Northern Bald Ibis: baldly leading the way in ibis conservation

Four ibis species in three very different circumstances. All facing extinction. One, the Northern Bald Ibis, is now recovering. What does it take to turn the tables on extinction?

By Shaun Hurrell

With the setting sun still warming a sandstone ledge on Morocco’s west coast one evening in November, a bulky bird tenderly preens its partner’s feathers using its long, scythe-shaped beak. As its black neck feathers catch the sea breeze, this Northern Bald Ibis is oblivious to the recent news regarding its entire species: on 22nd November 2018, BirdLife celebrated the improved fortunes of the Northern Bald Ibis as we declared its downlisting from Critically Endangered to Endangered. Thanks to sustained conservation efforts, wild colonies in Morocco are doing so well that the species’ population is on the rise.

For conservationists putting in hard graft for this ibis (for as much as 24 years in the case of Chris Bowden, now Coordinator of the AEWA Northern Bald Ibis International Working Group,) it was an emotional moment: “The ultimate accolade for a conservationist working to save endangered species is to contribute to improving the threat status of a species,” he says.

But what did it take to turn the population decline of the Northern Bald Ibis into an upcurve? It’s an important lesson to learn, because three other Critically Endangered ibis species also need all the help they can get. We will name this select group – which includes the Dwarf Ibis endemic to São Tomé, and the Giant Ibis and White-shouldered Ibis found mostly in Cambodia – ‘the downcurves’, not only because of the characteristic shape of their beaks, but because over the course of their history, they have also suffered human-caused population declines with the graphs to grimly match. Yet, despite differing circumstances of ‘the downcurves’, hope can be gleaned from some surprising similarities to Morocco’s story of conservation success.

The ‘old man’ of conservation

The first part of the Northern Bald Ibis’s scientific name Geronticus eremita means ‘old man’, owing to its unusual bald head. But ‘old’ certainly doesn’t have to mean lacking in vitality or strength. The species was listed in the highest category of threat for more than three decades: once widespread across northern Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe, habitat loss, pesticides and hunting drove the Northern Bald Ibis down to a small and dwindling wild population, mainly confined to just one breeding colony in Souss-Massa National Park, Morocco. At its worst, after a mystery die-off in 1996, just 59 pairs existed in the wild.

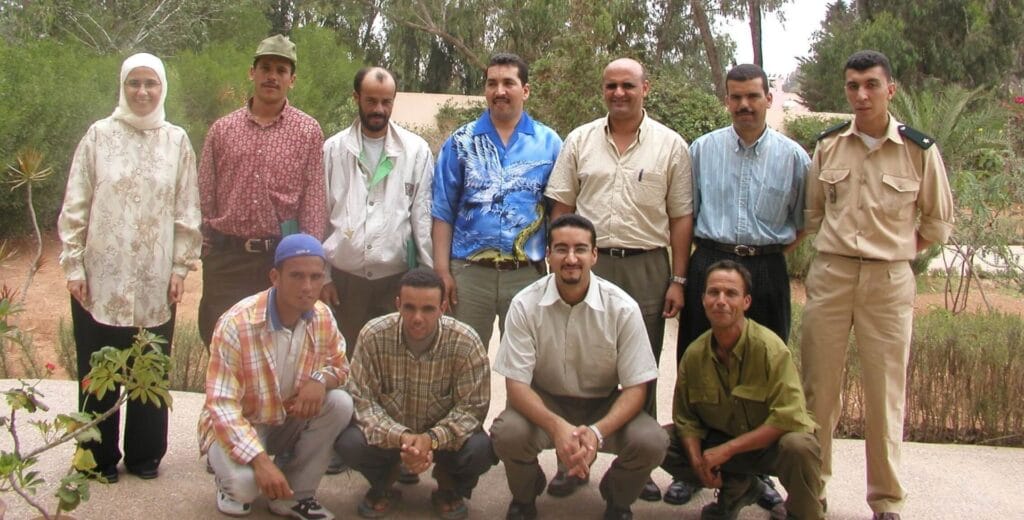

The task must have seemed insurmountable, but one has to start somewhere. Protecting the breeding and feeding areas of the remaining colonies was clearly the first step and Bowden, working for the RSPB (BirdLife in the UK), basically dropped everything and flew to Morocco, living there for over seven years based within the National Park. An early priority for the park and his team was to instil in local communities the “unique value of these rather bizarre-looking birds”, and actively recruit young wardens from the fishing villages adjacent to the colonies.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter!

“I used to spend hours talking through the importance of daily monitoring with Mohammed El Gadrouri and Abdallah Essamar [the first wardens] in what can only be described as a sandstone cave, overlooking the cliff-ledge colonies. They’ve become the best of friends, and are still stalwart ibis wardens today.”

The wild Northern Bald Ibis population has now risen to a modern-day record of 170 chicks fledged this season, with a total population of at least 708 birds (up from 589 in 2017). With the Souss-Massa colonies swelling, the ibises even started to spread along the coast, with two new sites and some isolated pairs discovered in 2017. “The consistent presence and dedication of the team of ibis wardens at the Moroccan colonies and roost sites has been absolutely crucial, and this news is above all a tribute to them,” says Bowden. “And the fact that the wardens are now supported directly by the National Park is tremendously important.”

“Without the creation of Souss-Massa National Park in 1991, there would have been little hope for the wild population,” says Jorge Orueta, SEO/BirdLife Spain, who has worked passionately for the species since 2000. But the Park wasn’t enough on its own – BirdLife ensured a network of NGOs would support the Moroccan government to research what was needed and manage the key areas for the ibis, in what became a decades-long relay of conservation effort. This started in the mid-90s with the RSPB, then with SEO/BirdLife – and more recently GREPOM (BirdLife in Morocco) – taking over the ibis baton.

“This network helped everyone to understand the key issues facing the species, and keep focusing on addressing them,” says Bowden. “And we’ve been fortunate in having continuous and positive interest of several key players – including Mohammed Ribi, Director of the National Park when BirdLife action began who, along with others, has also played a vital role.”

Whilst this is certainly a conservation win, we can’t relax. Downlisting to Endangered doesn’t mean ‘saved’; by definition the species is still ‘at very high risk of extinction in the wild’. The latest breeding sites – where ibises have cleaned cliff ledges and delicately started nest-building – are fragile. “The majority of the Moroccan ibises are inside protected areas, but these sites of new reproduction attempts are not,” says Khadija Bourass, Executive Director of GREPOM. The longest-standing colony outside the park, at Tamri, has some basic protection administered by the Forestry Department (as a formal ‘no hunting’ area watched over by wardens, on land that can’t be sold easily), but more comprehensive and meaningful protection has been a long-standing issue that still needs work – an urgent priority that’s emphasised in the ibis’s International Species Action Plan.

Also, lest we forget, the entire eastern population of the Northern Bald Ibis is thought to be extinct in the wild. Whilst a semi-captive population in Turkey is going from strength to strength, the project has been waiting for war in Syria to end, so the birds can be released to migrate safely south towards Ethiopian wintering grounds. Meanwhile, the last few remaining truly wild birds that know the route instinctively are thought to have been killed, though some hope remains and Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society (EWNHS, BirdLife in Ethiopia) will be on the look-out this coming season.

The celebration is still justified despite the eastern population, however. What the ‘old man’ of conservation has taught us is that what’s being done in Morocco is working very well indeed. And in order to see continued success, we mustn’t stop. “Targeted action does help bird species to recover,” says Dr Stuart Butchart, BirdLife International’s Chief Scientist. “But the trends in bird populations globally are negative, showing that much greater efforts are needed to replicate such successes more widely.” Thus, in terms of membership to ‘the downcurves’, for now we can (and should) celebrate the Northern Bald Ibis as one ‘up’, three to go.

The forest dwarf

“There!” exclaims Hugo Sampaio. A glossy sheen of bark-brown and shade-leaf green is caught by a ray of light breaking through dense forest canopy, giving away the silhouette of the bird he’s here to see. The tropical humidity of Obô Natural Park is a far cry from Morocco’s desert and surf-sprayed cliffs, but here in São Tomé island’s lowland rainforest – or what’s left of it – is the habitat of the Dwarf Ibis Bostrychia bocagei, a smaller cousin of the Northern Bald Ibis. According to Sampaio from SPEA (BirdLife in Portugal), who spent months on a BirdLife research expedition surveying São Tomé’s endemic birds, despite the dark forest, this ground-feeder is one of the first – and easiest – endemic birds to spot, tending to erupt onto a low branch when people approach. This is great if they’re ornithologists or eco-tourists, but a problem if they’re hunters who haven’t found any pigs.

“Hunters are travelling deeper into the forest to hunt feral pigs,” says Jean-Baptiste Deffontaines, Manager of a new BirdLife project in this volcanic island nation of São Tomé e Príncipe, found 250 km west of the central African coast. “They’re not targeting the ibis, but will take a few on their way back if they’re unsuccessful – which is increasingly common.” The hunting of ibis is just one consequence of an expanding human population on São Tomé. In the primary lowland forest of Obô Natural Park and its buffer zone – prime ibis habitat – timber houses are being built, illegal logging is rife, and a perfect ibis breeding area has already been lost to oil palm plantations. “Palm oil is small-scale here,” says Deffontaines, “but on an island of just 700 km² it’s a big deal – taking up 12% of the land since 2006.”

Of ‘the downcurves’, the Dwarf Ibis is perhaps most at risk from a sudden and catastrophic decline in its population, because the entire species is now confined to just 65 km² of breeding habitat (half the size of what was previously estimated until Sampaio’s expedition). This means that any hope for saving the species mainly hangs on rapidly saving remaining primary lowland forest, while ensuring that ibis hunting stops. More research into the ibis’ breeding ecology is needed too, says Sampaio, because the effect of other potential threats is unknown, such as introduced mammals.

“As we saw in Morocco, a protected park is crucial to safeguard a species’ habitat, but not always enough to save every species in it,” says Roger Safford, BirdLife’s Preventing Extinctions Programme Manager. “To achieve this, specific threats (like illegal hunting) must be dealt with explicitly as part of the overall management.” There are many reasons for optimism, however. “We’re in it for the long haul,” says Deffontaines. With €2 million for five years invested though BirdLife and a consortium of partners from the EU’s ECOFAC programme (for the conservation and sustainable management of Central African forests), the project is taking a ‘landscape-approach’ to solving the issues facing Obô Natural Park and – crucially for the ibis – its surrounding buffer zone too.

Deffontaines is keen to stress that this means looking at the big picture whilst protecting São Tomé’s endangered species – from working with the government to manage the Park (like in Morocco), to tackling species-specific threats on the ground, whilst also ensuring people’s livelihoods are considered throughout, and actually improved.

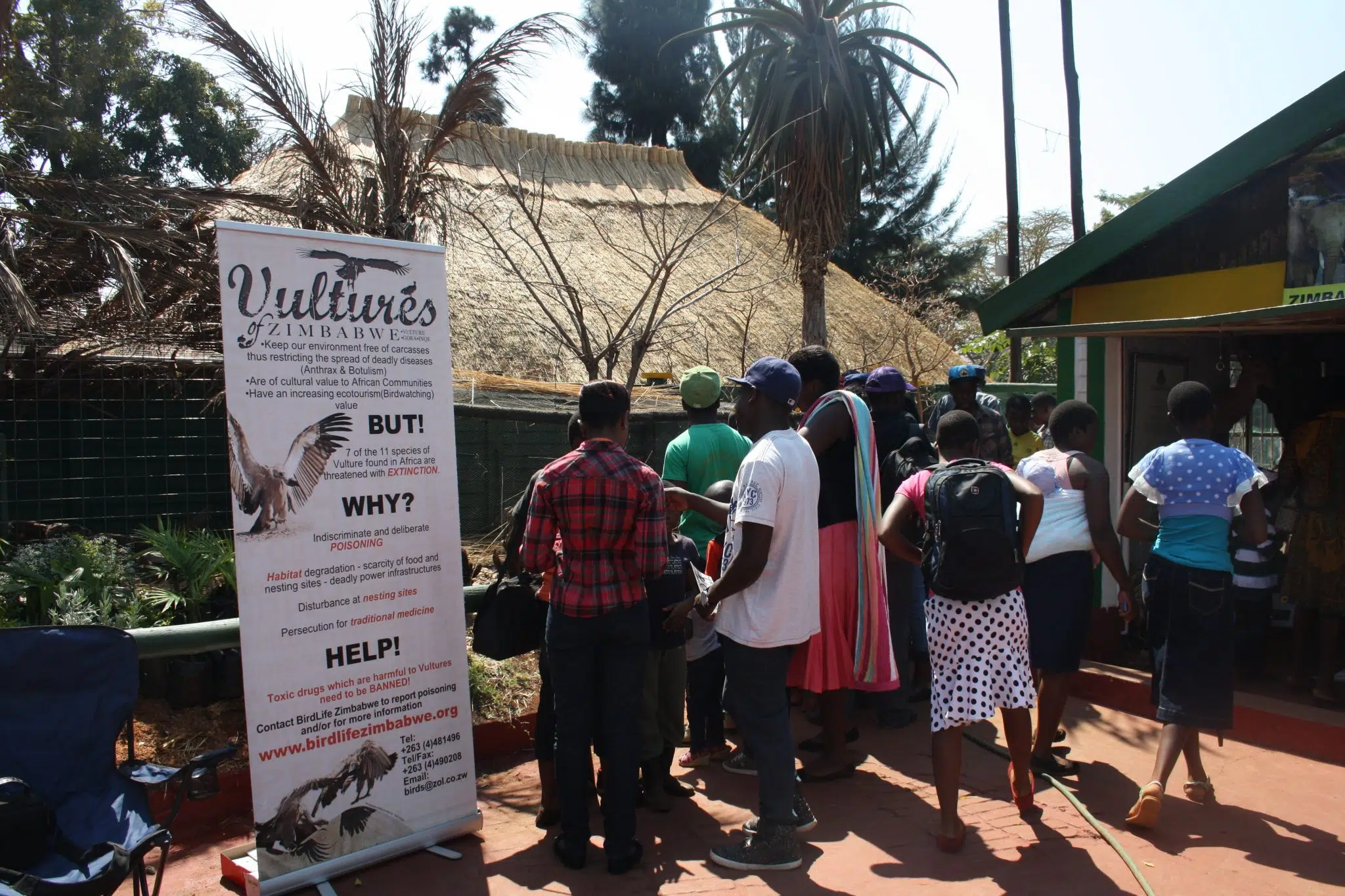

“We need to be present in the park and enforcing new rules, but in a way that we are still seen as the ‘good guys’,” says Deffontaines. The capacity of environmental NGOs is quite low in the country – something BirdLife is working hard to improve – and studies have shown a low level of environmental education in São Tomé, particularly amongst rural populations. Thankfully, community outreach work by SPEA and Oikos is already infusing pride in the area’s endemic wildlife here, and there are lots of new activities planned, including developing ecotourism to bring an alternative income to local communities. In a parallel to Bowden’s work in Morocco, the project is also investing locally to hire and train a team of 15 local ‘Eco-guards’, and implementing new management-orientated monitoring systems. The project also aims to formally protect the park’s buffer zone.

Will it be enough to save the Dwarf Ibis from extinction, though? “I feel we’re on a good run”, says Marquinha Martins, the project’s new Field Officer, who is part of a new generation of São Toméans that studied abroad. She returned to put her conservation knowledge into practice, and is now in charge of monitoring the work of the Eco-guards. “If all goes well with each line of work working together – protection, research, community engagement, ecotourism – then we can not only protect our ibises, but we can show the great value of this work and this park to the benefit of the people,” she says.

Putting the ‘downcurves’ on an upcurve

Across the world, Martins’ words couldn’t be more relevant. At the edge of Western Siem Pang Wildlife Sanctuary, northern Cambodia, a massive Giant Ibis Thaumatibis gigantea sits proud in a spindly tree preening its feathers overlooking a jasmine rice paddy, whilst deep within the protected area, a White-shouldered Ibis Pseudibis davisoni probes its beak into damp mud beside a forest pool that only a few days before had been on the cusp of drying out in the summer heat – that was, until a group of local people arrived with spades to rejuvenate it, thanks to community outreach work and payment from the BirdLife Cambodia programme.

These scenes epitomise BirdLife’s work at Western Siem Pang, where management of the protected area uses inclusive approaches that benefit both nature and people. It’s worthy of another article entirely, but here reinforces that when it comes to saving ‘the downcurves’ (or any species on the edge of extinction, in fact, says Safford) there are a few key tried-and-tested conservation themes that are required for success.

Number one is working with governments to officially protect and manage habitat – something BirdLife was instrumental in for Siem Pang after many years of effort. But as we’ve seen, that may not be enough on its own, especially when specific threats jeopardise the rarest of species – think colony disturbance at Souss-Massa, hunting in Obô and, in the case of Siem Pang, the drying of the forest pools that ibises rely on, or the felling of forest for illegal logging and expanding rice paddies. Thus, the second, and perhaps most important element of many BirdLife projects is the tailored work that we do with, and for, local communities to generate benefits for them whilst tackling specific threats – be it education and outreach, via employment through projects, as with Souss-Massa’s wardens or Obô’s Eco-guards, or alternative livelihood schemes, such as ecotourism, or Ibis Rice in Siem Pang. Get it right, and a species and its habitat will have a chance.

Will these measures be enough to put all ‘the downcurves’ on an upcurve? “In five years, we hope to have great results with direct action for the Dwarf Ibis,” says Deffontaines. Sustainable protection of the entire Obô Natural Park and its buffer zone will likely take longer, as will securing the fate of Cambodia’s ibises, but as we’ve seen with three decades of conservation effort for the Northern Bald Ibis, it can work.

With thanks:

A key element to saving species is reliable funding. We’re grateful to the following for their support: For Northern Bald Ibis: Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation and Zeiss (BirdLife Species Champions for Northern Bald Ibis); the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF); Gaia Zoo for supporting SEO/BirdLife Spain; SEO, RSPB and VBN (BirdLife Netherlands) for supporting GREPOM’s ibis work. For São Tomé: funding from the European Union through ECOFAC 6, the Rainforest Trust, Synchronicity Earth, the Prentice family (Species Champion for the Dwarf Ibis), Disney Worldwide Conservation Fund, and the US Fish & Wildlife Service. Future community engagement work will be led by Oikos with support from BirdLife and SPEA. Direct funding and technical and fundraising support for both São Tomé (through SPEA) and Northern Bald Ibis in Morocco has been provided over a long period by RSPB. For Western Siem Pang: the Darwin Initiative, the MacArthur Foundation, Fondation Segré, and Species Champions Stephen Martin (Giant and White-shouldered Ibis) and Giant Ibis Transport (Giant Ibis).