Connecting the dots

In BirdLife’s Atlantic Forest Programme, restoring ecological connectivity and thereby recovering overall forest health basically boils down to two interweaving threads: joining one forest fragment to another, and working with the right people.

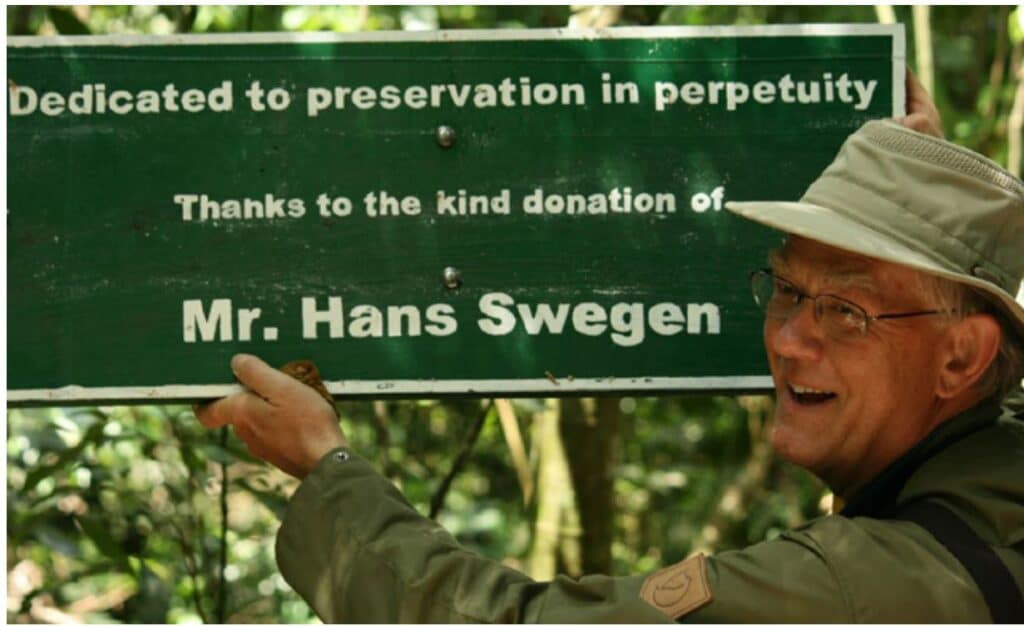

In the northern reaches of the biome, SAVE Brasil helped establish and support the management of the 6,000-hectare Murici Ecological Station and purchased 360 hectares of Atlantic Forest in the 100-km distant Serra do Urubu, where a private reserve was established. With these two strongholds, SAVE is now designing a Serra do Urubu-Murici forest corridor to connect existing forest patches between the two sites, and prioritise areas for forest restoration.

There are essentially two ways to restore a forest: you can fence off forest fragments and let nature do the rest, or you can plant native plant seedlings and monitor them to ensure optimal survival rates and actively reconstruct the original habitat. In many cases, a mixed approach is used.

‘Jump starting’ forest recovery with active restoration gets things moving but is expensive. Passive restoration is cheaper, but it takes a long time. SAVE Brasil is doing both, having started restoration activities within the Murici Reserve, and helping to establish a network of native plant nurseries, seed collectors and knowledgeable individuals to deliver and monitor restoration efforts in the region.

When the idea is to restore the natural flow of things, nature always helps out: planting more trees effectively attracts more birds and insects, which then actively take over much of the required ecological ground work to regenerate the ecosystem.

Even with help from the birds, forest restoration is a massive endeavour that can quickly exhaust resources. Nor is it guaranteed to work, especially if conservationists fail to consider the presence of human residents and their activities. In the Atlantic Forest, this typically means farmers and livestock producers.

“We want to encourage a system that combines agriculture, animal rearing and forest restoration, and generates mixed-revenue streams to help keep forests standing,” says Alice Reisfeld, SAVE Brazil Program Manager. “We expect this approach to have measurable benefits for the livelihoods of local landowners.”

Matters can get complicated when the landowners involved are reticent, even when the dialogue is about sustainable production practices that will benefit them. “Many landowners are not aware of the possibility of raising crops and cattle in a more sustainable way that will increase their productivity and help them access new markets, while also generating environmental services,” says Bárbara Cavalcante, Co-ordinator of the Northeast Atlantic Forest Project, SAVE Brasil. “That’s why we will implement demonstrative units in a few properties, so that others can also learn and allow replication of this model.”