Header Image: Most of the world’s terrestrial KBAs already contain infrastructure, and more are likely to in the near future © BlackCat Imaging/Shutterstock

By Liam Hughes

When you think of the most important sites for nature, thoughts are likely to spring to remote, pristine wildernesses. Perhaps a tropical rainforest, the symphony of chirping cicadas and birdsong an indication of the teeming diversity deep within its undergrowth. Or maybe a wetland, with large flocks of birds soaring over the water’s surface as they search for resources found in the rich ecological communities hidden beneath the water’s surface. What probably doesn’t immediately come to mind are man-made structures.

However, a new paper led by BirdLife scientists in collaboration with researchers at WWF and the RSPB (BirdLife in the UK) is a stark reminder of our ever-increasing footprint on nature, with infrastructure being found in approximately 80% – or more than 12,086 – of the world’s terrestrial Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). The study was the first assessment of the presence of infrastructure within these internationally important sites for nature, and worryingly suggests the figure is likely to significantly increase in the future.

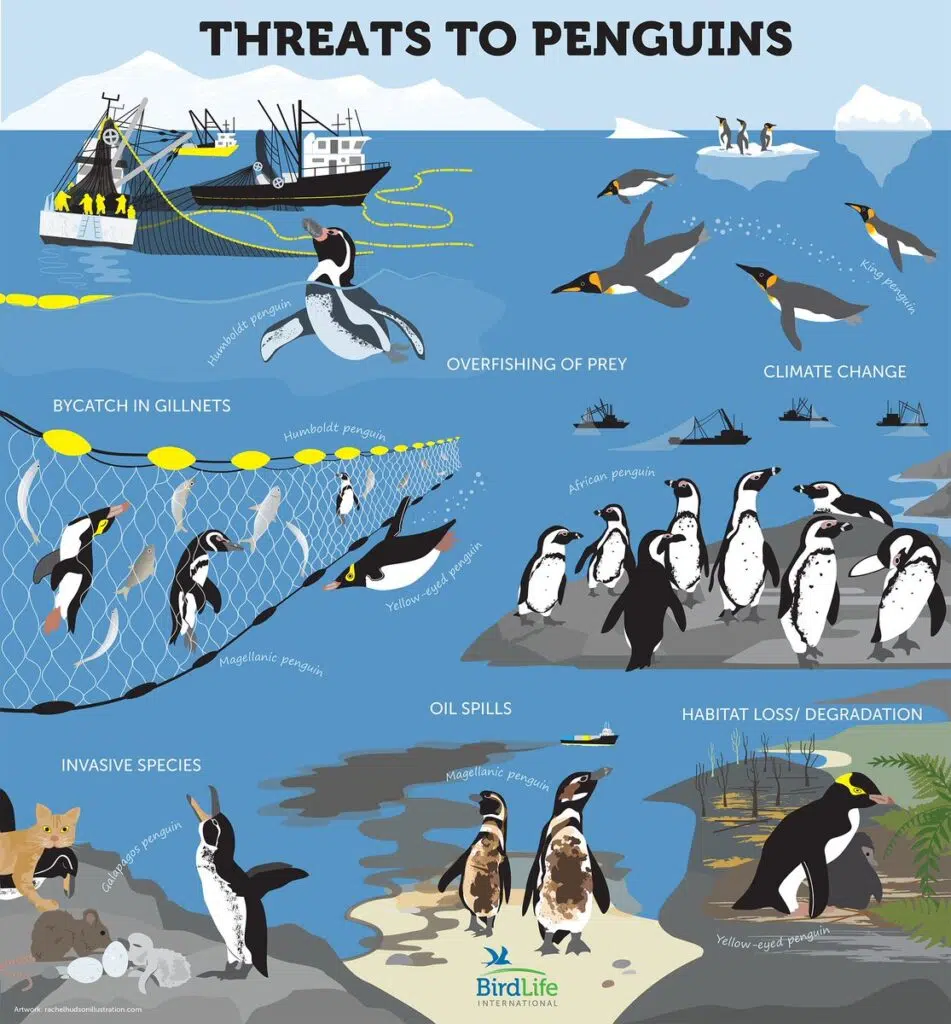

The findings are concerning given KBAs are a global network of ‘sites contributing significantly to the global persistence of biodiversity’. Although the researchers were not able to quantify the impact of development within particular KBAs, infrastructure is considered one of the greatest drivers of threat to species on the IUCN Red List. Beyond directly destroying habitat and fragmenting ecosystems, infrastructural development can drive a range of other threats, such as pollution, human disturbance and hunting, as well as the spread of invasive species.

“It’s concerning that human developments exist in the vast majority of sites that have been identified as being critical for nature,” said Ash Simkins, lead author of the study and now a Zoology PhD student at the University of Cambridge. “We recognise that infrastructure is essential to human development but it’s about building smartly. This means ideally avoiding or otherwise minimising infrastructure in the most important locations for biodiversity.”

To conduct the assessment, the team intersected maps of the world’s 15,150 terrestrial KBAs with spatial datasets of different types of infrastructure from WWF’s global intelligence platform, WWF SIGHT . They found that most KBAs contained multiple types of infrastructure, with roads by far the most common, present in a staggering 75% of these globally important sites for nature. This was followed by powerlines and urban areas, both present in 37% of KBAs.

A growing issue

As society ultimately depends on infrastructure, the team then set out to explore the potential impact of future development. Although this information was only available for mines, oil and gas infrastructure and powerplants, it still makes for concerning reading. For instance, proposed concessions and development plans suggest that an additional 2,201 KBAs could contain mines – an increase of nearly 300% – while a further 1,508 may contain oil and gas infrastructure, and another 1,372 may contain powerplants in the future.

To make matters worse, much of this future development is likely to take place in some of the world’s most biodiversity-rich regions, with countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America and parts of South-East Asia amongst the areas with the highest proportion of extractive claims, concessions or planned development in their KBA networks. In certain countries, such as Serbia, Bangladesh and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – which is home to more than 1,000 bird species – infrastructural development is earmarked in all of their known KBAs.

“Infrastructure underpins our societies, delivering the water we drink, the roads we travel on, and the electricity that powers livelihoods,” said Wendy Elliott, a co-author of the paper and Deputy Leader for Wildlife at WWF. “This study illustrates the crucial importance of ensuring smart infrastructure development that provides social and economic value for all, whilst ensuring positive outcomes for nature. Making this happen will be the challenge of our time, but with the right planning, design and commitment it is well within the realms of possibility.”

A sector where these issues may become increasingly prominent is the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy resources. While undoubtedly essential to averting the catastrophic consequences of the unfolding climate crisis, renewable technologies often require mining for precious metals, and poorly placed facilities can have significant impacts on wildlife. Given that the biodiversity and climate crises are two sides of the same coin, and need to be tackled in tandem, its vital that this transition doesn’t jeopardise conservation efforts.

“We need smart solutions to the climate crisis whilst avoiding or minimising negative impacts on biodiversity,” said Simkins. Fortunately, a growing number of tools, such as BirdLife’s Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool and AVISTEP (The Avian Sensitivity Tool for Energy Planning), are equipping key decision-makers with the information to do this. At this critical juncture for both the climate and biodiversity, its essential that the impact projects will have on nature are at the forefront of decisions.

“At the UN biodiversity COP15 meetings in Montreal last year, governments committed to halting human-induced extinctions,” said co-author Dr Stuart Butchart, Chief Scientist at BirdLife International. “Widespread destruction or degradation of the natural habitats within KBAs could lead to wholesale extinctions, so existing infrastructure in KBAs must be managed to minimise impacts, and further development in these sites has to be avoided as far as possible.”

‘A global assessment of the prevalence of current and potential future infrastructure in Key Biodiversity Areas‘ was published in Biological Conservation. Find out more about BirdLife’s Science here.

By Liam Hughes

Header Image: New satellite data have revealed the full extent of the impact of forest loss, and in many regions it is worse than previously thought © Richard Whitcombe/Shutterstock

Famed for their rich diversity, the unique trove of the millions of species inhabiting tropical forests has inspired numerous stories, accounts and ambitious expeditions throughout history. More recently, the value of this habitat in storing immense quantities of carbon has pivoted it into the spotlight as a critical tool in our fight against climate change.

However, as the human footprint continues to carve into natural areas to meet our seemingly insatiable, and unsustainable, demand for resources, habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation have emerged as the main threats to tropical ecosystems worldwide.

While forest loss has long been recognised as a critical threat to the world’s forest-dependent birds, it is only with the relatively recent advent of accurate remote sensing data, which are based on satellite imagery, that the realities of its impact can be quantified. A collaboration with the World Resources Institute, which runs Global Forest Watch, has enabled BirdLife’s Red List team to reassess how much forest loss has occurred within the ranges of thousands of forest-dependent bird species over the last 20 years.

Although already recognised as a critical threat across the world’s tropical forests, in some regions the scale of devastation has been even worse than scientists had feared. The impact of the accelerating loss of this iconic habitat has seen a flurry of species move to a higher extinction risk category in IUCN’s 2022 Red List update for birds.

TROUBLE IN SUNDALAND

One of the greatest causes for concern is in South-East Asia, a region that has seen some of the highest rates of forest loss globally over the last 50 years. The data are particularly bleak in Sundaland, an area comprising the Thai-Malay Peninsula and the islands of Borneo, Sumatra and Java. Home to some of the world’s oldest and most biodiverse rainforests, precipitous rates of forest loss across this area have sent some of the world’s most iconic and unique species accelerating towards extinction.

Species in the tropics tend to separate themselves by altitude, with montane and lowland forests often hosting different suites of species. In Sundaland, lowland species are under critical threat, as increasingly accessible tracts of flat, low-lying forest become prime targets for

conversion to plantations and infrastructure projects. The widely publicised clearance of tropical forests for oil palm plantations is a particular issue in Sundaland, and while much focus has been towards its impacts on emblematic mammals such as Orang-utans and Asian Elephants, it is also devastating numerous bird populations, as highlighted in the latest Red List update.

For instance, Malay Crestless Fireback – a pheasant species that once occurred widely across Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra – was re-evaluated from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered. Between 2001-2021, satellite data indicated that almost 70% of the forests on which it depends had been cleared, and even in those that remain, there is evidence of hunting, including in ostensibly protected areas, which could compound losses.

This devastating pattern is mirrored on the island of Borneo, a renowned biodiversity hotspot with high concentrations of endemic and restricted range species. As with its mainland cousin, Bornean Crestless Fireback was also uplisted to a higher threat category, this time to Endangered, while 2022 also saw the impressive Bornean Ground Cuckoo and enigmatic Bornean Bristlehead – a species so unique it is the sole member of its family – debut as species threatened with extinction; both are now assessed as Vulnerable.

MORE THAN JUST HABITAT LOSS

Central America is another of the world’s biodiversity hotspots where satellite data have revealed forest loss to be even worse than feared. The region has undergone several periods of deforestation, dating back to ancient Mayan civilisations, before European colonisation saw a

proliferation of plantations during the 19th century. Over the last 50 years there has been an increasing rate of deforestation to clear land for cash crops and cattle production for European and North American markets. Forest loss has accelerated substantially since 2015, particularly outside of protected areas, and there are now just five large, intact forests remaining in Central America.

This devastating loss of habitat is a major cause for concern, and has resulted in White-throated Shrike-tanager, a species predominantly found deep within lowland forests, to be flagged for conservation attention for the first time. However, as patches of forest become smaller and more isolated, often accompanied by a proliferation of logging roads, deforestation also tends to exacerbate other threats to species.

Hunting pressure, whether for food or to supply the lucrative pet trade, is one of these, as once remote forests become progressively more accessible. In Central America, the devastating combination of forest loss and hunting has seen the uplisting of three bird species previously considered Least Concern: Slaty-breasted Tinamou (to Vulnerable), and Tawny-faced Quail and Black-eared Wood-quail (both to Near Threatened).

A TALE OF TWO APALISES

Although deforestation in the Americas and South-East Asia often dominates headlines, it has also taken its toll in Africa. Here, its drivers are as complex as the continent is vast, ranging from policies focused on increasing revenue from extractive industries and food production at the expense of forest to the impacts of natural disasters and a lack of alternatives to forest resources for heating and cooking in rural areas. In the most recent Red List update, changes made to the statuses of two apalis species – small, long-tailed warbler-like insectivores – reflect the impacts on birds.

Sharpe’s Apalis occurs across the lowlands of the Upper Guinea forests of West Africa, a once vast tract of forest. Unfortunately, recent remote sensing data report 22% of forest cover loss within this species’ range over the last decade alone, leading to a Near Threatened assessment. This is much faster than previously recorded, despite deforestation affecting this region for more than a century. The major drivers of deforestation here are unregulated logging and slash-and-burn agriculture, all magnified by an increasing human population, but significant areas have also been lost to mining activities and large-scale agriculture for other key global commodities such as rubber, cocoa and oil palm.

While the loss of West Africa’s rainforests is undoubtedly a tragedy, the issue is well known within the conservation community. Valiant efforts are ongoing from several conservation organisations, including BirdLife partners, to ensure that key areas of the range of Sharpe’s Apalis are safeguarded in the future, and these continue to provide hope that forest loss won’t drive the species to extinction.

The long-term outlook for the closely related Chirinda Apalis, recently assessed as Vulnerable to extinction, is even bleaker. Found on the opposite side of Africa in the highlands along the border of Zimbabwe and Mozambique, the rate of forest loss in this area has historically been poorly documented. However, emerging data highlight its severity, with over a third of the region’s forest cover being lost in the last decade alone.

This is largely driven by a lack of sustainable livelihood opportunities for local communities, which has led to the extensive exploitation of forests for charcoal production and shifting agriculture. The tragic impacts of 2019’s Cyclone Idai, which is estimated to have killed more than 1,500 people and displaced 400,000 in the region, has accelerated this exploitation against a background of human suffering.

“This rate of forest loss is clearly not sustainable,” warns Rob Martin, Senior Red List Officer for BirdLife. “However, there are no signs of it stopping any time soon and, unlike its West African counterpart, it is not clear that any of Chiranda Apalis’s range is adequately protected.”

PROTECT TO SURVIVE

These changes to the IUCN Red List reflect the urgency of protecting tropical forests and the need to end, and ultimately reverse, deforestation. This endeavour is a core pillar of the BirdLife partnership, which works closely with local communities around the world to safeguard these iconic ecosystems. Over the last decade, BirdLife and its partners have established and upgraded several large forest protected areas, including Greater Gola in Sierra Leone and Liberia, Madagascar’s Tsitongambarika and Siem Pang in Cambodia.

To scale up the protection and restoration of forests, BirdLife has also joined forces with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and WWF since 2016 to form Trillion Trees, a partnership that has since helped protect and restore over 83 million ha of forest across the world. Stemming from this is BirdLife’s ‘Forest Accelerator’, an ambitious attempt to break away from traditional funding models and move towards finding innovative and sustainable conservation finance solutions, allowing local communities around the world to benefit from protecting and restoring forests.

For instance, in the Atlantic Forest of South America, which has had some of the world’s highest deforestation rates, BirdLife partners Guyra Paraguay and Aves Argentinas are helping communities to cultivate yerba mate under the forest canopy, thus keeping forests intact. Meanwhile in Cambodia’s Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary – home to an astonishing six Critically Endangered bird species, including the newly uplisted Masked Finfoot – BirdLife partner NatureLife Cambodia is building on a successful ‘Ibis Rice’ scheme to develop a programme that will implement several community-based projects to avoid deforestation, in turn producing carbon credits to fund conservation.

Even in protected areas, hunting and forest degradation continue to threaten many species, to the extent that it is vital that robust enforcement measures are put in place. Across the world, BirdLife partners are aiding this, including the RSPB (BirdLife in the UK), which is training community members as rangers in Sierra Leone, and the Haribon Foundation (BirdLife Philippines), which is working closely with the indigenous Bantay Gubat (‘Forest Guards’) to monitor and report illegal activities across several of the country’s forests.

These are just a few examples of projects undertaken by BirdLife’s Forest Programme. While undoubtedly essential in joint efforts to tackle both the biodiversity and climate crises, the widespread impacts of accelerating forest loss, so starkly highlighted in 2022’s Red List update, points to the urgency of drastically scaling up such projects, including the need for government involvement.

Lula da Silva’s win over Jair Bolsonaro in the Brazilian presidential election in late 2022, and his immediate pledge to end deforestation in the Amazon, offered some much-needed hope for the natural world. It is now vital that leaders in other tropical regions commit to – and importantly act on – similarly ambitious goals, and that those in developed nations, whose interminable demand drives so much of this devastation, pledge to support these efforts wholeheartedly.

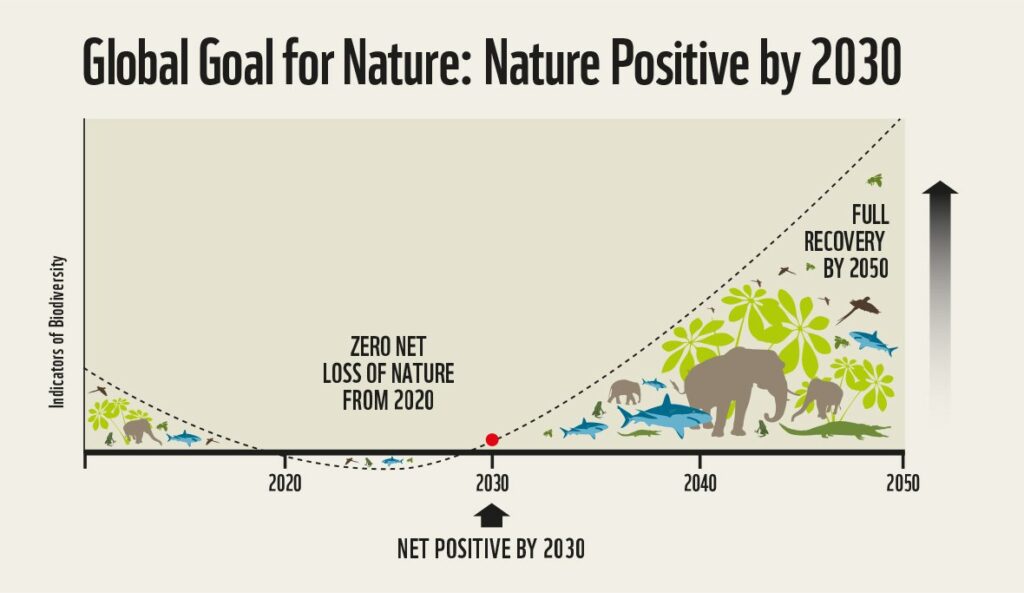

Today we’ve heard again from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change is here and must not be ignored any longer. The IPCC has repeatedly told us that nature and people are being impacted by climate change through increasing extreme weather events, sea level rise and global warming. The window for acting is closing, with the risk of overshooting the 1.5°C target high and the recent reports making clear that there are now irreversible changes to our world’s ecosystems and nearly half the global population is living in the danger zone of climate impacts.

The latest Report will directly inform the Global Stocktake happening at COP28 in the United Arab Emirates where the world will determine global progress in line with the Paris Agreement goals. Now is the time to push our global leaders across governments, business, industry and communities to increase ambition and deliver the changes needed. The IPCC has clearly set out the issues and what must be done, and BirdLife is in a unique position to help deliver solutions.

Header image: © OSORIOartist / Shutterstock

One of the fundamental takeaways from this report is that climate change and biodiversity loss are deeply intertwined. Not only is climate change pushing many species and ecosystems to the brink, but biodiversity loss is accelerating climate change. The science has shown that limiting warming to 1.5°C will not be possible without protecting and restoring nature. Emissions from agriculture, forest loss and other land use changes represent almost a quarter of total global emissions. To get keep our climate within safe limits and build a resilient future, we must tackle unsustainable land use and deforestation, protect and restore nature, and support our ecosystems to adapt and thrive.

BirdLife’s unique global to local approach is helping to deliver climate action around the world. BirdLife is working with the BirdLife Partnership to push governments to link their biodiversity and climate agendas through advocating for increased ambition at the global Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and UNFCCC COPs. We are working to deliver projects including reforestation in South America, coastal saltmarsh creation in the United Kingdom, supporting nature-safe renewable energy developments across Africa to Europe, and launching our innovative flyways initiatives in partnership with the Asian Development Bank and the Latin American Development Bank.

But we can all do so much more.

Support BirdLife’s advocacy work to make leaders listen to the science, and put in place the vital policies and investments to ensure nature is at the heart of solving the climate crisis.

You can support BirdLife today by:

- Supporting your local BirdLife Partner in holding governments accountable to their climate promises and forcing greater national ambition.

- Join BirdLife International as a member and support our international advocacy work negotiating for nature at the Climate COPs.

- Make a donation. Combatting global challenges like the climate crisis requires vast resources, everything you give gets us one step closer to saving people and nature from these impending catastrophes.

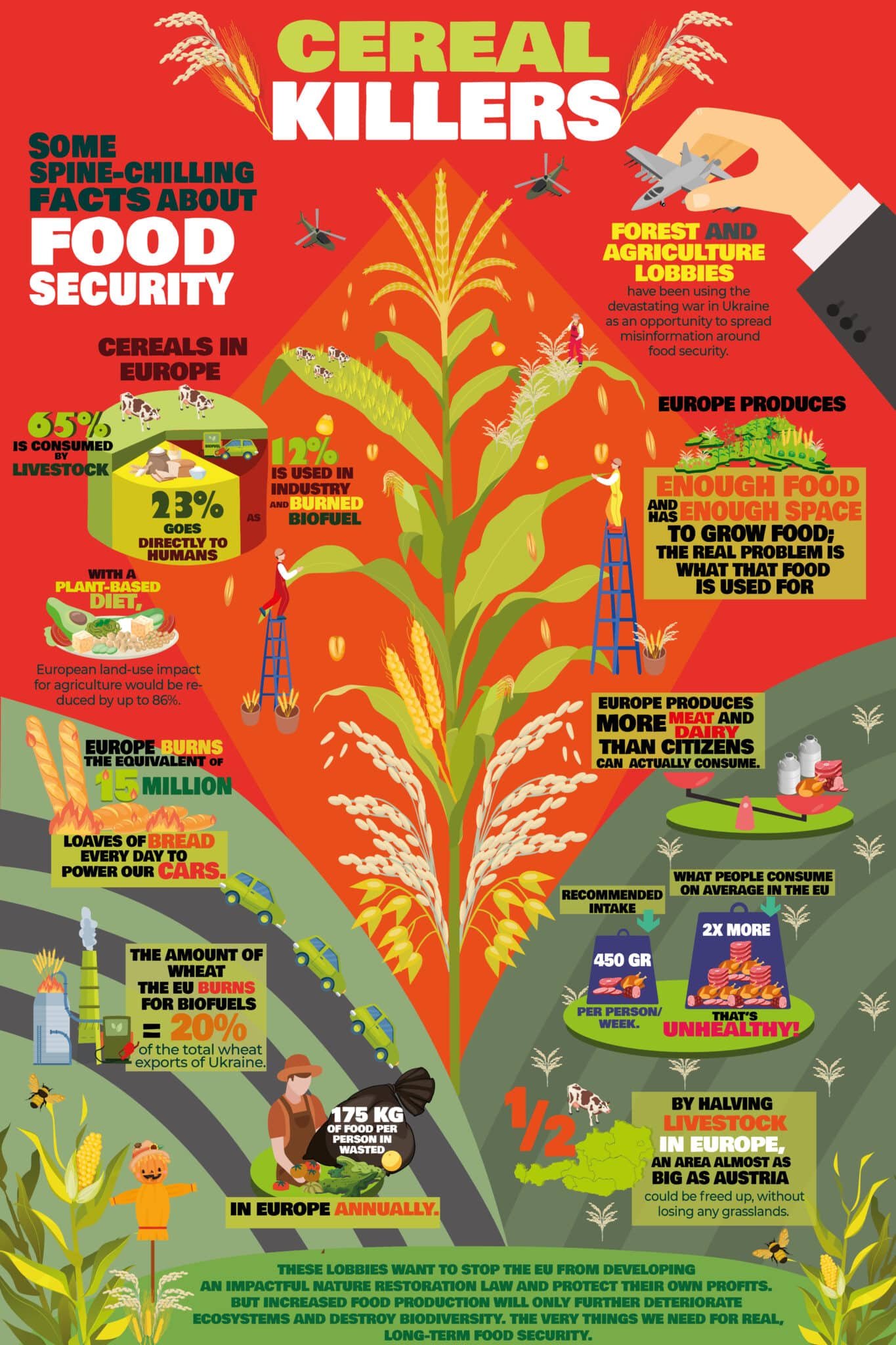

The EU burns the equivalent of 15 million loaves of bread a day. Yes, you read it correctly: a day. So, instead of breaking out in cold sweat because you think we are in a food security crisis, think about these facts and what is actually done with the food available in Europe. Instead of burning 20% of Ukraine’s wheat supply, these cereals can be exported to countries that face real food security issues in the Middle East and North Africa.

Over 2/3 of cereals in Europe goes to feeding livestock. Have you ever thought about how inefficient it is to feed plants to livestock rather than to eat them directly? Demand drives consumption. Reducing your meat consumption can already make an impact! Of course, EU and national food strategies should contain laws and regulations that steer our consumption decisions in favor of sustainability and health. If we would consume less meat – and stop burning crops for biofuel in the EU – we would save lots of land without compromising the traditional landscapes we have.

Why do we need to restore nature?

Because we depend on it. For our very survival. Restoring peatlands and floodplains, forests and grasslands significantly reduce the risk of catastrophes such as floods, fires and droughts that can wipe out food production in entire regions, sometimes overnight.

If we want real long-term food security, we need to stop the rapid decline of biodiversity and restore our relationship with nature today, not tomorrow. It is time to get our priorities right and listen to science. Because who can imagine a world without bees and other pollinators? We certainly can’t.

By Caroline Herman

References

Buckwell, A. and Nadeu, E. 2018. What is the Safe Operating Space for EU Livestock? RISE Foundation, Brussels.

European Parliament. Food waste: the problem in the EU in numbers (2017, May 15). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20170505STO73528/food-waste-the-problem-in-the-eu-in-numbers-infographicEurostat 2018/2019

Friends of the Earth & Heinrich Böll Stiftungt, Meat Atlas 2021, https://friendsoftheearth.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MeatAtlas2021_final_web.pdf

Greenpeace EU. (2020). False sense of security: Why European food systems lack resilience. https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-eu-unit-stateless/2020/10/85cc908b-false-sense-of-security_final_en.pdf

Kustar, Anna & Patiño-Echeverri, Dalia. (2021). A Review of Environmental Life Cycle Assessments of Diets: Plant-Based Solutions Are Truly Sustainable, Even in the Form of Fast Foods. Sustainability. 13. 9926. 10.3390/su13179926.

Ruiz Mirazo, J., WWF European Policy Office. (2022). Europe eats the world. In https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/europe_eats_the_world_report_ws.pdf.

Transport & Environment. Food not fuel: Why biofuels are a risk to food security. (2022, September 30). https://www.transportenvironment.org/discover/food-not-fuel-why-biofuels-are-a-risk-to-food-security/

You might also be interested in:

| Stichting BirdLife Europe gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Commission. All content and opinions expressed on these pages are solely those of Stichting BirdLife Europe. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. |

Usually when you pay for drinking water, you are paying a water company for its services: filtration, sanitation, maintenance of supply, staff overheads and more. But what if that company was nature itself? Is it possible for a forested landscape to be recognised for the freshwater service it provides, filtering rainwater down through the soil, releasing a clean, steady flow? Can the local people living there be rewarded for protecting this forest? In the Mbeliling landscape on Flores Island, Indonesia, the answer is a resounding yes.

Nature provides a multitude of benefits for our survival and wellbeing but is often taken for granted. However, the work of Burung Indonesia (BirdLife Partner) in Mbeliling is proving that innovative schemes such as Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) are a great way to ensure recognition of nature’s direct value and help keep forests standing. It’s also tackling one of conservation’s biggest challenges: how to break free from unsustainable funding models and tap into the huge scale of the private sector. Get it right and, like clean water from a spring, the potential flow of support is huge.

A patchwork landscape

Mbeliling consists mainly of locally managed protected forests and production forests, including mixed smallholder agroforestry systems, rice-crops and animal husbandry. It is a stunning patchwork of smallholdings and tropical rainforest, crucial habitat for threatened birds such as Flores Monarch (Endangered) and Flores Hanging-parrot (Vulnerable). As a key catchment area, the landscape supplies fresh water to 36 villages and the district capital, Labuan Bajo, which is increasingly becoming a popular tourist destination.

The trouble is, the growth of the tourism sector in recent years has led to conversion of agroforestry farms to tourist facilities, reducing the water absorption and retention capacity of the landscape. As a result, Labuan Bajo is facing water scarcity and the cost of water has increased for residents. Moreover, the local income opportunities of tourism are not shared equally. A more sustainable solution is needed to meet the needs of the people, increase the vegetation cover of the natural landscape and conserve its threatened species.

Selling water to fund conservation

Using seed funding from the BirdLife Accelerator, Burung identified a PES scheme as a fair cost-sharing arrangement that would solve these issues. Tiburtius Hani, Programme Manager of Burung Indonesia in Flores explains: “Payment for Ecosystem Services is a way to take collective action among upstream communities and water consumers to conserve spring water and the water catchment area within the landscape in a sustainable and equitable way.”

In 2020, Burung Indonesia established a social enterprise selling drinking water to fund conservation activities, to test the willingness to of the private sector and consumers to pay for conservation upstream. After a successful trial, 28 small water companies signed up for the Labuan Bajo Water Care Entrepreneurs Association. With support from the BirdLife Accelerator, Burung aims to formally register the Association, start collecting payments for ecosystem services from its members, and manage these funds for conservation activities transparently.

Effect on the landscape

Burung have been working in the landscape since 2007 and have built close ties with the local communities, through local conservation agreements, promoting alternative livelihoods and businesses and more. Adi Widyanto, Head of Conservation and Development at Burung has seen the impact their work has had on the landscape: “So far, our Flores Programme has managed to stabilise land-use and forest cover throughout the landscape. In particular, by 2021 about 10,000 hectares of forest area has undergone a significant natural succession from a degraded state to a mature secondary forest. Such an impact can only be achieved when forest is guarded from disturbance over a considerable time – allowing the forest to restore itself.”

The next step is to scale-up the water payment trial and now, with further support from the BirdLife Accelerator and communications training from Terranomics, Burung are pitching to larger private companies. Permata Qua, a water processing company in Labuan Bajo is on board with the scheme. “This is an important initiative that needs to be supported by all parties,” says Rius Surianto, the company’s director. “Protecting water catchment areas means maintaining business sustainability and better meeting the needs of the community.”

More support would mean they could expand the scheme onto priority farmlands in the landscape for forest restoration efforts – creating a ‘demonstration plot’.

“This innovative project gets to the heart of what the BirdLife Accelerator is about,” says Aron Marshall, Forest Programme Officer for BirdLife International. “Burung are demonstrating what can be achieved when investment is made into the small, innovative ideas that are working on the ground and scaling them up. It’s creating the kind of transformation that will allow conservation to sustainably finance itself in the future.”

Now in its third year, the BirdLife Accelerator (aka BirdLife Forest Landscape Sustainability Accelerator) has seen considerable success, from pioneering feasibility studies, to building conservation enterprises, to shipping sustainable commodities worldwide. We are building on this success through expanding our portfolio, further advancing some of the major projects from the last two phases, whilst bringing on several newcomers who have ideas with huge potential. Not only this, but with the introduction of our new forest carbon portfolio into the Accelerator, we are supporting Partners to explore the potential for the multi-million dollar carbon market in their landscapes.

- If you are interested in learning more or investing in the 2022/2023 BirdLife Accelerator cohort, please visit our website: www.birdlife.org/projects/forest-accelerator-investing-forest-conservation or email: [email protected].

Trillion Trees

Trillion Trees is a joint venture between BirdLife International, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and WWF to urgently speed up and scale up the positive power of forests. Our work helps protect and restore forests all over the world for the benefit of people, nature and climate. To learn more about how we’re improving forest protection, advancing restoration and ending deforestation visit trilliontrees.org and follow us on Twitter @1TrillionTrees.

I grew up in Nairobi reading about the forest and its power, but I never fully appreciated it until one of my relatives, who works in natural conservation, inspired me to want to work in landscapes. I was also inspired by Wangari Maathai. She was a woman who defended what she believed in and left a legacy. Conservation work is still mostly done by men, so women need to carve a path.

Studying natural resource management at Egerton university, I found environmental issues very interesting and often thought about the impact I could have. In 2014, I started working for Nature Kenya, and am now a Project Officer. Since then, I have really grown as a conservationist and can thank Nature Kenya for shaping me into the person I am today in my conservation journey.

My first main job was working with women in the Tana Delta to help build nature-based enterprises to improve livelihoods. Women were often not considered, so this gave me the chance to make a difference and also the opportunity to work in a remote area for the first time; so it was a real eye-opener for me. I learned to engage and work with the community, seeing first-hand how to build consensus, and how to engage a network of stakeholders at county, local, national and international levels.

This article is part of a narrative series from global conservationists working as part of Trillion Trees.

In many landscapes in Kenya, women are the champions. Even older women get involved in conservation. We need to engage them further.

As part of my role, I have been trained in tree-planting and natural habitat monitoring, so I’m confident I can go to any area and assess the immediate threats, the state of the habitat, the rivers and rain. I can also identify birds and understand them as indicators of the health of ecosystems. And, I’m able to train the community in these skills and help them understand how they can help preserve their surrounding habitat.

My days are incredibly varied and interesting. I work in three counties – Embu, Meru and Tharaka Nithi – and will often visit all three in a typical week. I might start the week in Meru, training the community in beekeeping, for example, including hive monitoring and management, bee products harvesting, packaging and marketing. Later in the week, I might go on a site visit in Embu, visiting the various restoration areas and recording what I see on a specially designed app. I’ll check for threats, look at the survival count for the seedlings, walk around and see how the saplings are doing, and then write a report that forms the basis of the next plan. Various other stakeholders also come into play throughout the days, such as local governments.

Our restoration activities change according to the seasons. The planting season coincides with the rains, which are different depending on the area: In Meru, it’s October to December, and in Embu, it’s March to May. When we are not planting, we focus on community capacity building and habitat monitoring.

Two aspects of my work in particular give me huge satisfaction and are closely linked and cut across all the projects we implement. The first, which I love, is interaction with the community, including capacity building, support for their activities and conflict resolution. Forest restoration and conservation come as a close second, and they are dependant on the first; you need to build the capacity of the community to be able to carry out the restoration. The community becomes your watch-guard.

The focus and method of our work depend on the area, the tree species therein and the climate. In Mt Kenya, one of the main aims is water catchment restoration. We want to build the capacity of the water providers and support them in nature-based enterprises, so we are aiming to connect the water buyers and the water users with community groups that are carrying out the conservation.

Stakeholder relationships are key. We have strong links with the Kenya Forest Service and with the county governments that oversee forests and provide valuable technical input. And we need to maintain a good working relationship with the policymakers.

One of the biggest challenges we face is variation in rainfall patterns. Two to three weeks of rain are needed for the saplings to survive, and many of them can be lost if the rains don’t come. Grazers are also a threat and can sometimes eat the saplings, but communities have come up with ways to put up protective fencing against this. We have also identified tree species that are unpalatable to the local wildlife so are less likely to be eaten.

Climate change is affecting the rainfall with many areas already much drier than they used to be. This affects the tree species that we can plant and the way we plant. For example, the local communities used to collect ‘wildings’ from the forest to cultivate, but there are no longer enough to be found. One glimpse of hope is that we are working on species diversification to try to find those that are more drought resistant and can cope better with climate change.

One of the most satisfying parts of my work is seeing how all our efforts pay off and the difference we can make in restoring an area of forest. In one particular area, the forest has been transformed over a few years from a landscape choked by a very fast-growing plant called Lantana camara, to a vibrant, thriving forest, thanks to the efforts of the community working together to clear the Lantana, manage the land and take care of the newly planted tree saplings. Local people talk about how beautiful the area is now and how even the weather has changed. They feel a strong connection with the forest having been part of the restoration effort and having made a real difference.

One of the most important lessons I have learned through my work is that this is a collective effort – everyone from young to old needs to play a part. If the community works in cohesion, with different stakeholders all working toward a common goal to conserve, restore and protect the forest and the ecosystem for future generations, we can achieve so much more.

More and more women are getting involved in conservation and are often direct beneficiaries of the projects. Women are often at the center of their communities and have enormous influence. The more women we can involve, the more we can achieve – for example, we can help them use new technologies such as biogas for energy rather than the more traditional collection of firewood. I can see the small milestones we make and the positive impact on the lives of the community, and this motivates me in my work every day. We may think we do little, but when we measure the impact and put some numbers to it, we can see that we have achieved a lot.

There are challenges working as a woman in conservation, such as balancing work and field trips with raising a family. But it is hugely rewarding. And at the heart of what I do every day is the scenic beauty of the landscape. I love being in the forest. I like the peace and ambiance I find there that I don’t find anywhere else. I believe that if we work together, we can protect these precious landscapes for future generations.

Nature Kenya is a Partner of BirdLife International, a Trillion Trees partner.

The entire BirdLife family, led by Her Imperial Highness, Princess Takamado, Honorary President, joins its UK member, the RSPB, and our friends and supporters in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth, in offering our deepest sympathies to the Royal Family on the loss of their mother, grandmother and great grandmother.

BirdLife CEO Patricia Zurita saluted the important role played by Her Majesty the Queen as patron of the RSPB and the love of nature she displayed and passed on to her children and grandchildren over the years. “We are deeply grateful for her long support to the RSPB and so many other charities over her long reign and her true commitment to nature and making the planet a better place. May she rest in peace.”

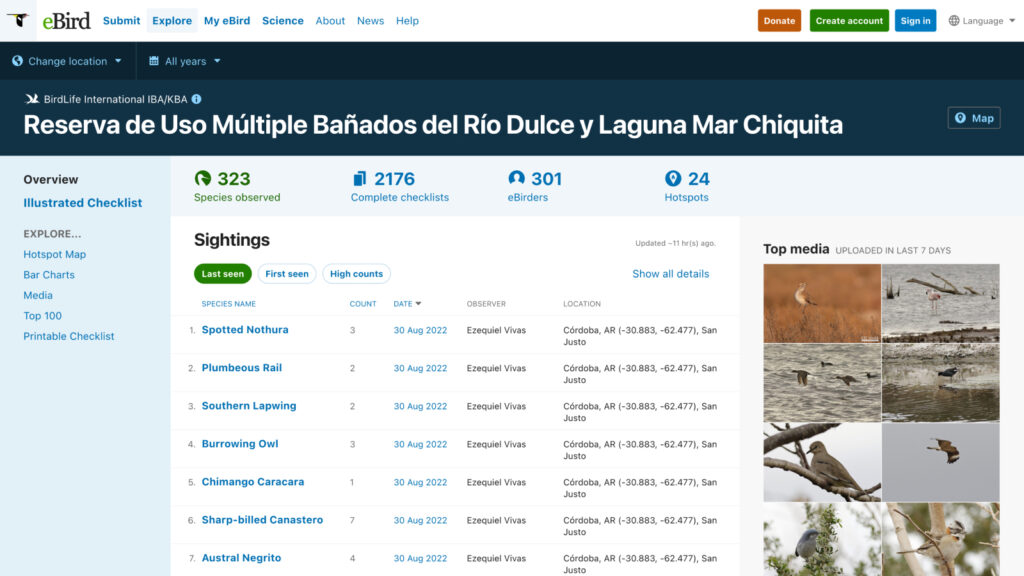

The eBird project is one of the largest citizen-science data platforms in the world – with more than one billion records. Birders worldwide use eBird for recording the species they observe, and this vast information repository contributes to our global understanding of species’ distribution, abundance, movements, and population trends. Through a new collaboration with BirdLife, eBird data will be more useful than ever to identify new key sites for nature as well as support the vital conservation efforts of BirdLife Partners.

This week, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (which manages eBird) and BirdLife launched a new tool that marries the power of eBird with the strength of BirdLife’s network of national partner organisations, as part of a collaboration to monitor and conserve the most important sites for nature. BirdLife has identified over 13,600 Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) worldwide, and these form the core of a wider network of Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) – critically important sites for the persistence of global plant and animal diversity. Data on IBAs and KBAs are now integrated into eBird, enabling BirdLife Partners to see key summaries in eBird for each of their country’s IBAs and KBAs, including the species that have been observed, by whom, when and in what numbers. Likewise, eBird users can see when their observations fall within IBAs – their personal contributions to the monitoring of these sites.

By Shaun Hurrell

Header Image: Birdwatchers © Barend Van Gemerden

Filling data gaps with the power of citizen science

Protecting and conserving sites is a vital part of international targets to save nature. One of the key commitments for the Global Biodiversity Framework (to be adopted by the world’s governments at the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s COP15 in December 2022) is to expand protected and conserved areas to cover 30% of land and seas by 2030, especially ‘areas of particular importance for biodiversity.’ KBAs are the most comprehensive, systematically identified network of such sites worldwide and will be crucial in focusing protected area expansion on the most important locations, and to achieving the targets in the framework. However, gaps in the network remain, many site assessments need updating, and all need effective monitoring.

Data provided by eBird’s more than 800,000 users can help fill these gaps. These data are also updated in real time, so accurate, current assessments can be made of the state of populations of key species in these important sites and how they change over time.

“The eBird data can be used to help pinpoint new sites that qualify as IBAs and KBAs,” said Dr Stuart Butchart, Chief Scientist at BirdLife International, “by highlighting locations outside the existing network that support globally significant populations of species of conservation concern. They can also help monitor the populations of such species in these sites over time, for example, by tracking the proportion of birders’ checklists reporting a particular species at a particular location.”

“The eBird data can be used to help pinpoint new sites that qualify as IBAs and KBAs, by highlighting locations outside the existing network that support globally significant populations of species of conservation concern.”Dr Stuart Butchart, Chief Scientist at BirdLife International

Birders play an important role

Local birders can provide vital information on species such as the timing of arrival from migration to track climate change impacts, or provide population estimates for key species to inform the effective management of a site. The growth of an international community of people supporting nature conservation is a shared goal of both the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and BirdLife. The number of people contributing bird observations to eBird grows by approximately 20% each year, thanks in part to Cornell’s Merlin Bird ID app, a bird-identification tool that utilises cutting-edge technology to help users identify the species they see and hear, and to engage people in the joy of birds.

The ever-growing dataset of observations generated by these users can be used by BirdLife Partners to identify, update, and monitor IBAs. This then can inform BirdLife’s advocacy work and highlight to governments particular sites in need of protection. Data from eBird can therefore be used to help to designate new or expanded protected areas, to recognise community-managed reserves or other conserved areas, and to ensure these are managed effectively, thereby helping governments to meet their 2030 commitments to save nature.

So next time you log an observation on eBird, you should feel proud that you’re contributing a vital data point to help us understand our world – potentially supporting the case for a new protected area, helping to ensure that existing protected areas are effectively managed, or supporting the growth of the global birding community. Thank you.

Future directions

BirdLife and Cornell are now exploring further collaborations and greater integration of their datasets, with the aim of strengthening this network of critical IBAs and KBAs and supporting bird community and conservation globally.

More information

You can explore the new tool here:

www.ebird.org/explore/birdlife

More information on IBAs:

www.birdlife.org/projects/ibas-mapping-most-important-places

Explore the global database of KBAs and find your local KBA using the map tool:

Why study the sound of bird song?

There’s a growing recognition of the benefits of spending time in nature for our health and well-being. At the same time, we’re experiencing widespread and ongoing biodiversity loss, meaning that the quality of our interactions with nature are also likely to be declining. Sound plays a key role in our experience of nature, with birds in particular providing the soundscape of time spent outdoors, so we wanted to examine how changes in bird populations are impacting the acoustic characteristics of natural soundscapes.

Header image: The Ortolan Bunting’s high-pitched, whistling song is being heard much less widely in Europe and western Asia © Simonas Minkevicius

How did you obtain the soundscapes?

We don’t have many historical recordings of natural soundscapes. Instead, we reconstructed them by combining annual bird monitoring data from over 200,000 sites across North America and Europe with sound recordings for individual species. We inserted the same number of clips for a species as there were individuals counted. So, for example, if five Skylarks were recorded at a site, we inserted five 25-second clips of Skylark song. We then layered up the sound clips for each species to build a composite soundscape for each site that represented what it would have sounded like for the observer conducting the annual bird count.

How does the modern sound of Spring differ to how it did 25 years ago?

We found that acoustic diversity and intensity have declined across both North America and Europe over the past 25 years – that is, our natural soundscapes have become quieter and less varied. We also found that sites that have experienced the greatest declines in species richness or abundance also tend to show the greatest decline in soundscape quality.

Why is it important that the soundscape of bird song is changing?

Bird song has always been a defining component of our relationship with nature, and our results suggest that one of the key pathways through which we engage with, and draw benefits from, nature is in chronic decline. There is also a risk that as our soundscapes become quieter and less diverse, we also start to overlook or care less about their further deterioration. Worryingly, we know that other animals that contribute to natural soundscapes, such as insects and amphibians, are also declining, whilst road traffic and other sources of ‘human’ noise are increasing, which suggests deteriorations are likely to be even greater than those reported. By demonstrating the implications of biodiversity loss for our day-to-day lives, we hope this study can help heighten awareness and encourage support for conservation.

“Bird population declines and species turnover are changing the acoustic properties of spring Soundscapes” is published in Nature Communications

Header image: A shepherd bringing his sheep and goats out to graze in Shebenik-Jabllanicë National Park, Albania © Olivier Langrand

Every morning in the summer months, Fatjoni wakes up early and emerges from his hillside farmhouse into the stunning scenery of the Albanian mountains. Their peaks stretch out around him, shrouded in clouds, their sloping sides dotted with stands of trees and golden pastureland. As he leads his herd of goats out of their enclosure and up the mountainside, flowers shine out from the undergrowth in flashes of yellow and purple. A snake, basking in early morning sun, slithers into the bushes at the sound of approaching hooves.

Fatjoni is part of a dying breed: a young pastoralist following the traditional practices used by his ancestors for thousands of years. Over the past three decades, traditional livestock breeding has been slowly abandoned as younger generations move to urban areas in search of more metropolitan opportunities. “Young people are not so keen to stay and work only with livestock. Whoever stays has to fight some kind of isolation as there is almost no digital connection in the mountains,” explains Mirjan Topi, Small Grants Coordinator for the Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund (CEPF) in Albania.

This has led to a vicious circle, as the sparse population makes it harder for those who remain to continue their livelihoods. “One of the reasons that alpine pastures are not grazed is the lack of water,” outlines Topi. “In the past, people made structures to collect rainwater. But as the number of shepherds has decreased, these structures are no longer maintained, and have lost their function.”

KEEPING WIDE OPEN SPACES

Herders like Fatjoni aren’t the only ones losing out in this situation. Over thousands of years of grazing, the mountains of the Balkans have developed a unique ecosystem. The highlands and pastures in particular are home to plant species found nowhere else, including the beautifully unusual Albanian Lilly, as well as rare reptiles such as Meadow Viper. These slopes are now a hotspot of biodiversity – but as increasingly large expanses of land become abandoned and overgrown, this exceptional wildlife community is dying out.

“I have seen degraded pastures in some areas where it was hard to find a single flower amid the dense grass,” Topi says. “It would be very hard for reptiles to live in these habitats, as it would be difficult for them to move and hunt.”

This is where BirdLife stepped in. In our role as Regional Implementation Team for the Mediterranean Hotspot, we facilitated three grants from CEPF to support traditional livestock breeding through local organisations – part of a conservation focus on ‘cultural landscapes’. AlbNatura, a local conservation group, jumped into action to improve water facilities and provide solar panels and internet antennas, enabling shepherds (including Fatjoni) to connect with the outside world. Local people are already reaping the benefits: one shepherding family is now able to keep in touch with their daughter, who studies in France.

Another grant aims to set up ecotourism in the area, helping local people to provide accommodation and food for tourists. As well as diversifying their incomes, Topi hopes that this will motivate younger generations to stay in the countryside and combine ecotourism with traditional practices. “It would be very boring for a young person to just be a shepherd, but if they got involved in tourism activities – welcoming guests into their homes, and so on – then it will be more attractive,” he reasons.

Topi recounts a touching moment when a local farmer told him:

“Thank you very much.. For 30 years no one has remembered us or provided us with help. My heart is full now to see my herd drinking water on the grazing site. It is good that things are starting to change.”

LIFELINE FOR VULTURES

A similar project is underway in Morocco, with an additional benefit: it could help bring threatened vultures back from the brink of extinction. Jbel Moussa is located near the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow strip of water that separates Africa and Europe. Vast concentrations of migratory raptors, which dislike flying over large stretches of ocean, get funnelled over this crossing on their arduous journey between European breeding grounds and African wintering grounds. Many of these birds stop to rest and refuel on the mountain slopes of Jbel Moussa, feasting on partridges, quails and small mammals that range across the open meadows – or, in the case of vultures, on the remains of dead livestock.

However, as livestock herders retreat, these wide open spaces are becoming choked with vegetation, making it hard for birds of prey such as Black Kite to hunt for food – and depriving vultures of much needed carrion. Threatened species such as Rüppell’s Vulture (Critically Endangered) and Egyptian Vulture (Endangered) are now facing food shortages at a vital stage of their journey.

To combat this, GREPOM (BirdLife in Morocco), working alongside the Department of Water and Forests, is building partnerships with local herders to collect carcasses and slaughterhouse waste, which are deposited across key areas at peak migration times. They are also encouraging pastoralists to stay in the area by providing water troughs and helping them to obtain improved accreditation and certification for their products. Herders can now get a much better deal for produce such as meat, milk, cheese and wool thanks to these premium labels. To top it off, GREPOM is helping local residents to develop birdwatching ecotourism, taking advantage of the spectacular bird migration that passes overhead at this key ‘bottleneck’.

EMPOWERING RURAL WOMEN

When we think of shepherds, we often think of bearded men in sheepskin coats carrying long wooden crooks. But a lot of shepherds in the Kroumirie region of Tunisia are women, who are often left behind to care for their flocks while the men head to towns and cities in search of work. In this case, overgrazing is the problem, since large groups of women often take their sheep into the forests around El Feija National Park. With a new management plan in place for the park, bringing with it changes to grazing practices, local conservation organisation Association Sidi Bouzitoun is promoting alternative sources of income to supplement pastoralism.

As part of this, the association provides training sessions in other traditional practices such as making honey, essential oils and pottery. They offered women from 30 families the opportunity to organise three local markets in Jendouba city to sell their wares directly, facilitated trading agreements with local shops and established a small production workshop for women in El Feija to create a new brand for essential oils.

Jason Deschamps, Project Assistant for CEPF in North Africa, explains: “The project aims to reinforce women against ‘economic middlemen’ who often abuse their positions by creating monopolies on their products, pressing unfair prices on the women who have no other alternatives.” Today, women have the confidence to attend markets in person, proudly promoting the products of their hard work and expertise. “Seeing the impact of our work on women’s lives gives me the feeling that I am in the right direction to achieve my greater goal,” says Hajer Ghazouani, Project Co-ordinator at Association Sidi Bouzitoun.

“Seeing the impact of our work on women’s lives gives me the feeling that I am in the right direction to achieve my greater goal,”

Hajer Ghazouani, Project Co-ordinator at Association Sidi Bouzitoun.

It’s a lesson that has proven itself true again and again: local people are the key to protecting natural habitats. By empowering them to manage their local ecosystems and enrich their own livelihoods, we are sowing a seed that will continue to bear fruit for many years. As Mirjan Topi says of the mountains of Albania, “These grants may be small and with a short life, but their impact and sustainability will most likely be for decades.”

Aiding Ailing Olive Groves

Jordan’s ancient olive groves – and natural forests – are under threat from urban expansion and large-scale tourism resorts. Olive yields themselves are dropping due to genetically ‘improved’ tree varieties and artificial pesticides, which also harm local wildlife. To keep trees standing and local people in profit, CEPF funded local company Enviromatics to train farmers in eco-friendly pest control and traditional practices. One farmer, who lost a whole year’s yield to insects, now knows how to save it by acquiring just a few insect traps. Another farmer thanked the project team for saving his life: while walking on his farm, he noticed the venomous Palestine Viper hidden between two trees. Without training, he might have died from a viper bite.

Image: Some trees in Jordan’s olive groves are hundreds of years old © Enviromatics

Home on the range

Morocco’s traditional rangelands protect wildlife and people from flooding and soil erosion, as well as replenishing underground water supplies. Sadly, intensive agriculture and overgrazing are depleting vegetation, causing widespread desertification. To address this, CEPF supported local organisation AFMI to revive the ancient Agdal system in Ifrane National Park. This is a communal governance system by which pastoralists manage common land and regulate the grazing of livestock. In years gone by, Agdals ensured that resources were not exhausted, and that the area’s wild plants and animals remained intact. AFMI held numerous meetings with local communities over six months, and after witnessing the growth of plants and the enrichment of wildlife, they pledged in favour of adopting this new, yet traditional, system.

Image: AFMI worked with local people to map out land use in Ifrane National Park © Zaid Salmad / AFMI

*The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, and the World Bank. Additional funding has been provided by the MAVA Foundation. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation.

CEPF is more than just a funding provider. A dedicated Regional Implementation Team (RIT) (expert officers on the ground) guide funding to the most important areas and to even the smallest of organisations; building civil society capacities, improving conservation outcomes, strengthening networks and sharing best practices. In the Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot, the RIT is entrusted to BirdLife International and its Partners: LPO (BirdLife France), DOPPS (BirdLife Slovenia) and BPSSS (BirdLife Serbia).Find out more at www.birdlife.org/cepf-med

The Negros Fruit-dove is, like its close relatives of the genus Ptilinopus, a beautiful bird, with vivid green plumage marked with bright yellow on the wing and belly, and a wide, yellow ring around the eye. Or should we say ‘was’ a beautiful bird – could it be extinct? Since its discovery, it has proved even more deserving of its scientific name arcanus, meaning secret or hidden, than its (evidently surprised) discoverers realised. The first and only record came from the forests of the Philippine island of Negros in 1953. Ornithological exploration of the island had begun long before and has continued since, yet this remains the only report.

There are grounds to think it is not extinct: a reasonable area of forest survives on Negros, with more on the nearby island of Panay, which holds almost all the same species, and there have been reports from local people of birds fitting its description. Could the lack of records be because it represents an ‘aberrant’ or unusual-looking individual of another species? But no other species comes close to a likeness, allowing for any known form of aberration. And so it remains on the Red List, as Critically Endangered: mysterious but not Extinct.

It turns out that dozens of other bird species (not to mention other animals and plants) are in a similar state: ‘lost’ but not presumed Extinct. Such knowledge gaps beg to be filled, and can inspire fieldworkers who may relish the chance to get out and look for them, often in the biologically richest parts of the planet, and potentially make other discoveries too. As the biodiversity and extinction crises worsen, uncertainties like this can cloud our understanding of the situation, and make it harder to set the right conservation priorities.

This is why a new global search effort is calling on researchers, conservationists and the global birdwatching community to mount the Search for Lost Birds, through a collaboration between BirdLife International (through our Preventing Extinctions Programme), American Bird Conservancy (BirdLife in the US) and Re:wild, with data support from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and its eBird Platform.

For the purposes of this initiative, ‘lost’ species are those with no documented sighting in the wild for at least 10 years and that are not classified as Extinct on the Red List. There are around 50 such species. Some, like the Negros Fruit-dove, have been lost much longer than this, but as the recent rediscovery of the Black-browed Babbler in Borneo 172 years after the only previous record shows, this need not mean it is too late. Others have been seen in the 21st century, but with a worrying lack of recent information. Someone needs to find them again, and keep the populations under observation, taking action to prevent them slipping away.

Alongside Black-browed Babbler, we can take heart from the story of Madagascar Pochard. After its rediscovery by the Peregrine Fund in 2006, its population was studied and monitored, the site and its surroundings (found to support an outstanding community of threatened and endemic wildlife) legally protected, and a reintroduced population was established and is now breeding elsewhere within its historical range.

Here, we outline a top 10 list of lost birds to seek out, spanning all regions, across the tree of (bird) life, from a delicate hummingbird to a raptor. Negros Fruit-dove is one. Here are the other nine:

By Roger Safford

Header image: Photo of the possibly lost Jerdons Courser © Simon_Cook

Cuban Kite

This specialist feeder on snails and slugs used to be widespread in Cuba. Habitat destruction and alteration caused by logging and agricultural conversion has reduced its range to a tiny area in the east of the island, where it is believed to be on the verge of extinction. Farmers have persecuted the species in the mistaken belief that it preys on poultry, and harvesting has apparently reduced numbers of tree snails and thereby food availability. In the last 40 years, kites have been seen in tiny numbers of a handful of occasions, mostly recently two flying birds in Alejandro de Humboldt National Park in May 2010.

Santa Marta Sabrewing

Once considered fairly common within its small range, Santa Marta Sabrewing lives in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, in north-east Colombia. It is the rarest and most threatened of the 22 bird species restricted to this Endemic Bird Area. It may migrate seasonally from the forest borders at 1,200-1,800 metres to the open páramo, reaching the snowline at 4,800 metres. Since 1946, this beautiful hummingbird has only been recorded with certainty on one occasion, a single bird humanely mist-netted in the El Dorado Reserve in 2010, despite regular visits by birders before and since. It could still be present given habitat remains, but any surviving population is certain to be small and declining as the forests and especially open paramo vegetation above the treeline continue to be destroyed, fragmented and degraded.

Vilcabmaba Brush-Finch

Vilcabamba Brush-finch has a tiny range in the Vilcabamba Cordillera of the Peruvian Andes. It may prove that the surviving populations prove to be stable and secure, but no records have been documented since 1968 in this very remote area. It occurs in montane evergreen forest, probably at 1,700-2,250 metres, where there is a high (but irregular and broken) canopy and dense undergrowth, and it has been projected that it could become very threatened in a short space of time if human pressures increase.

Priogine’s Nightjar

Prigogine’s Nightjar was described and named 35 years after a unique specimen was collected in Itombwe Forest (hence the alternative name ‘Itombwe Nightjar’) in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in 1955. Its current status is obscure: a nocturnal forest species, it has not been seen since, but recorded calls from the area have, by a process of elimination of known species, been tentatively attributed to it, and these same calls have also been heard at several sites elsewhere in Central Africa – offering some hope that it continues to survive in the region. Its range could therefore be fairly extensive, but we are far from certain, and so cannot determine how threatened it might be by deforestation.

Siau Scops-Owl

The Siau Scops-Owl is only known from the small Indonesian island of Siau, north of Sulawesi. It is another species known only from the original, or type, specimen, this one collected in 1866. Several observers have searched for it without success (though not for more than a few days at a time), and little forest remains within its presumed range, in which habitat destruction has been extensive and is continuing. However, several examples have shown how scops-owls have survived undetected on tropical islands for many decades, sometimes adapting well to forest degradation, and there have been local reports on Siau that might relate to the bird, while neighbouring islets that could support an owl may never have been searched.

Himalayan Quail

Himalayan Quail has not been recorded with certainty since 1876, despite a number of searches. It was found in Uttarakhand, north-western India, and may yet survive in remoter areas of the lower or middle Himalayan range, as the searches to date have not been exhaustive. Like any quail it may be hard to find in its dense grassland habitat, from which it is reluctant to fly. Local reports have suggested it can be caught with the use of dogs, and indeed this seems to have been how it was originally found. This points to a likely reason for its decline and rarity, as dogs are often used to hunt birds. However, perhaps with the right communication and management, searches with dogs might become the means to refind the species, which may also have suffered from habitat degradation.

Jerdon’s Courser

Jerdon’s Courser was lost, found and lost again. This elegant, terrestrial species went missing for 86 years from 1900 until its rediscovery in the ‘scrub jungle’ of Andhra Pradesh State, central India – a considerable achievement for such a shy creature that is also nocturnal. Research and conservation efforts continued using all available methods, such as ‘tracking strips’ placed on the ground to collect evidence of the bird’s tracks, camera traps and tape transects. More sites were found, but the (few) sightings stopped in 2009 and no coursers have been seen or heard since, as unauthorised progress on a canal and additional habitat loss and degradation has reduced the available habitat. There is potential that it could occur elsewhere in India, and until all possibilities have been investigated we should not give up.

South Island Kokako

South Island Kokako, a striking and noisy species of a seemingly well-explored part of the world, might seem like a long shot for rediscovery. Like most other native New Zealand birds, it has suffered catastrophic declines caused by the destruction and fragmentation of its native forest habitat and the introduction of competitors, but predation by introduced rats, possums and stoats seems to be the biggest problem. While its North Island counterpart is scarce but readily findable, the last confirmed records of South Island Kokako were in 2007 and before that in 1967. Sadly, the reward offered since then for information confirming its survival cannot be claimed, but unconfirmed sightings up to 2016 give some hope and are the reason for the kokako’s inclusion here.

Dusky Tetraka

Dusky Tetraka is a small passerine that lives on or near the ground in the rainforests of Madagascar, where it has not been seen this century. Several species from that legendary island were until fairly recently in the ‘lost’ group, but have been found and are now regularly seen. This one is not, the most recent records being a sighting and sound recording followed by a mist net capture in the 1990s. There has been none since, despite there still being plentiful (albeit shrinking) habitat. It should be found again, and only then can we hope to understand the rarity of sightings and what has to be done to conserve it.

Why extinction matters

Does it matter whether Negros Fruit-dove, Santa Marta Sabrewing and others survive or not? Of course! Every extinction matters, and every species needs to be recognised not only in its own right, but also as a unique representative of the diversity of life in the place and habitat where it is found. “We also need to know the true extent and rate of extinctions in the era of unprecedented human domination now widely known as the Anthropocene,” says John C Mittermeier, Director of Threatened Species Outreach at the American Bird Conservancy. Negros Fruit-dove and the rest are lost to us now, but we hope not gone forever, and certainly not forgotten. We should do all in our power to find them again. Assuming we succeed, we must then use what we learn to conserve them and help the many other species sharing the extraordinary places where they live.

Also published in the BirdLife Magazine January-March 2022.

To subscribe, become a member of the World Bird Club.

Stay up to date

Sign up to receive the latest bird conservation news. You’ll also receive updates about our projects, science and other ways to get involved including fundraising.

Thank you for your support, we are committed to protecting your personal information and privacy. For more information on how we use your data, please see our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from emails at any time by using the link in the footer of any email from us.

Hulking past a seasonal waterhole – called trapaengs here in Cambodia – the shadowy form of a Giant Ibis probes soft mud with its immense, downcurved bill. Once this Critically Endangered waterbird has unearthed enough invertebrates, it will head deep into the forest to a treetop nest – one of 10 discovered last year at Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary. This vast site encompasses two Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) – including Lomphat, an ‘IBA in Danger’ where conservation action is now more urgent than ever.

Established in 1993, Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary carries remarkable significance for wildlife. Its 250,000 hectares form part of the Lower Mekong Dry Forests, one of the world’s 200 most important ecoregions. Roughly the size of the island of Mauritius, Lomphat intersperses dry deciduous woodland with evergreen forest, and seasonally flooded grassland with farmland. It hosts populations of not one but three Critically Endangered birds. As well as around 50 Giant Ibises – perhaps one sixth of the global population, which is almost entirely confined to Cambodia – there are internationally important numbers of White-shouldered Ibis and Red-headed Vulture.

Lomphat’s list of avian VIPs doesn’t stop there. Vorsak Bou, CEO of NatureLife Cambodia (BirdLife Partner) identifies a series of globally threatened birds that “depend on the Lomphat IBA, including using its waterholes for drinking and foraging during the dry season”. Families of the world’s tallest flying bird, Sarus Crane (Vulnerable), elegantly lope through the grasslands. Both Greater Adjutant (Endangered) and Lesser Adjutant (Vulnerable) stalk the channels. Under the forest canopy, the scintillating Green Peafowl (Endangered) strides purposefully. And then there are other globally threatened taxa, including Siamese Crocodile (Critically Endangered), Asian Elephant (Endangered) and two bovids, Banteng (Endangered) and Gaur (Vulnerable). At Lomphat, even the supporting cast are stars.

By James Lowen

Header Image: Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary is home to three Critically Endangered bird species, such as this Giant Ibis © Jonathan Eames

SANCTUARY UNDER PRESSURE

One might hope that such an unequivocally, empirically significant place for wildlife would be sacrosanct – safeguarded from humanity’s exploitative, even destructive urges. But conservation is rarely so simple. As many as 13,000 people, across 26 villages, live in or near this IBA. Like the wildlife, these local communities depend on Lomphat’s natural resources – from rain to grow rice, to rivers for water and fish-based protein. A bigger threat has come from a land-use policy known as economic land concessions, which grant companies rights to convert native forests into cash crops. “Concessions and land encroachment are the crucial pressures faced by Lomphat,” Bou explains. “They lead to habitat loss and are followed by hunting and snaring of birds and mammals.” From 2010 to 2018, an average of 3.3 per cent of Lomphat’s forests were felled every year.

Fortunately, Lomphat’s story is not all gloom, let alone doom. In 2013, the Cambodian government gave BirdLife International’s Cambodia Programme its blessing to strengthen protection of Lomphat. NatureLife Cambodia, Bou says, has now developed “a strategic investment plan, focusing on law enforcement and site management, biodiversity monitoring and research, community engagement and livelihood improvement, and sustainability”. These steps are already working. Rangers are patrolling key zones and employees of concession-holders are moving away from illegal hunting and trapping. Communities have been helped to use natural resources sustainably and financially incentivised to favour wildlife-friendly agriculture, including IBIS Rice, for which farmers receive a premium if they maintain environmental standards.

Lomphat’s tale of troubled importance is all too familiar. Since BirdLife developed the IBA concept during the 1980s, 13,500 IBAs have been identified worldwide, all also classified as Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) as they contribute to the global persistence of biodiversity. In 2013, BirdLife launched the ‘IBAs in Danger’ initiative to identify and showcase the most threatened IBAs.

Following assessments by BirdLife Partners, there are currently no fewer than 277 sites classified as IBAs in Danger. By 2020, the condition of over half the sites assessed was deemed to be ‘very unfavourable’ – an illustration of our attitude towards nature. The sites face many and varied problems – from pervasive agricultural encroachment on forests to infrastructural development at wetlands – which fundamentally boil down to tensions between the needs of people and those of wildlife.

“Concessions and land encroachment are the crucial pressures faced by Lomphat. They lead to habitat loss and are followed by hunting and snaring of birds and mammals.”Vorsak Bou, CEO of NatureLife Cambodia (BirdLife Partner)

BIGGER PROBLEM

These vital places, all in dire need of conservation action, are spread across 48 countries on six continents. Despite having already suffered conversion of 80 per cent of its coastal wetlands, Canada’s Fraser River Delta still supports over 1.7 million birds annually, with 30 species exceeding global or national criteria for designation as an IBA. James Casey of Birds Canada (BirdLife Partner) explains that even the remaining avian visitors are not safe, with a proposal for a new container port by the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority the “most immediate and highest priority threat”.

Infrastructure also imperils Portugal’s Tejo (or Tagus) Estuary, which lies adjacent to the national capital of Lisbon and hosts over 100,000 waterbirds, more than half comprising wintering Black-tailed Godwits (Near Threatened). Two million people live around this IBA in Danger, and a proposed new airport risks juxtaposing aircraft and bird flight paths – never a safe combination, for birds or people.

Argentina should shortly sign into law the creation of Ansenuza National Park, incorporating Mar Chiquita, South America’s largest salt lake, which is frequented by up to a million waterbirds. Formal protection may come in the nick of time for this IBA in Danger, which, says Laura Dodyk of Aves Argentinas (BirdLife in Argentina), is suffering “severe pressure from factors such as alteration of the hydrological regime, pollution, over-exploitation and consequent loss of biodiversity”.

In Australia, Bruny Island was identified as a KBA in Danger during 2017. The Tasmanian island episodically hosts large breeding populations of Swift Parrot (Critically Endangered) and is one of the last remaining refuges for Forty-spotted Pardalote (Endangered), but under current laws the prospect of logging its native forests remains. BirdLife Australia has been lobbying decision-makers to strengthen nature legislation, protect Swift Parrot breeding habitat and invest in the future job creation and economic benefits that intact forests can provide to local communities. Swift Parrots and Forty-spotted Pardalotes are threatened in other Australian KBAs too, so “Bruny alone will not save these species”, says Dean Ingwersen (BirdLife Australia). “But without Bruny we have no chance”.

GETTING WITH THE PROGRAMME

It is the BirdLife Secretariat, through its IBA Programme, that puts all this evolving information together to deliver a global perspective. And it does much more besides. Zoltan Waliczky (BirdLife’s Global IBA Programme Co-ordinator) explains that the Secretariat advocates for safeguarding IBAs in Danger at the international level, such as through the Ramsar Convention or at development banks.

The Secretariat also enlists the support of other international conservation organisations through the KBA Partnership and enhances BirdLife Partners’ national campaigns, including through direct engagement with decision-makers and by mobilising expertise to where it is most needed. “We also publish a ‘story map’,” Waliczky says, “that showcases how BirdLife Partners are actively addressing the most severe threats at IBAs in Danger.”

Lomphat itself is a case in point. Bou explains how BirdLife in Cambodia is addressing the most urgent pressures facing the IBA. Ahead of the 30th anniversary of the sanctuary’s formal designation next year, NatureLife’s ambition is impressively bold – but nothing less than Lomphat merits. Indeed, nothing less than Lomphat demands. Through structures known as ‘community protected area committees’, Bou says that NatureLife is “supporting and encouraging the local community to become involved in bird conservation, and in the protection and restoration of habitat”. One element involves incentivising local communities to manage the forest sustainably, in ways that not only help conserve key flagship species such as Giant Ibis but also, critically, enhance their own livelihoods. Bou envisages scaling up the IBIS Rice scheme and improving the efficiency of farmers’ resource use alongside “strengthening community-based ecotourism, offering small grants for community protected area management and conducting educational outreach”.