly misinformed attempts to treat a range of physical and mental diseases, or to bring good fortune. In fact, 29% of vulture deaths in Africa were estimated to be due to this practice. This will be our next challenge, and it’s one the BirdLife Partnership is already making in-roads into.

In May 2019, our Partner, the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF), kicked things off by launching a new countywide project to end vulture poaching. Birdlife in Africa announced ambitious plans to reduce illegal wildlife trade in Nigeria by 20% by 2021. This is a particularly urgent concern, since the illegal wildlife trade has become the second highest criminal revenue generator in the country, after the illicit drug trade. As well as decimating Nigeria’s own vulture populations, the demand in Nigeria is placing pressure on the vultures of neighbouring countries. What’s more, citizens risk ingesting remnants of poisoned vultures.

Encouragingly, attendance at the launch conference was extremely broad, including belief-based practitioners, academics, law enforcement, hunting associations and the media – evidence that there is a strong constituency within Nigeria dedicated to protecting vultures.

Next, NCF began working with traditional healers directly, holding workshops to raise awareness of the vultures’ plight and promote plant-based alternatives to vulture parts. So far, more than 80 traditional healers have taken part in these workshops. The goal is to create a manual on wildlife-friendly medicine practices published in local languages. According to NCF, attendees are now openly using plant-based alternatives, and are encouraging more healers to do the same. NCF has formed a social media group to promote and share experiences of vulture-safe options.

BirdLife’s work on vulture poisoning in collaboration with other organisations was made possible through its membership of the Restore Species partnership, which works to prevent extinctions caused by illegal and unsustainable trade and hunting, and poisoning.

Much of the work reported here, particularly but not only in Asia through the SAVE consortium, has been supported both technically and financially by the RSPB, BirdLife in the UK.

BirdLife International would like to thank everyone who has supported our vulture work over the years, including:

Pamela and Neville Isdell and Cara Isdell-Lee, The Isdell Family Foundation, A. G. Leventis Foundation, Tasso Leventis Foundation, BirdLife Rare Bird Club, BirdLife Species Champions for African vultures: Sean Dennis and Barry Sullivan, BAND Foundation, Fondation Segré, US Fish and Wildlife Service, EU LIFE+, Supporters of the BirdLife Gala Dinners – Japan, Champions of the Flyway and, of course, the many supporters who have responded to our appeals.