What’s the catch? The fate of Europe’s seabirds

Bruna Campos explains why a ‘sea change’ in policy is needed to protect thousands of Europe’s seabirds from the threat of incidental bycatch in fishing gears.

By Bruna Campos

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”, Shakespeare famously wrote – and though the great playwright was reflecting upon the power of princes, at BirdLife these words turn our thoughts to the plight of petrels…and shearwaters, and the seabirds that together carry the unwanted crown anointing them the most threatened bird group in the world.

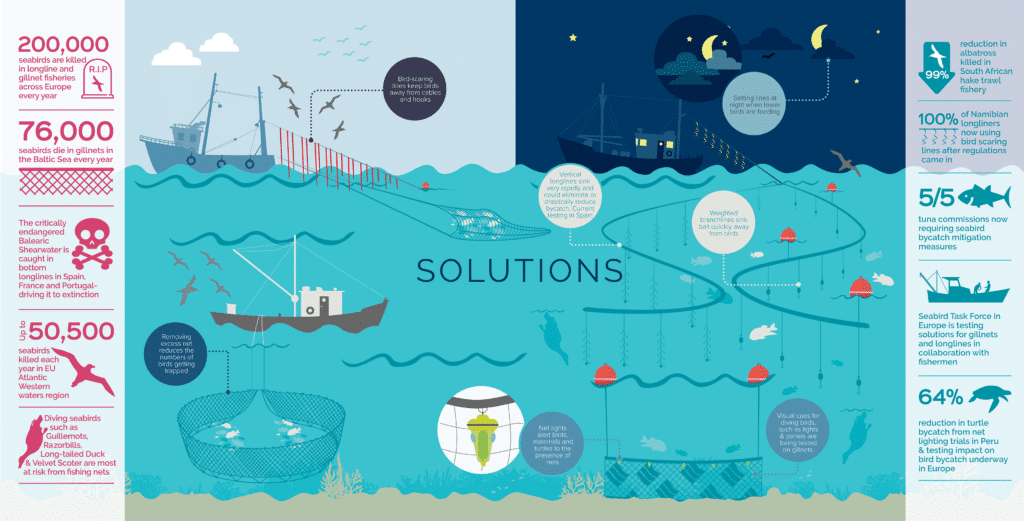

Marine biodiversity is facing enormous pressure from a wide range of human activities that lead to habitat destruction and pollution. And a huge part of the problem is seabird ‘bycatch’, with an estimated 200,000 seabirds accidentally caught and killed by commercial fishing hooks and nets each year. Many of Europe’s 82 seabird species are at risk, but some species seem to be far more susceptible than others – for example, Steller’s and Common Eider, Long-tailed duck and Velvet scoter are regularly caught in gillnets in the Baltic, while Northern Fulmar and Great shearwater are menaced by demersal longline fishing off the coast of Western Scotland, Ireland and France. It is particularly alarming that already threatened species are being put into further peril; such is the case for several seaduck species (in dramatic decline in recent years) and also for the Balearic shearwater – Europe’s most threatened seabird.

“…an estimated 200,000 seabirds [are] accidentally caught and killed by commercial fishing hooks and nets each year.”

Out at sea, BirdLife’s conservation team and our ‘Seabird Task Force’ are working with fishermen to overcome practical challenges through pioneering technical innovation. Nonetheless, bycatch of seabirds – and also many marine mammals and sea turtles – continues despite existing EU regulations. Improvements are clearly needed here on dry land before we will see a sea change in our fisheries.

Until recently, the concept of managing fisheries focused almost exclusively on quotas – the amount of fish that can be taken from a fish stock (i.e. a subpopulation of a particular species of fish) – and, to a far lesser extent, what size of fish may be caught. This approach, however, completely ignored the rest of the marine environment and critical issues such as seabird bycatch.

In recognition of this, the 2013 reform of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) set out a path that would ensure: new financial incentives to encourage fishermen to adopt seabird bycatch mitigation measures; new measures to ensure regulated and controlled management of vessels against seabird bycatch; as well as new data collection rules obliging governments to annually determine the number of birds accidentally caught within their fisheries. While incentives and data collection rules are now in place, the debate over new ‘technical measures’ for fisheries management is ongoing.

Earlier this year, the Commission proposed minimum standards for fisheries management in every sea basin across the EU (including bycatch mitigation measures in some sea basins). Member States would then be free to decide whether they would (and to what extent) go beyond these minimum benchmarks. However, representatives of EU national governments – sitting in the EU’s AGRIFISH council – promptly removed all minimum standards to tackle seabird bycatch from the proposals and also the possibility of having regional enhancements.

While this is a major setback, the regulation is not dead in the water – at least not yet. In early October, the Fisheries Committee of the European Parliament will vote on whether it agrees to delete these minimum standards. It is expected that MEPs will rightly vote for better rules, and EU national governments will have to negotiate these with the Parliament.

So much depends on this vote – if minimum standards are not adopted across EU waters, we will almost certainly have to wait ten years for a second chance. The question is – can Europe’s threatened seabirds afford to wait ten years? In the case of the Balearic shearwater, the answer is a heartbreaking ‘No’.

Bruna Campos – EU Marine & Fisheries Policy Officer, BirdLife Europe & Central Asia

![]() Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe.

Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe.

Image credits: Seabird bycatch © David Grémillet

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |