Your Excellency Mr. Huang Runqiu, distinguished delegates, it is my pleasure to speak to you on behalf of Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, the Wildlife Conservation Society, WWF International, and my own global BirdLife International family, present in 115 countries.

We know, you know, nature is in crisis. The science is unequivocal. Our very survival is at risk, as well as that of entire ecosystems and more than a million other species. The biodiversity and pandemic crises are in deadly lock-step with the climate crisis.

We all know and agree we need, we demand, a strong post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. This must set and achieve clear, measurable milestones and targets to achieve a mission of being nature-positive – that is, halting and reversing the loss of biodiversity – by conserving and restoring it by 2030. This means concrete, specific numbers starting now, with scrutiny along the way as to how we’re doing – it isn’t acceptable to wait for 10 years and then look surprised when we didn’t get there.

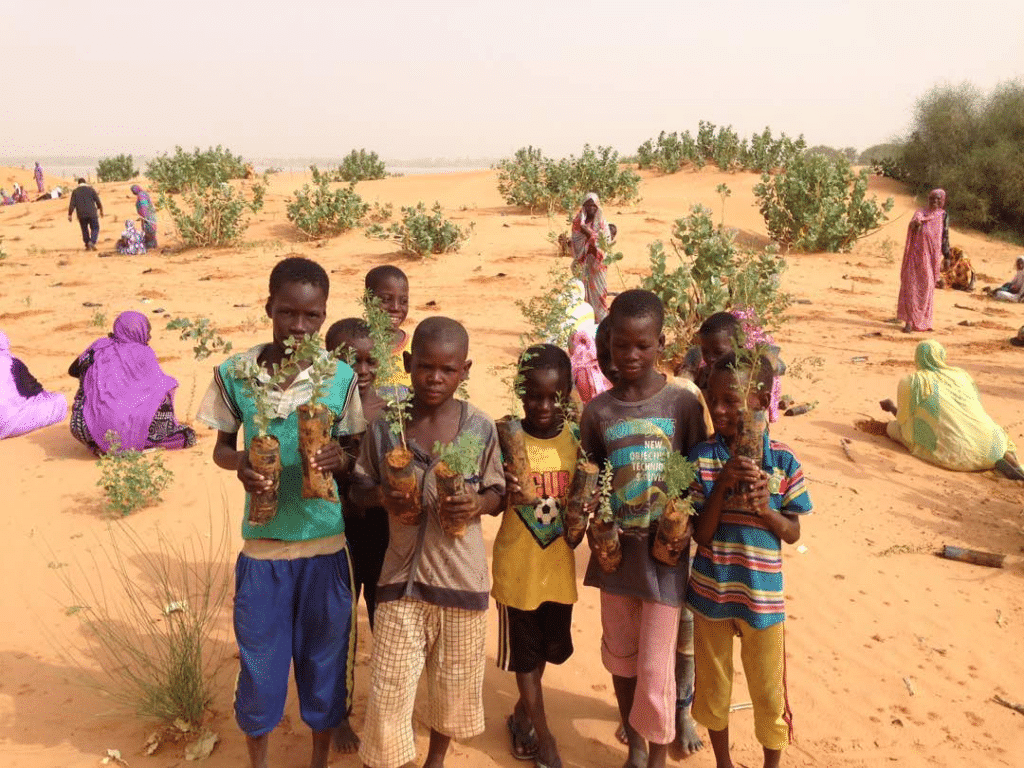

We must not equivocate – we must now conserve and restore the world’s key biodiversity areas, the integrity and intactness of its ecosystems and its incredible diversity of species – as a win/win/win solution to the biodiversity, climate, and health crises. Through measurable targets such as the effective protection and conservation of at least 30% of land, freshwater and sea by 2030 – working with and for local people, with priority given to Key Biodiversity Areas which provide life sustaining ecosystem services.

Let us listen and learn from the Indigenous Peoples and local communities who know and treasure their landscapes and seascapes best. Let’s join forces with them, respecting and honouring their rights and wisdom.

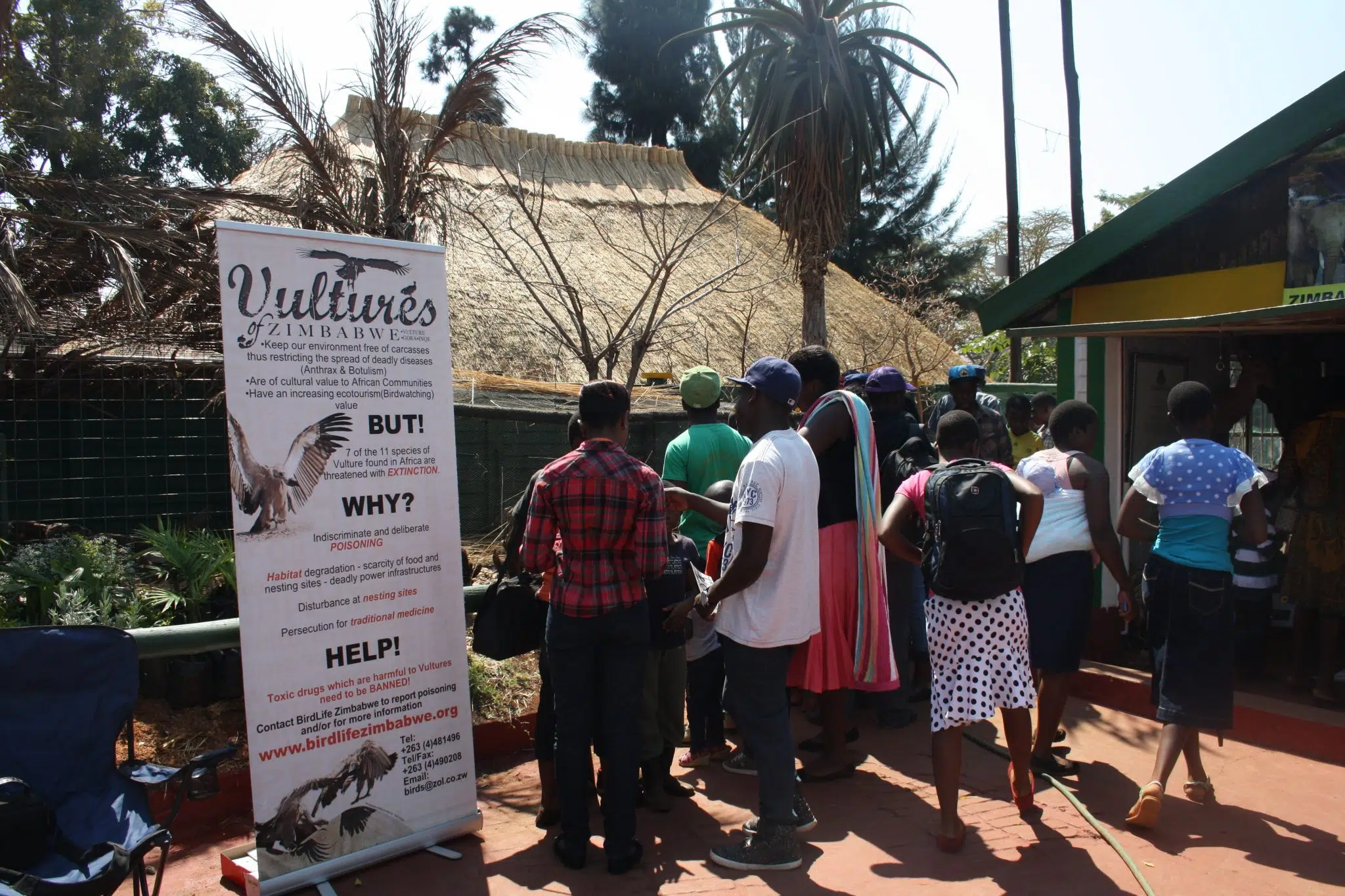

Conserving and restoring nature is just one tool in the toolkit, and unfortunately will not be enough unless we effectively address the drivers of nature loss. We know what they are: unsustainable agriculture and fishing, wildlife exploitation, unbridled destruction of forests, wetlands, and grasslands and climate change. And we know how to do this – there are many successful examples of sustainable use and management of nature to meet human needs for food, fibre and other commodities.

We must seize this opportunity and impose nature at the heart of inclusive, sustainable and just nature-positive economies by collectively closing the biodiversity finance gap. Government commitments, unlocking private sector financial flows, and ending harmful subsidies are the bottom line. Right now, we have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to drive the trillions of dollars being mobilised to build back better, to build back greener, bluer and more equitably after COVID-19.

Now must be the turning point where we stop trashing and destroying nature — now is the moment to overwhelmingly redress our dangerously unbalanced relationship with the planet and demand from ourselves, our governments, all players, action, not words. Many young people have a finely-tuned ear for what they call blah-blah-blah. My daughters have an uncanny ability to see through our words. Let us prove them wrong. Prove to my daughters, and your children and grandchildren, that transformational change is not empty words but concrete and measurable actions in our daily lives, and our daily acts. Ambitions and aspirations won’t save nature alone, won’t reverse climate change, and won’t prevent the next pandemic– only action will.

Just last week we and 1350 other civil society organisations called for the UN Human Rights Council to recognise the right to a healthy environment – and following its resounding support, we must now reflect this right in the global biodiversity framework.

We international conservation NGOs are fully committed to working with you to turn these words into reality, to create and then implement a global biodiversity framework that defines a generation and secures our planet’s nature for us and future generations – and we commit to hold you and ourselves accountable to these promises.

It is nothing short of a moral obligation. Humanity and nature are at a tipping point – there cannot be further delay.

Let’s fight together for justice for nature, the planet, and her people. We are in this together!

Gracias 谢谢