10 amazing birds that have gone extinct

How do we conserve birds? By learning from previous threats. Hundreds of species of bird have been wiped out by human activity in the modern era. Here are just a few species that illustrate the major threats still facing birds today.

Mysterious Starling – Aplonis mavornata

First described from a single specimen that was shot “hopping about on a tree” in 1825. Ornithologists did not visit Mauke in the Cook Islands for another 150 years, but when they did, they found that the bird had “mysteriously” disappeared. Even more “mysteriously”, introduced brown rats appeared to have taken their place. Can you solve the riddle of the Mysterious Starling?

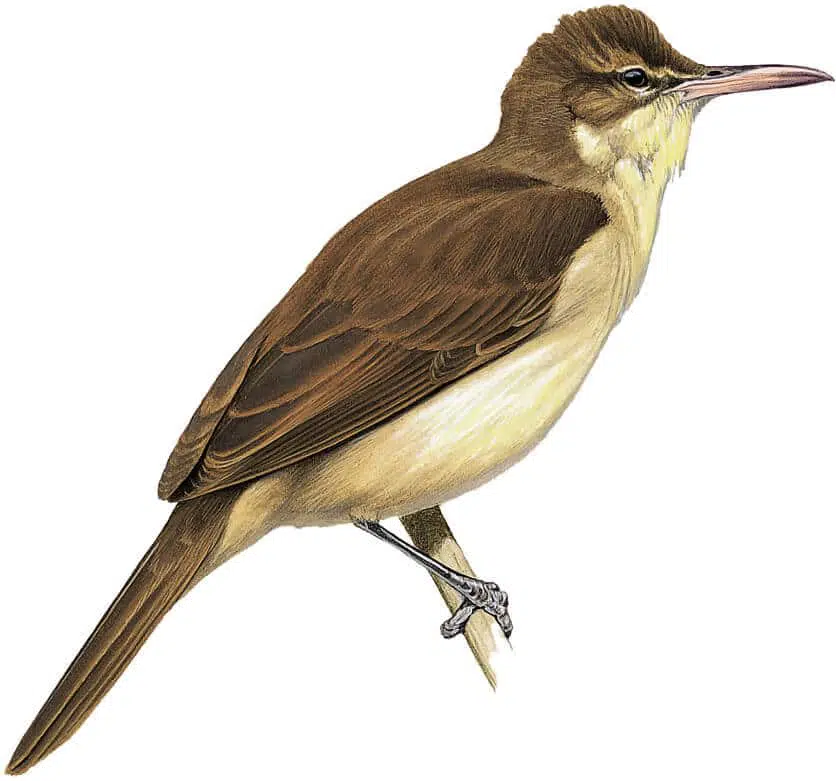

Pagan Reed-warbler – Acrocephalus yamashinae

Many Pacific island reed-warblers are highly threatened by invasive species, and some have already gone extinct, such as this rangy looking bird from the Northern Mariana islands. The Pagan Reed-warbler was until recently considered a sub-species of the Guam Reed-warbler Acrocephalus luscinius, an extinct bird from the island of Guam which was wiped out in the 1960s by introduced plants, animals and habitat degradation. A decade later, the Pagan Reed-warbler followed it into the history books.

Least Vermilion Flycatcher – Pyrocephalus dubius

Newly-recognised as a distinct species in 2016, this glossy, scarlet-and-black insectivore has the unwanted distinction of becoming the first avian extinction recorded in the Galapagos. First discovered during Charles Darwin’s voyage in 1835, invasive plants soon began crowding out the islands’ native vegetation, which in turn led to the decline of the bird’s favoured insects. The resultant food shortages, coupled with avian pox and malaria, probably led to the species’ demise as the last reliable sighting was in 1987.

North Island Piopio – Turnagra tanagra

Habitat loss and predation by cats, rats and people caused this oriole’s extinction. Known from New Zealand’s North Island, the last confirmed record dates from 1902, and there were no reports at all since 1970. The Piopio’s last stronghold later gained protected status when it became Whanganui National Park, but this didn’t occur until 1986, long after it became extinct. There was also a South Island Piopio Turnagra capensis, which became extinct by 1963 for much the same reasons.

Lord Howe Gerygone – Gerygone insularis

This pink-eyed forest dweller was a once-abundant species endemic to Lord Howe Island, Australia. That all changed when a shipwreck washed up on the island’s shores, containing stowaway black rats. These rodents hopped off the sinking ship and began sinking their teeth in the Gerygone’s nests. Last heard from in 1928, none were found on a survey eight years later.

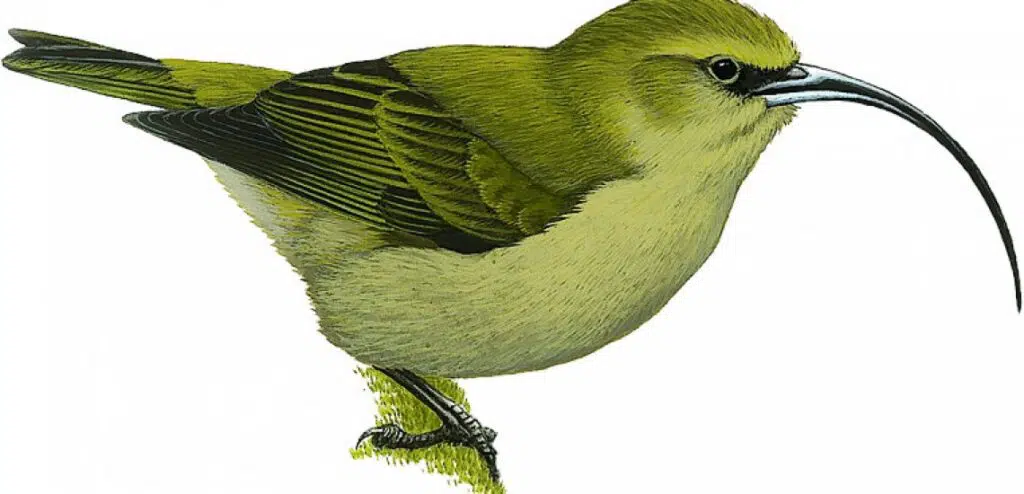

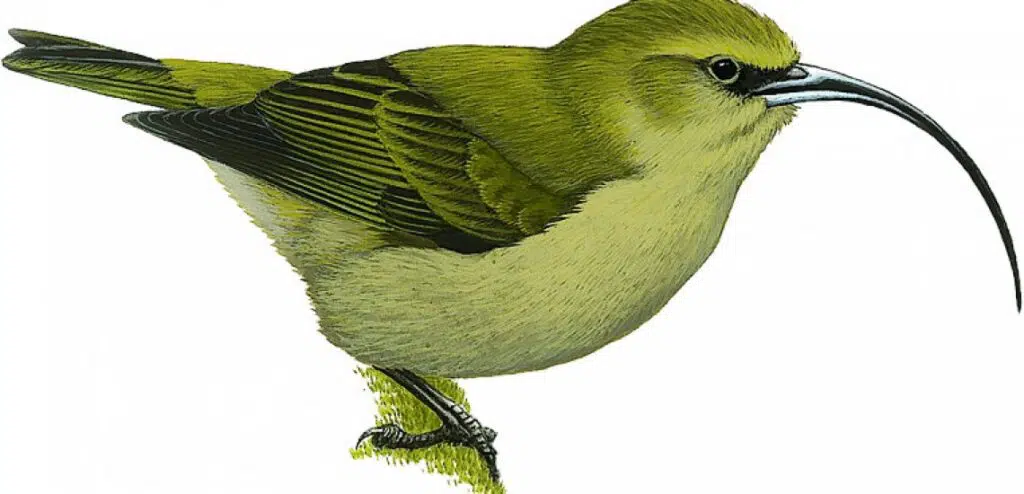

Oahu Akialoa – Akialoa ellisiana

A Hawaiian honeycreeper with a spectacular bill, this insectivore would use its bill to probe through tree bark in search of arthropods, also using it to collect nectar from flowers. Formerly one Extinct species, it is now recognised as one of three separate Extinct species, all of which disappeared as a result of deforestation. It was also presumably susceptible to avian malaria, an introduced disease carried by mosquitoes.

Laysan Honeycreeper – Himatione fraithii

Its close cousin the Apapane Himatione sanguinea is unusual among Hawaiian songbirds because it’s still relatively common. Sadly the Laysan is long gone after introduced domestic rabbits ravaged all the vegetation on the island – including the nectar sources the honeycreeper fed on. In the 1920s, the island of Laysan was battered by a strong storm and the bird was never seen again.

Bishop’s Oo – Moho bishopi

All species belonging to the Hawaiian genus Moho became extinct as a result of man-made threats: deforestation, competition from introduced predators and hunting – their much-sought feathers used to make capes for Hawaiian nobility. The glossy black Bishop’s Oo had a very simple two-note song, took-took, which could be heard from miles away. So, JS Bach this bird certainly wasn’t, but yet it has managed to leave its mark on contemporary music culture. Prolific jazz composer John Zorn released an album called O’o in 2009, named after the late bird, and a mid-nineties indie band from Wales, Mo-Ho-Bish-O-Pi, took their name from the bird’s latin name.

Marianne White-eye – Zosterops semiflavus

So long, Marianne! After agricultural development destroyed its habitat, this white-eye likely became extinct between 1870 and 1890. It was lost long before the successful conservation measures that have rescued many other Seychelles endemics could be implemented. One specimen can still be admired in the Natural History Museum in London.

Bonin Grosbeak – Carpodacus ferreorostris

This extinct finch was described from two sets of skins taken from the Ogasawara islands in Japan during expeditions in the 1820s. Over three decades later, after the islands became a stopover for whalers, naturalist William Stimpson reported that there were no grosbeaks left. Instead, he found countless – you guessed it! – introduced animals, including rats, sheep, dogs, cats, pigs and feral goats.