The wind whispers through the waving reeds while a pair of Marsh harriers (Circus aeruginosus) are flying above the reedbed in Ouse Fen. Small amphibians bubble their way through the waters, and a couple of Great bitterns (Botaurus stellaris) walk secretly through the high grass of the flourishing wetlands.

What sounds like a wildlife fairy tale is an extraction site close to Cambridge. The transformed quarry belongs to Heidelberg Materials who have been collaborating with BirdLife since 2011 to help restore quarries and gravel pits. This long-standing partnership has now been renewed to extend the conservation work, assess impact, and set agendas for large-scale conservation plans globally.

Heidelberg Materials is one of the world’s largest building manufacturers. Their cement, asphalt, and ready-mixed concrete are the pillars of houses, infrastructure, and industrial facilities. But to deliver their product a significant land size is needed to extract gravel and limestone. They own over 600 active quarries across 50 countries, ranging in size from a few hectares up to 1000 hectares. In comparison, the Olympic Stadium in London stands on a 40-ha island. Quarries can be massive but also hold a massive opportunity for wildlife.

The company is aware of its impact and has set the ambitious goal to become net positive by 2030. Over the last decade, BirdLife has supported Heidelberg Materials’ plans to restore nature within its quarries by conducting proximity studies and advising on how to create wildlife-friendly spaces. Both also worked together on ground-breaking sector-relevant policies like the Code of Conduct on species protection.

This public-private partnership resulted in an abundance of quarries that were transformed into large wetlands, fishless ponds for amphibians, and grasslands that are now home to rare orchids. The former sand and gravel quarry Ouse Fen gradually transformed into a 700-ha wetland that will provide the largest reedbed in the UK and is not only home to marsh harriers, bearded tits, and otters but also helped to bring back the extremely rare bitterns to the UK.

But restored quarries across all countries offer a vibrant habitat. The closed ENCI quarry in the Netherlands is turned into shrubs and meadows, allowing for an insect-rich environment in which Red-backed shrikes (Lanius collurio) can thrive. The Górażdże gravel pits and its surrounding riverbeds in Poland will be enriched with islands for nesting and breeding birds.

The renewed partnership sets another milestone in recovering nature and comes with new tangible goals that BirdLife will support. Heidelberg Materials has committed to reserving 15% of their active quarries’ surface for nature by 2030.

“With the signing of this new Memorandum of Understanding, we have the opportunity to strengthen our common long-term objectives. Over this next period, focusing especially on restoration, we will be taking major steps towards becoming Biodiversity Net Positive,” says Dr Nicola Kimm, Chief Sustainability Officer and Member of the Managing Board of Heidelberg Materials.

To establish a nature-positive world, collaborations with progressive businesses are important. While it might sound counterintuitive that these two entities work together to regreen and enrich our world again, this partnership has proven that it is not only possible but that quarries can provide a vital foundation for ecosystems.

Thanks to restored wildlife in quarries, shy bitterns that were on the brink of extinction in the UK, had a chance to bounce back. With the renewal of the partnership, the future will hold even more flourishing wetlands, wet and dry heathlands, and dunes filled with rare species. Former quarries are an important wildlife habitat and shelter for species that otherwise would not survive, they are a pillar in nature restoration and a great example of how coexistence between industry and nature is possible through a joint effort.

Cover picture: ©Yves Adams

© Heidelberg Materials

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

As we celebrate World Wetlands Day, it is crucial to recognize the immense importance of preserving wetlands, which provide a wide array of beneficial services for people and wildlife. Wetlands are highly productive and biologically diverse systems that are vital in enhancing water quality, controlling erosion, maintaining stream flows, and sequestering carbon. They also serve as a critical habitat for fish, waterfowl, and other wildlife, purify polluted waters, and help mitigate the destructive power of floods and storms.

Despite its multiple benefits for the environment and people, wetlands are threatened by various human activities, including urbanism, logging, agriculture, and hydrologic alterations. One of the key aspects of preserving wetlands is their role in maintaining biodiversity and the ecological balance of our planet. Wetlands provide essential breeding, nesting, feeding, and overwintering habitat for a wide range of species, amongst them threatened and endangered species, making their preservation vital for global biodiversity conservation. Furthermore, wetlands are essential for migratory birds, offering crucial resting and feeding grounds during their long journeys.

To address the need to protect wetlands, in 1971, the Convention on Wetlands, called the Ramsar Convention, was adopted, providing the framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources.[1] Ramsar Sites are designated based on the Criteria for identifying Wetlands of International Importance. Though having their criteria, Ramsar Sites have a close and significant connection with Key Biodiversity Areas or KBAs[2].

The crucial connection between KBAs and Ramsar Sites lies in the strong overlap in criteria between the two. Hence, KBAs can offer information about sites that may be suitable for Ramsar designation. In that sense, many KBAs overlap with Ramsar Sites, highlighting wetlands’ critical role in preserving biodiversity. An example of sites designated as Ramsar Sites and KBAs are the Densu Delta Ramsar Site in Ghana, the Lake Junín Site in Peru, and the Jubo Ramsar Site in Pakistan.

Ghana’s Densu Delta Ramsar Site comprises an open lagoon, saltpans, freshwater marsh, scrub, and sand-dunes. It was designated a Ramsar Site in 1992 and qualifies as a Key Biodiversity Area of international significance. The site is threatened by increasing urbanization, with uncontrolled and unauthorized housing development resulting in habitat destruction[3].

Lake Junín, located in the Andean highlands of Peru, is a significant Ramsar Site and Key Biodiversity Area (KBA). This lake is renowned for its abundance and diversity of waterbirds, serving as a critical habitat for various breeding, staging, and wintering species. Notably, it supports the entire global population of three species or subspecies: the Junín Grebe (Podiceps taczanowskii), Junín Rail (Laterallus tuerosi), and the endemic subspecies of the White-tufted Grebe (Rollandia rolland)[4].

The Jubo Ramsar Site in Pakistan is a Key Biodiversity Area of international significance because it meets one or more Alliance for Zero Extinction sites and Key Biodiversity Areas. It is a terrestrial and freshwater system with an altitude ranging from 0 to 0 meters and an area of 5,276 hectares. The site holds species at risk of extinction or ecosystems at risk of collapse[5].

World Wetlands Day serves as a reminder of the invaluable services wetlands provide to both people and wildlife. Preserving these vital ecosystems is essential for maintaining biodiversity, mitigating climate change, and ensuring the well-being of present and future generations. We must continue to raise awareness and take concrete actions to protect and conserve wetlands for the benefit of all life on Earth.

[1] Wildlife Practice. February 2017. Technical Paper: The relationship between Key Biodiversity Areas and other designations. https://kbacanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/WWF2017_Technical-Paper-The-Relationship-Between-KBAs-and-Other-Designations.pdf

[2] KBAs are sites that contribute significantly to the global persistence of biodiversity and are identified under the “A Global Standard for the Identification of Key Biodiversity Areas” approved by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

[3] Key Biodiversity Areas Partnership (2024) Key Biodiversity Areas factsheet: Densu Delta Ramsar Site and vicinity. Extracted from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/site/factsheet/6342

[4] Key Biodiversity Areas Partnership (2024) Key Biodiversity Areas factsheet: Lago de Junín. Extracted from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/site/factsheet/14788

[5] Key Biodiversity Areas Partnership (2024) Key Biodiversity Areas factsheet: Jubo Ramsar Site. Extracted from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. https://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/site/factsheet/16448

By Daniel Mitchell

The announcements by the UK and the Scottish Governments that industrial sandeel fishing will no longer be permitted in English and Scottish waters is a crucial step towards safeguarding seabird populations and rebuilding the resilience of the North Sea ecosystem.

Despite their small size, sandeels are highly nutritious and a much sought-after meal. Iconic seabirds such as the Black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), the Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), and the Common guillemot (Uria aalge), marine mammals such as the Minke whale, the Harbour porpoise, and the Harbour seal, and even certain commercial fish species such as cod and haddock, all rely on this valuable fish.

This measure comes at a critical time. OSPAR’s authoritative Quality Status Report, released towards the end of 2023, highlighted the poor state of seabird populations across the North East Atlantic. [1] Seabirds that feed near the surface are faring worse, with climate change and fishing primarily responsible for reducing the availability of food.

Vessels fishing for sandeel in the North Sea target the same areas used by breeding seabirds, creating direct competition that makes it harder for these birds to find sufficient food to support themselves and to raise their growing chicks. The competition for food also makes these seabird populations less able to cope with the myriad of other pressures to which they are exposed such as climate change, offshore renewable expansion, and avian flu.

Recent scientific advice recognised that the annually set sandeel quotas in the North Sea cannot ensure that enough fish remains available for marine species that depend on them. It highlighted the need for national management measures, noting in particular the needs of breeding seabirds which depend on food availability within proximity to their breeding colonies. Moreover, OSPAR Contracting Parties, including the EU, have committed to take urgent action to halt the decline of seabirds across the North East Atlantic in the current OSPAR Strategy. [2]

The UK’s progressive action to secure seabird’s food source is an important contribution to this end and it is incumbent on the EU and its Member States to support this. As seabirds know no borders, it is also essential that the EU and its Member States implement the necessary complementary measures within their own waters.

[1] OSPAR is an international convention through which 15 Governments & the EU cooperate to protect the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic.

[2] North-East Atlantic Environment Strategy (NEAES) 2030 (available at https://www.ospar.org/documents?v=46337)

Cover photo: ©James West

Lesser sandeel. Sandeels are nocturnal and typically spend all day covered in the sand. Photo: ©Yves Adams

Common guillemot (Uria aalge) eating their lunch. Photo: ©Piotr Poznan

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

Small phantom waders far away on the hunt for some delicious muddy worms, herons staring at you from the distance curiously observing every step you take. When you walk along the mudflats in Schansheide in Belgium, nobody would suspect that this area once was a mining quarry.

The transformation of this land is a testimony that nature can be restored and reclaimed as important habitats for birds and other species. The mineral extraction company Sibelco and our Partner Natuurpunt have a long-standing relationship that makes nature restoration projects like these possible.

In 2022, for their 150th anniversary, Sibelco handed over 35ha of land – a former quarry site near Antwerp – to Natuurpunt to maintain, transform, and manage. Now they are moving forward with just another milestone for nature. The Maatheide Blokwaters, an 18ha of former quarry land close to the Dutch border, was given to our Partner during the signature of an important charter between the two parties this October.

“Nature in Flanders is highly fragmented. Sibelco allows us to make extra efforts to strengthen local nature. In addition to setting up nature restoration projects with dry heathland and drifting dunes, the target species for this area are the smooth snake and natterjack toad which are European-protected species,” said Bart Vangansbeke, President of Natuurpunt.

In the long run, Maatheide-Blokwaters will become a nature haven for a variety of bird species such as the little Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula), the Great White Egret (Ardea alba), and the ‘near threatened’ Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus).

Sibelco and Natuurpunt have been collaborating since the 80s. What started as a simple access to the sites to monitor birds, became a strong and valuable relationship for nature. This is also due to the revamping of Sibelco’s sustainability strategy to focus on biodiversity. The relation gained momentum and the company started to hand over the maintenance and management of reclaimed quarries to restore nature properly.

The newly signed charter reinforces the pre-existing collaboration and common strategy, but it also marks an important milestone as a symbol to other industries. It is a chance to find new opportunities for a robust nature between the different quartz extraction phases. Natuurpunt and Sibelco are convinced that the cooperation can lead to important added values for nature and each other.

Partnerships like that of Sibelco and Natuurpunt are an important pillar in nature restoration and a great example of how coexistence between industry and nature can be possible through a joint effort. We cannot wait to see the observing faces of the Grey Herons (Ardea cinerea) and the pointy beaks of the Ringed Plover in the forthcoming scenic area of Maatheide-Blokwaters.

Cover photo: ©Yves Adams

Walk on-site in Maatheide-Blokwaters during the 150th anniversary event. Photos: ©Tom Cabuy

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

by Cyrielle Goldberg

Had you been wandering the corridors of the European Parliament on Tuesday 17th October at lunchtime, “nothing to report” is probably what would have crossed your mind – Eurocrats going about their daily business, the (alarmingly warm) Autumn air filled with the hum of conversations and the shuffling of footsteps. But behind the doors of the plenary session, as the votes of the day closed and concluded the final adoption of the new Fisheries Control Regulation, the seas had started to boil. Why the fuss, you may ask? One look at the timeline is enough to see that this is no small deed. In total, it will have taken five years for the European Commission, Council and Parliament to reach an agreement on how the EU fisheries control system should be revised, a highly needed change amid the escalating environmental crises that are crippling our oceans. Whether it is enough is however another question.

On the importance of effective fisheries control

Ocean-related affairs are, by nature, confronted to the tricky issue of information asymmetry – to put it simply, who knows what’s going on at sea? Coupled with inadequate control, this has been an open door for destructive fishing to go on killing nature at sea without any accountability. If the EU intends to reach the ambitions it has set for itself in the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) in terms of conservation and exploitation of marine biological resources, better control of its fishing fleets is therefore key.

The new control regulation does introduce interesting changes – of particular interest, we can cite the requirement to use electronic logbooks to record all catches, as well as the tracking of all fishing vessels on a continuous basis. The use of remote electronic monitoring systems (REM), which involves closed-circuit television cameras, sensors, and systems to store data on boats, is also a particularly welcomed addition.

However, while we recognise that this new piece of legislation is a step in the right direction, we cannot but deeply regret that our decision-makers didn’t seize it for the opportunity that it was: a much-awaited momentum to change the rules about how electronic monitoring systems can be used and to concretely rise to the EU’s outspoken ambitions, especially when it comes to tackling bycatch of sensitive species.

Bycatch or the seabird’s plight

Bycatch, or the incidental catching of species in fishing operations, is one of the most significant threats to seabirds, cetaceans, sharks, rays, and sea turtles. More than 200,000 seabirds are reported to be bycaught in Europe every year, among which at least 29 are threatened species listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive. For some time now, Member States have been required to reduce and eliminate bycatch under diverse binding obligations – the Birds and Habitats Directives, the Common Fisheries Policy, the Data Collection Framework, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, to name but a few. However, due to lack of data collection, reporting, and implementation, bycatch remains a pressing issue in EU waters and by EU vessels.

If the Control Regulation is what it brands itself – an enabler of fisheries control and an insurance of vessels’ compliance with the CFP – surely its revision should have tackled weak spots such as lack of enforcement in terms of bycatch obligations. But while the final text requires that bycaught species be electronically reported by fishers, it does not provide for any control mechanism to ensure that this rule is actually respected. Same goes for the requirement to use REM systems, which is narrowed to vessels of 18 metres length or more that present a risk of non-compliance with the landing obligation. This seems clearly off the mark when we know that small vessels account for 75% of the EU fleet and make up the majority of vessels that use gear which can present a high risk of bycatch.

Installing cameras only to support the implementation of the landing obligation – i.e. the requirement to land all catches and not discard anything at sea – won’t provide better bycatch data and won’t accomplish the objective of minimising bycatch as fixed in EU legislation. Same goes for relying on unplanned observations while carrying out other tasks onboard. Ensuring adequate monitoring and reporting of bycatch of sensitive species at EU level cannot go without a widespread use of REM.

Habemus REM

Luckily, the final text leaves us with a foot in the door, as it states that Member States have the possibility to use REM systems to control vessels’ compliance with rules of the CFP other than the landing obligation. No more excuses – Member States can take action to curb bycatch and support healthy seas by requiring all vessels to install and use REM systems for the purpose of identifying and monitoring sensitive species. Even for small boats where there isn’t enough space to host a heavy system like REM, Member States could support specific observers’ programmes where paid observers would be trained to identify sensitive species onboard and dedicated to that task.

It’s as simple as this: ambitions to curb bycatch will fall flat if they are not underpinned by the development of appropriate bycatch mitigation measures. Bycatch mitigation measures will not be developed if they are not informed by sufficient and accurate data. And as today’s sparse data collection shows, insurance that the data is actually being recorded and that it is reliable will only be obtained if fleets are equipped with tools that can control and identify exactly what is being fished and in which quantity.

Here again, we are left to rely on Member States’ good will to tackle the environmental crisis. At a time where an unprecedented amount and diversity of species is on the brink of extinction, it might be worth reminding our decision-makers that this is not only a chance to support science, but a moral imperative to act. Or else, let us rejoice at the fact that failure to reduce incidental catches of sensitive species is now recognised as a serious infringement under EU law.

Photo: John Fox

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

On their long-striving strolls through the wide wetlands of the Doñana, the flamingos can hopefully take their bath in peace again.

The Spanish and Andalucian governments finally came to terms and signed a joint agreement to abolish destructive agriculture methods, as well as to invest 1.4 billion Euros to support sustainable farming in the region of Doñana. Most importantly the previous plans to expand irrigable land around the Doñana National Park will not move forward, and be removed from the agenda!

The new agreement marks an important milestone for restoration efforts and shows that opposing political parties can and should come together to protect wildlife. Scientists, UNESCO, IUCN, the Natura2000 Network, and environmental NGOs, including our Partner SEO/Birdlife, tirelessly advocated for a change in the region and it seems that, after 21 months, their efforts are finally paying off.

“The success will depend on whether the results will be measurable and sustainable over time. So, this strong economic investment actually means the birth of a new Doñana, abandoning a bipolar state of protection-destruction that the region has endured for decades”, says Carlos Dávila, responsible for the Doñana Region at Seo Birdlife.

The Doñana Park is one of the 16 national parks in Spain. This precious wetland, and UNESCO World Heritage site, is an important habitat for migratory birds and a variety of endangered species, such as the Iberian lynx. Its position in the south of Spain with increasingly long droughts and intensifying agriculture demands has put pressure on the region for the last decades. The situation has worsened over the last years due to the negative effects of climate change and illegal water extractions. The fight over water became a fight on survival rights, nature vs farmers.

With a new framework for Sustainable Territorial Development, the government is trying to strike a deal that supports farmers and keeps the important habitat alive at the same time. In the long run, it will be important to control and evaluate conservation efforts and make sure that the environmental degradation will actually be reversed. Until then many NGOs urge the World Heritage Committee to enlist the region as a World Heritage site in Danger to ensure that all parties comply with the promises.

The Doñana Park finally has a chance to be reborn, and we need to make sure that the flamboyant strolls of the flamingos through the wetland in southern Spain can continue.

Photo: Shutterstock, imageBroker

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

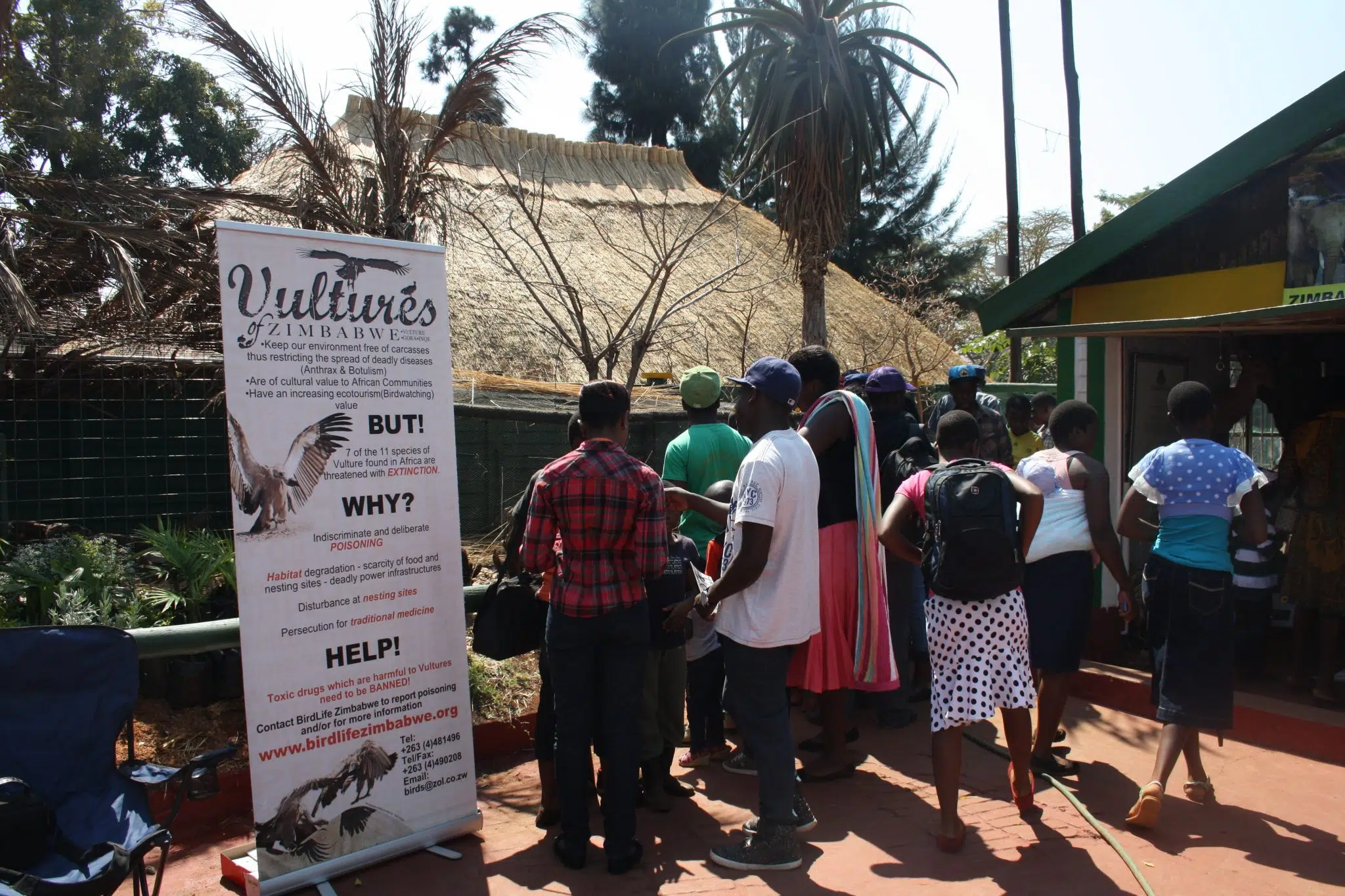

Conservation organisations play a critical role in advocating for the interests of local communities and in securing sustainable livelihoods. Despite this, local organisations in Africa often face challenges in securing long-term funding, and in building the skills and knowledge of their staff. This can limit their influence on political decision-makers, both at a national and regional level.

In order to strengthen Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and the BirdLife Partnership network in Africa, we are part of the project AfriEvolve: Capacity Development for Green NGOs in Africa. This initiative enables six African BirdLife Partners (or candidate Partners) to improve their knowledge and expertise in civil society cooperation and climate adaptation in smallholder agriculture. AfriEvolve has a three-fold objective: to increase organisations’ capacities through mutual learning, to improve regional and trans-boundary collaboration along with inter-regional networking, and to enhance Partners’ expertise in Climate Smart Agriculture, directly benefiting local farmers in six countries.

The Partners are formed into a West African and East African regional cluster. Clusters are conceived as regional southern-driven cooperation platform facilitating peer-to-peer or mentoring exchanges of knowledge, skills and resources in order to emulate capacity-building and political empowerment among its members. The six partner NGOs are also introducing Climate Smart Agriculture at six selected sites. Each of the project areas is located in significant regions for the country’s biodiversity.

Yala is Kenya’s largest freshwater wetland, measuring 20,756 hectares, and is classed as a Key Biodiversity Area. The papyrus swamps are home to rare Blue-breasted Bee-eater Merops variegatus and Papyrus Gonolek Laniarius mufumbiri, among others.

On top to the marshlands at the North-eastern end of the Lake Victoria, two mountainous regions in East Africa have been selected as project areas. The Echuya Forest Reserve is a highland forest landscape at an altitude of 2,570 metres in the heart of the biodiversity-rich Albertine Rift in western Uganda. The Albertine Rift is known for its variety of endemic animal and plant species that inhabit the remaining primeval forests.

In North-east Tanzania, the Usambara Mountains are located not far from the Indian Ocean coast and the border with Kenya, in the Tanga region. The mountains are partly covered with remnants of very old (more than 30 million years) forests and are of outstanding importance for nature conservation.

by Samuel Fournet

Above: beekeeping workshops with women in Côte d’Ivoire. Photo © SOS Forêts

In contrast, the project areas in West Africa are dominated by other ecosystems. Mole National Park is located in North-western Ghana, and is mostly formed of open savannah forests that are important wintering area for many migratory bird species, along with various mammals such as the African Elephant, Lion, Leopard and Bohor Reedbuck.

Azagny National Park in Côte d`Ivoire can be found 100 kilometres west of Abidjan, spreading 21,850 hectares along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea. With lagoons, evergreen primary forests, dry and wet coastal savannah, wetlands and mangrove areas, the park offers around 134 plant species and rare, endangered animal species such as Forest Elephant, Chimpanzee, Pygmy Hippopotamus, West African Manatee and Royal Antelope.

In Burkina Faso’s interior lies the Sourou Valley. With a total area of 20,926 hectares, this watershed, bordering with Mali, consists of broad floodplain marshes and acacia forests. Large parts of the area are dominated by agricultural land, where only trees of economic value remain. The valley is an Important Bird & Biodiversity Area, but the natural resources are under considerable pressure.

AfriEvolve is an initiative running from March 2021 to December 2023 implemented by Nature Kenya, Naturama, Nature Uganda, the Ghana Wildlife Society, Nature Tanzania and SOS Forêts. The Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU – BirdLife in Germany) coordinates the project and cofunds it with BMZ, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. A final learning catalogue product, including all key webinars and field practices, will be developed to disseminate and scale up the experience among the BirdLife network. This article draws up a general project introduction.

In the next newsletter, we feature the work of individual African partners participating in the AfriEvolve.

Latest news from Africa

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

This article is part of our Spring Alive programme, which aims inspire and educate children across Africa and Eurasia about the wonders of nature and bird migration. The 2021 Spring Alive season has been made possible with the continuing support of HeidelbergCement.

The 2021 Spring Alive season drew to a close in December. With COVID-19 restrictions lifted for many countries, our partners across Europe, central Asia and Africa were able to resume their usual programme of school lessons, outings and workshops. In the Autumn, we welcomed two brand new Spring Alive partners: Senegal and the Ivory Coast. The 2021 theme, “How should we protect bird nests?”, formed the focus of the activities throughout the year.

Spring Alive’s messaging mainly focuses on seven migratory bird species that breed in Europe and spend the winter in Africa: the White Stork, Collared Sand Martin, Barn Swallow, Common Ringed Plover, Common Cuckoo, European Bee-eater and Common Swift. However, Africa is also home to many resident species that breed there all year round – so it is still important for our African partners to spread the word on how to protect birds’ nests. Here are just a few African species that can benefit from our action, with advice that can be applied to breeding birds anywhere in the world. Why not make it your New Year’s resolution to give your local birds a helping hand this year?

by Jessica Law

The White-faced Whistling-duck breeds all year round across sub-Saharan Africa. Because it nests on the ground, its eggs and chicks are particularly at risk from predators, trampling and disturbance. If you want to help it raise its young in peace, try to stay on the path when going for a walk in nature, and keep to areas intended for the public.

The Speckled Mousebird is a common ‘backyard bird’ across Africa, and can nest at any time of year. If you spot one building its nest in your garden, give it a helping hand by letting your bushes and trees grow. The foliage will provide safe shelter for the nest – and plenty of building materials!

Little Swifts build their nests in cracks and crevices under roofs across Africa. But as buildings are repaired and modernised, the swifts are running out of homes. You can give them more real estate choices by putting up a nest box. Buy them ready-made or try your hand at making your own – there are plenty of great instructions online.

October is peak breeding time for the African Pied Wagtail across sub-Saharan Africa. The species likes to build its cup-shaped nests near waterways such as flooded grasslands, rivers and marshes. However, many of Africa’s wetlands are being drained to make way for agriculture or buildings. By supporting nature conservation groups, you can help protect the most important habitats for breeding birds.

The Grey Go-away Bird is named after its distinctive call, which really does sound like a person shouting “Go Away!” in English. When it comes to nesting, its call is particularly appropriate. If you get too close to nests, you could risk damaging them – even loud noise and disturbance could be enough to make parents abandon their nest. What’s more, you may be leaving a scent trail for predators to follow straight to an easy snack – so always keep your distance.

2022 will be an exciting year for Spring Alive. This spring, our new website will be launched, providing an updated platform for activities, teaching resources and news. The public will also be able to record their sightings of Spring Alive species on our interactive map as the birds migrate from country to country. This is particularly appropriate given the theme for this year, citizen science: a vital source of data that is becoming a growing force in bird science and conservation.

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

The scene is a grim one: rangers wearing protective gear paddle out in a dinghy to the middle of Hula Lake, Israel, to start retrieving the dead Common Cranes scattered across the water. Their job is cut out for them: more than 5,000 cranes succumbed to the recent bird flu outbreak, which hit Israel in December 2021.

“The first signs of a massive event appeared in wild birds around 12-13 December,” says Yoav Perlman, director of SPNI (BirdLife in Israel). “The epicenter is in the Hula Valley. However, in recent weeks more and more cases have been found elsewhere in the country, with a higher ratio of non-cranes, including raptors such as Common Buzzards and Eurasian Kestrels.”

Israel’s Environment Minister Tamar Zandberg called the incident “the worst blow to wildlife” in Israel’s history – but the outbreak has also affected domesticated birds. Local farmers have had to cull half a million chickens, causing serious loss of income and even prompting fears of egg shortages. But what is this virus, and where did it come from?

There are numerous different strains of avian influenza, or ‘bird flu’. Most are benign, at worst causing only mild disease, and circulate in wild birds. Under the crowded conditions of intensive poultry rearing, however, some variants can evolve into “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza” (HPAI) viruses, which can cause massive mortality in poultry. The strain H5N1 is of particular concern. It is primarily a poultry disease, but can impact wild birds too.

“H5N1 is responsible for the outbreak in Israel, and is similar to the strain that hit Barnacle Geese in Scotland recently,” explains Perlman. “From what I know, the first Avian Influenza cases in this outbreak in Israel were identified in poultry farms and only later in wild birds. However, with large-scale outbreaks across Europe just before Israel, one could speculate that wild birds migrating south from Asia and Europe carried the disease with them.”

When the scale of the problem was realised, the State of Israel declared it a national security crisis based on the risk to the poultry industry and to humans. So far, action has focused on disposing of bird carcasses and closely monitoring the spread of the epidemic. However, according to Perlman, it took the authorities far too long to spring into action, which may have increased infection rates in the Hula Valley.

“I think that 10 precious days were lost, maybe more. However, since the carcass removal process commenced second half of December about 80% of carcasses have already been cleared,” he says. On a more positive note, SPNI is uniquely placed to offer their help. “We are using our network of birders – both staff and volunteers – to detect dead or dying birds, and report them promptly via a specialized system,” explains Perlman.

SPNI staff are also present on-site in Hula Valley, aiding the clean-up operations and advising the government as part of a national panel of experts. After the crisis is over, they will continue to advise on how to address and prevent future incidents, including whether to amend bird feeding practices at Hula Lake to prevent large numbers congregating and spreading disease.

Above: Hula Valley is important rest stop for the Common Crane on its migration south to Africa © Oren Valdman

“We are using our network of birders – both staff and volunteers – to detect dead or dying birds, and report them promptly via a specialized system.”Yoav Perlman, director, SPNI (BirdLife in Israel)

Alongside 27 European countries impacted by the outbreak, the UK is experiencing its largest ever outbreak of bird flu, which has led to 500,000 poultry and other domesticated birds being culled in recent months. Since the start of November, an avian influenza prevention zone had been declared across the country, requiring strict biosecurity measures and all captive and domesticated birds to be kept indoors.

One of the most notable wild casualties was a rare White-tailed Eagle found dead on the Isle of Skye – thought to be Scotland’s first ever case of avian flu detected in an eagle. Researchers believe the raptor may have fed on infected Greylag Geese.

In addition, Martin Fowlie of the RSPB (BirdLife in the UK) says: “We are very concerned about the large number of deaths of Barnacle Geese on the Solway Firth, Scotland. This number is now estimated to be in excess of 4,000 birds, with some estimates suggesting that between 15-20% of the Svalbard Barnacle Goose population has died.”

He adds: “The RSPB is following the government guidance on our reserves, implementing biosecurity measures to minimise the spread of disease. Surveillance and monitoring is crucial to not only help understand why this outbreak is so large, but also to look for potential population impacts on species severely affected. People finding numbers of dead wild birds should report them to the relevant government authorities.”

We’ve seen the worrying impact that bird flu can have on wild birds, as well as the measures required by the poultry industry to ensure adequate biosecurity – but what is the risk to humans? Fortunately, so far it is relatively low. The virus has been known to jump from birds to humans in where there is extensive close contact, usually on poultry farms, with an infection reported in the UK last week from someone who had regular close contact with infected domesticated birds. However, it cannot spread from person to person, so is unlikely to cause a global pandemic like that driven by COVID-19.

Globally, from January 2003 to 30 December 2021, there were 863 cases of human infection reported from 18 countries. Of these, 456 were fatal. But according to the World Health Organisation, despite this winter’s surge, “The overall pandemic risk associated with [H5N1] is considered not significantly changed in comparison to previous years.”

Nevertheless, citizens are advised to keep their distance from birds that look ill or distressed, and to thoroughly wash their hands after refilling garden bird baths and feeders. Regularly cleaning this equipment is also necessary to stop disease from spreading between birds. Furthermore, the UK’s Chief Vet Christine Middlemiss told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “If you keep chickens and you want to feed wild birds, you need to make sure that everything is completely scrupulously clean and absolutely separate so that you don’t take infection into your own birds and make them sick.”

Applying effective biosecurity in the poultry industry is the primary requirement to control H5N1 bird flu. However, in the last big outbreak of 2006, authorities in some parts of the world proposed attempting to control the spread of bird flu by culling wild birds, destroying their habitats, or displacing them from breeding and roosting grounds. Such measures are ineffective and could often make matters worse, as well as distracting from more suitable interventions. They also add to the stresses already imposed on many species by habitat loss.

“The main conservation concerns are around calls to cull wild birds, and blaming wild birds for the problem rather than ineffective biosecurity measures in the poultry industry,” says BirdLife’s Chief Scientist Stuart Butchart. “BirdLife Partners worldwide are monitoring the situation and continuing to advocate for the protection of wild birds.”

“The main conservation concerns are around calls to cull wild birds, and blaming wild birds for the problem rather than ineffective biosecurity measures in the poultry industry.”Stuart Butchart, Chief Scientist, BirdLife International

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.