Putting people and rights at the heart of conservation

Healthy economies and societies need a healthy environment, so conserving nature is good for people – but for it to be both equitable and effective, conservation has to be done with and for local people. Key to this is recognising and implementing the universal right to a healthy environment, including the rights and role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and embedding these provisions in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

Calling for an equitable, carbon-neutral, nature-positive future

There is increasing recognition from the conservation community of the importance of rights, equity and justice within conservation and, specifically, the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. The concept of equitability came out very clearly from a series of multi-stakeholder Virtual Biodiversity Dialogues we held back in June/July, sessions of the Nature for Life hub we co-hosted on the edges of the UN General Assembly in September, and our joint call to action to world leaders meeting at the UN Summit on Biodiversity – which stated that, “Actions for nature cannot be met without addressing both the climate emergency and social inequalities,” and called for an equitable, carbon-neutral, nature-positive world.

Head of Policy, BirdLife International

Recognising the universal right to a healthy environment

One of BirdLife’s top priorities and a really key opportunity right now is working to ensure a healthy environment for healthy societies, through the universal right to a healthy environment and integration of this right across the UN and multilateral environmental agreements, including the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. This is the aim of the BirdLife Partnership’s 1Planet1Right campaign.

As part of the campaign, BirdLife joined forces with 975 civil society organisations, Indigenous Peoples, social movements and local communities in a global call for the UN Human Rights Council to recognise the human right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. There is considerable and growing support for this, backed by a wealth of evidence and consultations from the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, and in September, during the Council’s 45th meeting, Costa Rica led a joint call with the Maldives, Morocco, Slovenia and Switzerland for this right to be recognised.

This is just the first step. Next we need this right to be recognised by the UN General Assembly, and to be better integrated across the UN and into wider environmental treaties and national implementation, such as through the UN climate convention’s Paris Agreement and, critically, in the targets, indicators and enabling conditions of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework currently under negotiation. This should include formal recognition of the customary rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs), protections for environmental and human rights defenders, and the enshrinement of fair and equitable access and benefit sharing.

Our local-to-global approach to conservation and human rights

As one of the founder members of the Conservation Initiative on Human Rights, established in 2009 by seven international NGOs, BirdLife has long been working around the world to support these rights on the ground as well as at policy level. Examples of BirdLife Partners’ work around the world include:

- supporting indigenous women forest defenders in the Philippines to engage in forest governance processes,

- developing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the Canadian boreal forests,

- reviving the traditional ‘Hima’ conservation areas approach in Lebanon,

- supporting community associations to manage forests in Madagascar, and

- restoration of the Iraqi marshes for the indigenous Marsh Arab tribes.

Addressing the challenges

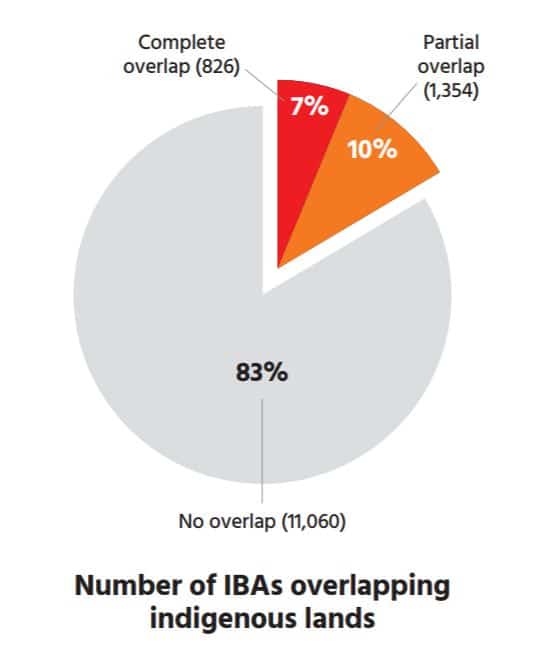

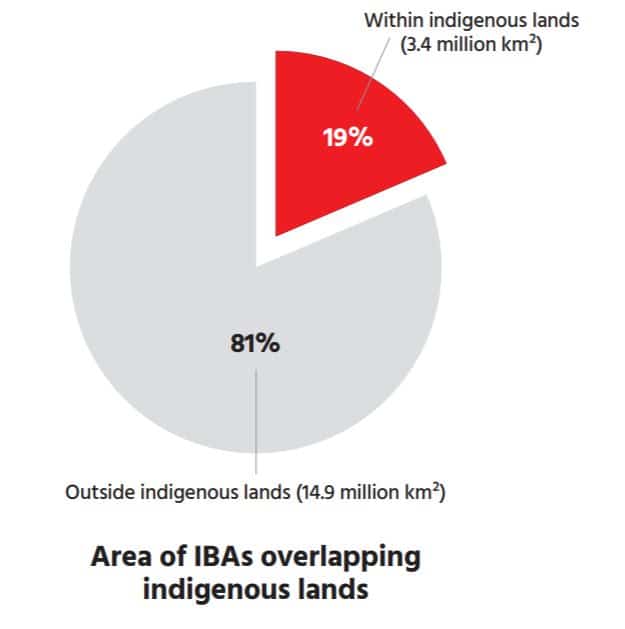

As shown in our recent Birds and Biodiversity Targets report, one-fifth of the entire area of the Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) network (which comprises the majority of Key Biodiversity Areas identified to date) falls within lands managed by Indigenous Peoples or for which they have tenure rights. This means there are considerable opportunities for traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of IPLCs to be integrated into the conservation of these sites. We are therefore working to ensure that the role and rights of indigenous peoples and local communities as stewards and defenders of nature is recognised, protected and supported. This is important both to ensure conservation outcomes – which should also benefit IPLCs, who rely on a healthy natural environment – and to safeguard IPLCs from any potential adverse impacts of conservation policies.

This is not always straightforward, however. In some places there is a lack of national provisions to support IPLC rights, and/or government policy has tended towards fortress-style conservation that excludes IPLCs. Such policies can be both ineffective and inequitable (and in some cases have resulted in major human rights abuses), so, following the logic above and as studies have shown, are bad for conservation as well as people. This is why we’re working at three levels: (1) globally, to ensure much stronger universal recognition of IPLC rights, (2) nationally, to build our Partners’ capacity generally to understand and influence national policies and legal frameworks, and (3) locally, helping Partners then support other stakeholders such as IPLCs to engage in these (such as in our Asia-Pacific Forest Governance project) – to stand up for both their rights and the rights of nature on the ground, which ultimately are one and the same. (See here for more on our capacity building work via Hatch.)

Working with local people to protect and conserve more nature, better

To address rights-based concerns regarding the push for ’30 by 30’ through the post-2020 global biodiversity framework – the conservation of 30% of the land and sea that is most important for biodiversity by 2030 (up from the current target of 17% of land and 10% of sea by 2020) – we need to be quite clear about how we should achieve this target. As recognised in the current draft of the proposed target in the framework, for such an expansion to be effective and feasible in terms of cost, space and equitability, the focus must encompass not only government-protected areas, which in some cases may exclude people, but also indigenous and community protected areas and ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs), often implemented by and for people. Local people must have a stake in ensuring conservation outcomes, and be supported to manage and monitor these areas accordingly.

In our Birds and Biodiversity Targets report we also outline some recent BirdLife research showing that potential OECMs such as community reserves and other community-based approaches appear to cover a high proportion of Key Biodiversity Areas outside protected areas, and so there seems huge potential to recognise the role of OECMs in achieving any post-2020 expanded site-based conservation target.

While the right to a healthy environment can seem a rather obtuse legal concept, you can read more about how BirdLife and Partners are standing up for this right all over the world, for example as we challenge Portugal’s proposed Tagus estuary airport expansion, call for government responsibility for preventing wildfires such as those in the Brazilian Pantanal, and support indigenous women forest defenders in the Philippines.